Joyce Music – Albert: TreeStone

- At January 24, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

I used “Finnegans Wake” more or less as a reference work, the way other composers might use the Bible, finding certain passages in it that lend to musical treatment of a direct sort, such as actual song settings, or a more indirect sort, such as my symphony. The symphony in not really a programmatic work in the accepted sense: it represents my response to a Joycean stimulus, but that response is not the type that involves an attempt at direct imagery.

—Stephen Albert on “Symphony RiverRun”

TreeStone

(1983)

Part I

1. I am Leafy Speafing (12:39)

2. A Grand Funferall (4:21)

3. Sea Birds (3:16)

Part II

4. Tristopher Tristian (1:44)

5. Fallen Griefs (5:17)

6. Anna Livia Plurabelle (10:47)

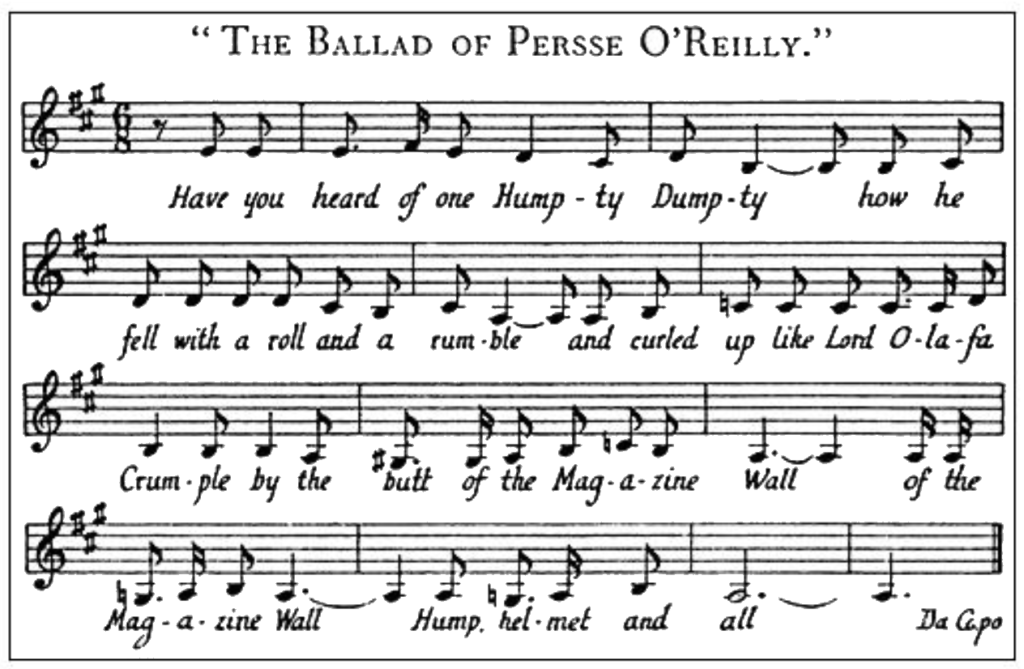

TreeStone has its origins in Albert’s fascination with Finnegans Wake; an interest that began in 1978 with his song cycle, To Wake the Dead. This earlier piece provided material for two additional Wake-related projects completed around the same time: TreeStone, song cycle scored for soprano, tenor and chamber orchestra; and Symphony RiverRun, posthumously re-designated Symphony No. 1, “RiverRun.” While Symphony RiverRun brings the River Liffey to life—Joyce’s allmaziful Anna Livia Plurabelle—TreeStone is a “retaling” of the Tristan/Iseult legend by the Wake’s two washerwomen. Both compositions share musical material with To Wake the Dead, the most prominent being the distinctive melody that Joyce inscribed into Finnegans Wake as sheet music: “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly,” itself an adaptation of an old Irish tune called “Mush Mush.”

Liner Notes from the 1989 Delos CD

Liner notes written by Stephen C. Smith and Stephen Albert:

The music of Stephen Albert is a fascinatingly complex world of allusion, dramatic contrast and metaphor. Precise meaning may be elusive, but communication between artist and audience is achieved through the accumulation of sounds and images into a greater emotional whole.

This fascination with paradox and nuance of feeling characterizes much of Albert’s work. It is not surprising, then, that the composer has often drawn from the evocative prose of James Joyce for inspiration, from the song cycle To Wake the Dead and the Pulitzer Prize-winning symphony RiverRun (both inspired by Finnegans Wake) and the aria Flower of the Mountain (on texts from Ulysses) to the present song cycle, TreeStone.

