Joyce Music – Barber: Now Have I Fed and Eaten Up the Rose

- At February 06, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

If I can judge by last night [Schoeck] stands head and shoulders over Stravinsky and Antheil as composer for orchestra and voice anyhow. I did not know Keller wrote this kind of gruesome-satiric semi-pious verse but the effect of it on an audience is tremendous.

—James Joyce, Letter to Giorgio Joyce, 15 January 1935

“Now have I fed and eaten up the rose”

Song 1 from Three Songs, op. 45

(1972)

For voice and piano

(Moderato, James Joyce: after the German of Gottfried Keller)

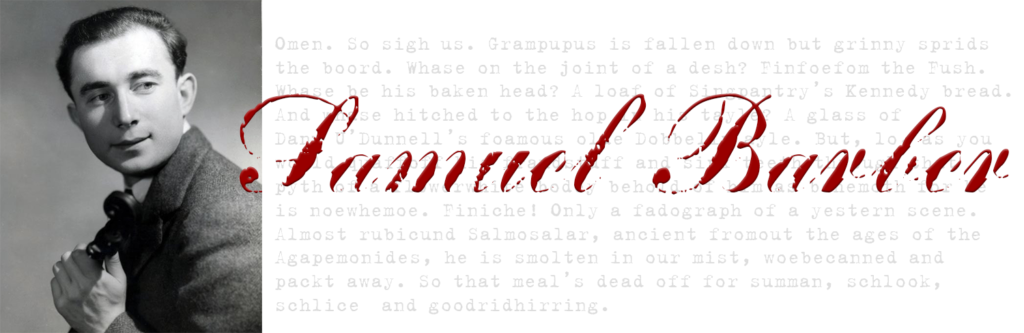

In 1935, James Joyce saw a performance of Othmar Schoeck’s Lebendig Begraben in Zurich. Scored for orchestra and basso profondo, the song cycle was based on a series of macabre poems written by Gottfried Keller in 1846 and revised in 1888. Usually translated as “Buried Alive,” the poems describe a man who awakes to find himself interred in a coffin. Joyce was so impressed by Keller’s “gruesome-satiric semi-pious verse” he sent a copy of Keller’s poems and Schoeck’s score to his son Giorgio.

Sebastian Knowles describes the poems in his essay, “Opus Posthumous,” published in Bronze by Gold: The Music of Joyce:

Through the fourteen poems of Lebendig Begraben Keller somehow sustains the gruesome conceit of a prematurely encoffined speaker alternating between frustrated attempts to escape, or at least to communicate with those above him in the present, and resigned elegies to a pastoral world that he can no longer revisit. Thus is neatly combined the alienation of the poet from the world he lives in, since the world is entirely envisioned in the mind while the body lies paralyzed, and the traditional nostalgia of the romantic poet for a lost natural world. But both the present alienation and the past emotion recollected in tranquility are given a novel edge in the hapless condition of the speaker, for the tranquility is now eternity, the pensiveness is now despair, and the couch upon which the poet lies is the bed of the grave.

Joyce translated Poem XIII of Keller’s ghoulish cycle into English. Called “Da hab’ ich gar die Rose aufgegessen,” or “Now have I fed and eaten up the rose,” the poem details the doomed man’s last supper—a flower from his own funeral corsage! Joyce’s translation appeared in Herbert Gorman’s 1939 biography, James Joyce, which is where Samuel Barber first came upon it. In 1972 while living in Spoleto, Barber decided to set the translation to music.

The early seventies were a profoundly unhappy time for Barber. His opera Antony and Cleopatra had flopped, his romantic relationship with Gian Carlo Menotti had ended, and he was forced to sell Capricorn, their beloved Mount Kisco home. Depressed and battling alcoholism, Barber expressed his emotions in Three Songs, opus 45. As Barber’s biographer Barbara Heyman writes:

Their metaphorical texts are particularly portentous, considering the composer’s anguished state of mind. The first and third song of the set suggest the act of completion: having “eaten the rose” is a symbol of the depletion of the source of creative energy; “Soon the glow / Of long hills on the skyline will be gone” seems symbolic of the eventuality of death, thus the completion of a life… The morbid text is intensified by obsessive repetitions in the piano part, where the unrelenting reiteration of a four-note motive introduced in the first two measures seems to gain momentum from the ornamented upbeat.