TreeStone, completed in 1984[sic], marked Stephen Albert’s third setting of James Joyce. The composer considers the song cycle a vocal counterpart to his symphony RiverRun, with which it was composed simultaneously, and with which it shares its basic musical material. (In describing the relationship between the two works, Mr. Albert explains that they “are adaptations of each other.”) Scored for flute/piccolo/alto flute, clarinet/bass clarinet, trumpet, horn, percussion, harp, piano and strings, TreeStone reinforces the free-flowing ideas of Finnegans Wake (mankind’s fall, the cyclic nature of life, the conflict between life’s tragic and comic elements) through subtly repeated motives, harmonic relationships and coloristic ideas. Observes Mr. Albert:

“The myth of Tristan is one of the more persistent yet elusive themes in Finnegans Wake. It hovers ghostlike throughout the novel, never wholly perceived but nearly always felt. The story of Tristan is communicated in coded fragments by different persons, challenging our reason and powers of intuition. Our associative memory is forced to the edge, deciphering and piecing together Joyce’s abbreviated, irreverent and often deranged version of the tale.

I had already set portions of Finnegans Wake in an early song cycle (To Wake the Dead). After putting the book aside for a couple of years, I began skimming through it again during the fall of 1982 and was intrigued by the recurring allusions to the Tristan and Iseult legend. After a few days of jotting down isolated paragraphs, sentences and phrases that seemed associated with their story, a fairly coherent text emerged that centered Tristan and Iseult in a cluster of related themes and images. The resulting text was cast in seven movements, forming in themselves a musical whole.

The first song, “I am Leafy Speafing,” is the voice of the River Liffey as it flows through Dublin at dawn. The movement opens with an instrumental prologue (“rain music”) followed by the soprano’s entrance as the “feminine” aspect of the river’s voice. She reminds her sister and companion, Dublin, how much joy and grief they’ve shared as silent witnesses to mankind’s history.

The second song, “A Grand Funferall,” comprises a dirge-like march, a children’s music-box ditty and rowdy pub music commingled in a single movement. We are really at a wake—Tristan and Iseult’s funeral. It is not outwardly a particularly sad or solemn occasion, but there is a slightly demonic streak present—an undercurrent of icy fear among the mourners. They try to dignify the event with a funeral march but cannot really escape their own private fears of parting and disconnection.

“Sea Birds,” the third song, returns in time to a bird’s-eye view of Tristan and Iseult’s first kiss aboard ship, but it is also the instant of their first curse: “The birds of the sea they trolled out right bold when they smacked the big kuss of Tristan with Isolde…”

In “Tristopher Tristian” and “Fallen Griefs,” the fourth and fifth songs, two washer-women banter about a family scandal concerning “cousins” in the remote part—in fact, the “cousins” are Tristan, and English soldier and Iseult, an Irish Princess.

The text of the final song is a small portion of the most familiar section of Finnegans Wake and is entitled “Anna Livia Plurabelle.” It is both the “masculine” aspect of the river’s voice as well as the interior closing monologue of the older, more dominant washer-woman. Shee feels darkness coming over the river and, perhaps, over her own life as well. Tired of washing, tired of talking, tired of remembering, she “…could near to faint away. Into the deeps. I saw home slowly now by my own way, moy valley way. Thinking always if I go all goes.”

Life along the river at dusk is becoming more and more intense and vivid, but her senses are fading. She glances across to the river’s opposite bank and sees her younger companion turning to stone. Her own arms have been transfigured into the limbs of a tree as her body is taking root. She is surrounded by sounds in the night and of the river. Both women have become transformed into more enduring parts of nature, one a tree, the other stone, as the river flows between them. The river will always be a source of their own connection, but it will also divide them. The Liffey now makes its way past Dublin and rushes into the sea as the night falls.”

Liner Notes from the 2012 Naxos CD

Liner notes written by Paul Schiavo:

During the 1970s and 1980s, two important trends emerged in American music as alternatives to what struck many observers as the arcane and hermetic high-modernism that had come to dominate composition after the middle of the twentieth century. The first of these new developments was the “minimalism” pioneered by Steve Reich, Philip Glass and others. The second was what came to be called “The New Romanticism.”

The latter tendency was, in some ways, the more surprising. In reclaiming not only certain features of traditional harmony but the dramatic rhetoric of nineteenth-century composition, the practitioners of “The New Romanticism” explicitly rejected a central tenet of modernism, its revolt against the musical past. In particular, these neo-Romantic composers sought to reclaim for music a degree of emotional expression they felt had been sacrificed by their high-Modernist predecessors.

Stephen Albert was perhaps the most accomplished pioneer of “The New Romanticism.” A native of New York, Albert began composing during his adolescence under the tutelage of Elie Siegmeister. He subsequently studied at the Eastman School of Music, the Philadelphia Academy of Music and the University of Pennsylvania. He also spent time in Stockholm, where he worked with Karl-Birger Blomdahl. Albert’s music quickly gained recognition, earning the composer commissions from the New York Philharmonic, the Chicago Symphony, The Philadelphia Orchestra and other major ensembles, an appointment as Composer in Residence with the Seattle Symphony Orchestra and a faculty post at The Juilliard School, and a series of impressive awards, most notably the 1985 Pulitzer Prize for music.

Albert produced more than a dozen orchestral compositions, as well as works for smaller ensembles and for voices. This impressive body of work undoubtedly would have grown in size and scope had the composer lived to develop it. Tragically, Albert died in an automobile accident in December 1992, at age 51.