Responding to Keller’s ironic religious imagery, Barber frames the song as a hymn—a rather bleak hymn from the Church of Edgar Allan Poe, perhaps, but the religious overtones are hard to deny. Indeed, it’s easy to believe the song is purely spiritual until one listens to the grotesque lyrics! A torch passed from one artist in the last decade of his life to another, Joyce’s translation of this grave poem was among the last songs Barber published.

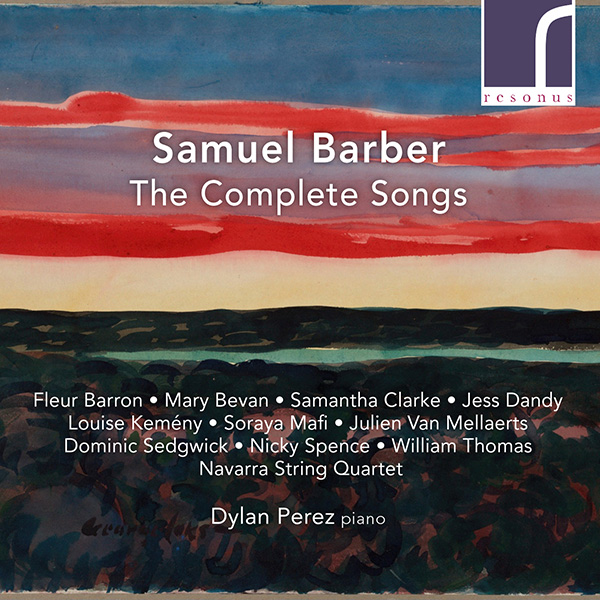

Liner Notes from Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs

By Dylan Perez

Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs

Resonus, 2022

Barber’s final published songs Three Songs, Op. 45, were written for Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, although illness and travel meant he did not perform the premiere, even though he adored them. The morbid text of the first song ‘Now have I fed and eaten up the rose’ is illuminated by a hymn-like piano accompaniment, marrying heaven and earth. The second song ‘A Green Lowland of Pianos’, which Barber found ‘funny’, fuses pianos and cows together with flourishes in the keyboard writing. ‘O boundless, boundless evening’ is expansive like the night unfurling before our eyes, comforting us into the darkness.

Liner Notes from Buried Alive

By Peter Laki

Buried Alive: Honegger, Schoeck, Mitropoulos

Bridge, 2020

Swiss composer Othmar Schoeck (1886-1957) is usually considered an arch-conservative whose most successful works were Lieder for voice and piano in the late Romantic tradition. Yet Lebendig begraben (“Buried Alive,” 1926), a monumental composition for baritone and orchestra, is a bold expressionist depiction of a horrible nightmare. It was described by critic Paul Griffiths as less a song cycle than a “monodrama.” (The work was originally intended for a basso profondo but a version for a higher baritone voice exists, which was famously recorded by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in 1962, and is recorded here by Michael Nagy.)

Surprisingly, the words of this nightmare did not come from a modernist poet but from Gottfried Keller (1819-90), a master of literary realism born in Zurich and known mainly for his novels. Keller produced most of his lyrical poetry during the earlier part of his career; Gedanken eines lebendig Begrabenen (“Thoughts of One Buried Alive”) was written in 1846.

In this cycle of fourteen poems, the absurd premise is developed with a sense of realism that makes it even more absurd. From his grave, the unfortunate protagonist hears the noises of the outside world as his entire life flashes before his eyes—memories of his first love, his first Christmas tree, a marksmen’s festival with song and a young girl from the mountains with a flower in her hair… Yet there is no escape from this living death, and the protagonist must resign himself to his fate, which he does with defiant pride. In a final heroic gesture, he lets go of his self and embraces the inevitable.

Schoeck’s music—forty minutes with no pauses between sections—follows this internal monologue with great dramatic power. In the vocal part, violent outbursts alternate with subdued recitations on a single note. The most expressive elements, however, are often in the orchestral parts. The piano, harp and organ produce a particularly intense emotional effect. In the last song, a wordless chorus of four mezzo-sopranos and four baritones, amplifies the ecstatic vision of eternity; however, the last word belongs to the soloist alone as he proclaims his spiritual triumph over his grim destiny.

Lebendig begraben made a deep impression on James Joyce when he heard the work at a concert in 1935. In a letter to his son and daughter-in-law, Joyce rated Schoeck “head and shoulders over Stravinsky and [George] Antheil as a composer for orchestra and voice anyhow.” The writer and the composer met in person at the time, and Joyce translated at least one of Keller’s poems into English. “Da hab’ ich gar die Rose aufgegessen” thus became “Now I have fed and eaten up the rose. [sic]” The translation was set to music by Samuel Barber in 1972—for Fischer-Dieskau, whose name had long been associated with the same poem in the original setting by Schoeck.

Texts

In 1846 Gottfried Keller published Gedanken eines Lebendig-Begrabenen, or “Thoughts of a Living Burial.” A cycle of nineteen poems, Poem XIII was “Da hab’ ice gar die Rose aufgegessen.”

Da hab’ ich gar die Rose aufgegessen (1846 version)

Da hab’ ich gar die Rose aufgegessen,

Die man mir in die starre Hand gegeben!

Daß ich noch einmal Rosen würde essen,

Ich hab’ es nie geahnt in meinem Leben.

Ich möcht’ nur wissen, ob es eine weiße,

Ob eine rothe Rose das gewesen?

Am letzten Blatt, das spielend ich zerreiße,

Möcht’ ich es fühlend mit den Fingern lesen.

Wie vielen Gärten voller Knospenprangen

Bin ich gedankenlos vorbeigezogen!

Voll Geigen hat der Himmel mir gehangen—

Nur fand ich nicht den rechten Fiedelbogen.

Blühn auch Rosen an des Himmels Bächen?—

Was kümmert’s mich? Noch will ich es nicht wissen!

Will erst noch dieser Erde Rosen brechen!

He! lasst mich los aus diesen Finsternissen!

Ich will nicht sterben! Jung sind meine Sehnen

Und rasch noch die Gelenke meiner Knochen;

Ahnt Niemand meine zornig-heisen Thränen?

Auf! Holla! schlechter Kasten, sei zerbrochen!

—Wie Felsen halten diese Bretterstücke,

Und seine Fuge weicht, wie ich mich dehne;

Erschöpft und keuchend lehn’ ich mich zurücke,

Die nassen Haare voller Hobelspäne.

Now I have entirely consumed the rose (Jean Kreiling translation )

Now I have entirely consumed the rose

Which someone gave me in my stiff hand!

That I would once again eat roses

I never in my life suspected.

I would only like to know if it was a white

Or a red rose?

At the last petal, which I easily tear up,

I would like to read it, feeling it with my fingers.

How many gardens full of displays of buds

Have I thoughtlessly passed!

Full of violins heaven has hung for me—

But I did not find the right bow.

Do roses also bloom well at heaven’s streams?—

What troubles me? Still I do not want to know!

First I want to break the roses of this earth!

Ah! let me out of this darkness!

I will not die! My sinews are young

And the joints of my bones are still quick;

Does no one believe my hot, angry tears?

Away! Halloo! evil crate, be shattered!

Like rocks these pieces of boards contain [me],

And their joints soften, as I extend myself;

Exhausted and gasping, I lean back,

My wet hair full of shavings.

In 1888 Keller revised his subterranean cycle, reducing the number of poems to fourteen and shortening its title to Lebendig Begraben. Edited from six stanzas to two, “Da hab’ ice gar die Rose aufgegessen” was renumbered as Poem VIII. This is the version that Othmar Schoeck set to music in 1926.

Da hab’ ich gar die Rose aufgegessen (1888 version)

Da hab’ ich gar die Rose aufgegessen

Da hab’ ich gar die Rose aufgegessen,

Die sie mir in die starre Hand gegeben!

Daß ich noch einmal würde Rosen essen,

Hätt nimmer ich geglaubt in meinem Leben!

Ich möcht’ nur wissen, ob es eine rote,

Ob eine weiße Rose das gewesen?

Gib täglich uns, o Herr! von deinem Brote,

Und wenn du willst, erlös’ uns von dem Bösen!

In 1935, James Joyce translated the poem into English. His translation first appeared in Herbert S. Gorman’s biography, James Joyce. When Samuel Barber set it to music in 1972, he changed “in this dark” to “in the darkness.”

Now have I fed and eaten up the rose (James Joyce translation)

Now have I fed and eaten up the rose

Which then she laid within my stiffcold hand.

That I should ever feed upon a rose

I never had believed in liveman’s land.

Only I wonder was it white or red

The flower that in this dark my food has been.

Give us, and if Thou give, thy daily bread,

Deliver us from evil, Lord. Amen.

Recordings: “Now have I fed and eaten up the rose”

Complete Songs

There are three recordings of Samuel Barber’s complete songs available on compact disc.

|

|

Barber: The Complete Songs (1994)

Piano: John Browning

Vocalists: Cheryl Studer, Thomas Hampson

CD: Complete Songs of Samuel Barber: Secrets of the Old. Deutsche Grammophon 435 867-2 (1994)

Reissue CD: Barber: The Complete Songs. Deutsche Grammophon 459 506-2 (2002)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: Youtube [Album Playlist | Now have I fed and eaten up the rose]

Recorded in 1991-1992 and released on Deutsche Grammophon in 1994, this venerable 2-CD set has never been out of print, a mandatory purchase for fans of Samuel Barber’s elegantly-crafted art songs. It features the soprano Cheryl Studer and the baritone Thomas Hampson, with John Browning on piano and the Emerson String Quartet backing Dover Beach. Having boasted several album covers and titles—including Secrets of the Old—this set continues to shine thirty years later. The liner notes are sparse and the production favors contemporary notions of close-miking and reverb, but the performances are stellar, all musicians in top form. John Browning was Barber’s own choice to première his Pulitzer-Prize winning Piano Concerto, so he’s as definitive a Barber interpreter as the twentieth century has to offer. Cheryl Studer is magnificent. While some operatic sopranos might be tempted to showy displays, Studer allows the lyrics to dictate her delivery, and she touches each word with an appropriate amount of grace, irony, impishness, and sorrow. (Her Nuvoletta is a delight!) And Thomas Hampson’s silky baritone is always a pleasure to hear. Although his voice is darker than the tenor Joyce had in mind, he brings a richness to each of his selections, especially the dramatic clangor of “I hear an army.” A collection that’s stood the test of time, Secrets of the Old—or whatever it’s being called at the moment!—belongs in the library of every classical music fan.

Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs (2022)

Piano: Dylan Perez

Vocalists: Fluer Barron, Jess Dandy, Louise Kemény, Soraya Mafi, Dominic Sedgwick, Nicky Spence, & others

CD: Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs. Resonus RES10301 (2022)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Now I have fed and eaten up the rose]

Since 1994, fans of Samuel Barber had only the Deutsche Grammophon Secrets of the Old set to represent Barber’s complete songs. As good as that set is, thirty years of the same interpretations can become overfamiliar. Fortunately, this remarkable 2-CD set by Resonus has arrived to freshen things up. Interested visitors are directed to the Brazen Head review of Samuel Barber: The Complete Songs. Here’s an excerpted passage describing the set’s “Now I have fed and eaten up the rose”:

A metaphor for artistic exile and creative decay, “Rose” is one of the last songs Barber wrote. It’s sung by Jess Dandy, a young contralto with a strikingly powerful voice. Sensitive to the poem’s religious imagery, Dandy invests the ironic hymn with liturgical plangency, her resonant voice transforming the confines of her coffin into the walls of a cathedral. I’ve heard over a dozen versions of “Rose,” from Thomas Hampson’s resigned sighing to keening recitals on YouTube. This version is the best: Dandy understands the essential weirdness of the song.

Samuel Barber: Complete Songs (2023)

Piano: Filippo Farinelli

Vocalists: Leilah Dione Ezra, Elisabetta Lombardi, Mauro Borgioni

CD: Brilliant Classics 96514 (2023)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist] | Now I have fed and eaten up the rose]

Following close on the heels of the Resonus set is this wonderful release by Brilliant Classics, boasting no less than 65 of Barber’s songs—all the standard pieces from the famous Browning collection, plus many more early and lesser-known works. Italian baritone Mauro Borgioni’s reading is thick and lugubrious—though not so resigned to death he forgets to roll his r’s and include the odd dramatic flourish! Nevertheless, his final “Amen” is perfect, touched with an irony lost on many interpreters. Visitors interested in reading more are directed to the Brazen Head review of this collection.

Selected Songs

“Now have I fed and eaten up the rose” is available on the following collections:

|

|

Barber: Three Songs op. 45 (1982)

Piano: David Garvey

Mezzo: Glenda Maurice

LP: Britten/Barber. Etcetera ETC 1002 (1982)

CD: Samuel Barber/Benjamin Britten. Globe GLO 5017 (1989)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Now have I fed and eaten up the rose]

Oh it has a terrible cover. And Garvey’s piano never rises above the level of “solid accompanist.” But the late American singer Glenda Maurice has her following, and her bright mezzo-soprano is certainly expressive. These are dramatic readings; perhaps overcooked but never melting into gooey sentimentality. Maurice sings two songs from Three Songs op. 10, a flowery “Sleep Now” and a melodramatic “I hear an army.” While it doesn’t approach the intensity of Gweneth-Ann Jeffers’ recording thirty years later, Maurice’s final “Why have you left me alone” conveys genuine anguish. The album also features the entirety of Three Songs, op. 45. Maurice drenches “Now have I fed and eaten up the rose” with despair, her final “Amen” a resigned passing unto death.

|

|

Samuel Barber: Three Songs op. 45 (1994)

Piano: Roger Vignoles

Baritone: Sir Thomas Allen

CD: Barber: Dover Beach. Virgin Classics 7243 5 45033 2 0 (1994)

Reissue CD: American Classics: Samuel Barber. EMI Classics 50999 6 95232 2 9 (2009)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Amazon | Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Now have I fed and eaten up the rose]

This collection was originally issued on CD by Virgin Classics Digital. It was reissued in 2009 by EMI with a different name, a new cover, and five additional tracks: the songs of Despite and Still, op. 41, with Eric Cutler singing tenor and Bradley Moore on piano. For the interests of Joyce enthusiasts, both versions contain Three Songs op. 10 and “Now have I fed and eaten up the rose,” but only the 2009 EMI release features “Solitary Hotel.” The Robert Vignoles/Thomas Allen songs were recorded at St. George’s Church in Bristol in April 1993. Allen has a strong, resonant baritone and Vignoles is a capable accompanist, but there’s nothing to recommend this disc over the superior DG set released that same year. There’s also a hollowness to the sound quality that one associates with budget releases. Despite and Still fares better than the earlier recordings, but it’s safe to give this collection a pass.

Barber: Three Songs op. 45 (2002)

Piano: Tom McGrath

Baritone: Ernst Buscagne

CD: Lieder. Genuin GMP020202 (2002)

Purchase: CD [Presto Music], Digital [Amazon | Presto Music]

This now-deleted CD contains a mellifluous and somewhat ornate reading of “Now I have fed and eaten up the rose” by South African baritone Ernst Buscagne. It was released by the German label Genuin Classics, who seem to have a thing for unfortunate album covers.

Barber: Three Songs op. 45 (2010)

Piano: Jerad Mosbey

Baritone: Joshua Hopkins

CD: Let Beauty Awake. Atma Classique ACD22615 (2010)

Purchase: CD [Amazon | Presto Music], Digital [Presto Music]

Canadian baritone Joshua Hopkins sings Three Songs, op. 45 on this collection “united by a strong sense of place and the underlying presence of nature.” While the quality of the recording is excellent, Hopkins delivers “Rose” a bit too floridly for my taste, his voice quivering with vibrato above Mosbey’s ghostly piano. (For what it’s worth, his reading of “A Green Lowland of Pianos” is far more serious than the whimsical lyrics can support, but “O Boundless, Boundless Evening” sounds quite lovely.) Also, the CD seems to be deleted—for those wanting a physical copy, Presto Music has them much more reasonably priced than Amazon Marketplace.

Barber: Three Songs op. 45 (2018)

Piano: Danny Driver

Baritone: Christian Immler

CD: Swan Songs. Avi Music AVI8553402 (2018)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube [Album Playlist | Now have I fed and eaten up the rose]

German baritone Christian Immler offers a melodic interpretation of “Rose” tinged with sorrow and shimmering with quiet regret. His reading reveals a welcome amount of restraint, eschewing melodrama for an affecting sense of self-awareness—“Only I wonder was it white or red” is perfectly timed, a self-pitying moan that collapses into bemused black humor. The result is pure magic. Immler’s partner in casting this spell is the sublime English pianist Danny Driver. He opens “Rose” like he’s discovering the notes for himself, continues to brush Immler’s lament with subtle colorations, then quietly ushers the song to its spectral conclusion. The entire album is highly recommended!

Online Video

The following excerpts and live performances are available on YouTube. A YouTube search reveals many more performances of this song, which has apparently become quite popular at senior recitals!

Barber: Three Songs, op. 45

Baritone: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Piano: Charles Wadsworth

Fischer-Dieskau premieres Barber’s Three Songs, op. 45 at Lincoln Center, 30 April 1974.

Barber: “Now have I fed and eaten up the rose”

Tenor: Ángel Rodríguez Rivero, Piano: Laurence Verna

Recorded at El Jardín de Belagua, 28 May 2010.

Barber: “Now have I fed and eaten up the rose”

Soprano: Emily Šaras, Piano: Šarūnas Meškys

From “An evening of American music” in Didžioji Aula, Lithuania. 26 June 2012.

Barber: Three Songs, op. 45

Soprano: Bethany Worrell, Piano: Sarah Thune

Filmed during Worrell’s DMA Dissertation Recital at the University of Michigan, 1 October 2023.

Recordings: Othmar Schoeck’s Lebendig Begraben

|

|

|

Schoeck: Lebendig Begraben (1962)

Conductor: Fritz Rieger

Musicians: Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

Bass: Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

LP: Schoeck: Lebendig Begraben. Deutsche Grammophon LPM 18 821 (1962)

CD: Pfitzner: Von Deutscher Seele; Schoeck: Lebendig Begraben. Deutsche Grammophon 437 033-2 (1992)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: Youtube

There are a many versions of this 1962 recording floating around, including a now-deleted CD from Claves. As often noted in reviews, Fischer-Dieskau takes liberties with the score, and sings in a higher register than one might expect. The modern DG set pairs Lebendig Begraben with Hans Pfitzner’s Von Deutscher Seele.

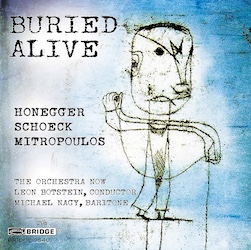

Schoeck: Lebendig Begraben (2020)

Conductor: Leon Botstein

Musicians: The Orchestra Now

Baritone: Michael Nagy

CD: Buried Alive. Bridge 9540 (2020)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: Youtube [Album Playlist]

Although Michael Nagy is technically a baritone, his voice here is deliciously sepulchral—a true “bass barreltone” emerging straight from the grave. A fine review in Classics Today discusses the interpretive differences between Nagy and Fischer-Dieskau. The Bridge disc also includes lesser works by Arthur Honegger and Dmitri Mitropoulos.

Online Video

The following excerpts and live performances are available on YouTube.

Lebendig Begraben

Baritone: Oskar McCarthy, Piano: Rob Keeley

A version for voice and piano, performed at the Chapel of Brompton Cemetery for the “London Month of the Dead” in 2015.

Additional Information

Gottfried Keller Wikipedia Page

Wikipedia has a small page on the poet Gottfried Keller.

Otmar Schoeck Wikipedia Page

The Swiss composer who originally set Keller’s poetry.

Bronze by Gold: The Music of Joyce

Published by Garland in 1999, this collection of essays features Sebastian D.G. Knowles’ “Opus Posthumous: James Joyce, Gottfried Keller, Othmar Schoeck, and Samuel Barber.” And extended treatment of “Now have I fed and eaten up the rose,” the essay places Keller’s poem in context with Joyce’s oeuvre, particularly Finnegans Wake.

Paywall:

“A Note on James Joyce, Gottfried Keller, and Music”

Jean L. Kreiling. James Joyce Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Spring, 1988). Kreiling discusses the history of Keller’s poem and Joyce’s translation. She erroneously ascribes Keller’s 1888 revision to Othmar Schoeck; a mistake thoroughly explained by Sebastian Knowles in “Opus Posthumous.”

Samuel Barber: Other Joyce-Related Works

Samuel Barber Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Samuel Barber profile.

Songs from Chamber Music (1935-1937)

These six songs are settings of poems from Chamber Music.

Nuvoletta (1947)

A playful song with lyrics adapted from Finnegans Wake.

“Solitary Hotel” (1969)

From Despite & Still, this song has lyrics adapted from Ulysses.

Fadograph of a Yestern Scene (1971)

A short instrumental inspired from a line in Finnegans Wake.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 30 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com