Stephen Albert repeatedly drew inspiration from the writing of James Joyce. Among his compositions based on Joyce’s works are the cantata Distant Hills, with texts from Ulysses; the song cycle To Wake the Dead and the Pulitzer Prize-winning Symphony RiverRun, both prompted by Finnegans Wake; and TreeStone, also written as a response to Joyce’s final novel. Albert composed the latter work in 1983, concurrently with Symphony RiverRun. The two pieces are related not only in their Joycean inspiration but through shared musical material. Indeed, Albert described them as “adaptations of each other.”

Scored for soprano and tenor accompanied by a small orchestra, TreeStone treats Joyce’s gloss on the legend of Tristan and Iseult, a recurring motif in Finnegans Wake. The tale of the ill-fated lovers “hovers ghost-like throughout the novel,” Albert observed, “never wholly perceived but nearly always felt.” Joyce, the composer continues, renders “an abbreviated, irreverent and often deranged version” of the medieval romance, “communicated in coded fragments…challenging our reason and powers of intuition.”

Albert prefaces the first of the six songs that comprise TreeStone with an instrumental prologue. Here a shimmering texture of metal percussion, high-pitched pizzicato and isolated woodwind sounds create an atmospheric “rain music.” A wistful clarinet arabesque serves as a transition to the song “I am Leafy Speafing,” in which the soprano presents the voice of the Liffey River flowing through Dublin. In Joyce’s characteristically allusive language, she sings to the city, calling forth memories they share. Albert’s orchestral setting develops both the “rain music” and the clarinet arabesque in a movement that is as freely associative as its text.

“A Grand Funferall,” the second song, combines somber and antic music to create an air of raucous surrealism. The scene is a wake for the deceased Tristan and Iseult, but a truncated funeral dirge and fragments of Latin liturgy given out by the tenor are overwhelmed by a children’s ditty, a bit of parlor song and generally excessive exuberance.

The third song, “Sea Birds,” brings a marked change of tone. Its text recalls the ocean voyage during which Tristan and Iseult succumbed to their fatal passion, imagining the lovers’ first kiss as seen by birds flying over their ship. The first sounds evoke the lonely vessel on the water. The more animated music that follows suggests the fluttering and swooping of the titular birds.

The next two songs, “Tristopher Tristan” and “Fallen Griefs,” also view the legendary lovers from an unusual perspective. Their texts are from a chapter of Finnegans Wake in which two washerwomen stand on opposite banks of the Liffey, gossiping as they launder. Their discourse, which flows as freely as the river between them, touches on a scandalous liaison of young cousins, these being Tristan and Iseult. In the first song, restless rhythms intimate the eager gossip of the women. The ensuing song, “Fallen Griefs,” is more sober, touching on the sorrows of she who, Joyce wrote, “wove a garland for her hair…of fallen griefs of weeping willow.”

The final song takes its text from the most famous portion of Finnegans Wake, a long passage known as “Anna Livia Plurabelle.” As darkness descends over the river, the elder washerwomen grow weary. One complains, “I feel as old as yonder elm.” The other feeling as “heavy as yonder stone.” Slowly, they become that which they have named, the first transformed into a tree, her companion into a stone. Tree and stone, TreeStone: a symbol of eternity and enduring nature, which Albert intimates poetically in the final measures of the piece.

Recordings

|

|

Albert: TreeStone (1989)

Conductor: Gerard Schwarz

Musicians: New York Chamber Symphony

Soprano: Lucy Shelton, Tenor: David Gordon

CD: Violin Concerto (In Concordiam) & Treestone. Delos DE 3059 (1989)

CD: In Concordiam & Treestone. Naxos 8.559708 (2012)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: Naxos | YouTube [Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4]

There is one commercial recording of TreeStone, recorded at RCA Studios in New York on 15 May 1989. It was paired with Albert’s 1986 violin concerto, “In Concordiam” and released on CD by Delos in 1989. In 2012, Naxos reissued the album with a different cover.

Additional Information

“When a Composer Breaks the Cocoon”

Christian Science Monitor, 6 June 1984. David Owens dislikes To Wake the Dead, but offers praise for TreeStone.

Stephen Albert “Overtones” Interview

Overtones, 1988. A very engaging and informative interview with Stephen Albert, who discusses his relationship to James Joyce, his compositional process, and his thoughts on modern music.

Stephen Albert Interview with Bruce Duffie

WNIB, 9 December 1990. The transcript of a telephone interview conducted with Stephen Albert.

Stephen Albert: Other Joyce-Related Works

Stephen Albert Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Stephen Albert profile.

To Wake the Dead (1978)

This remarkable song cycle is subtitled, “Six Sentimental Songs and an Interlude after Finnegans Wake.”

Symphony RiverRun (1983)

The gloriously dramatic Symphony RiverRun expands on Albert’s previous Wake-inspired material. It won the 1985 Pulitzer Prize in music.

Flower of the Mountain/Sun’s Heat/Distant Hills (1985-1989)

Flower of the Mountain is based on Molly’s soliloquy in Ulysses. In 1989 Albert paired it with another Ulysses-inspired song, Sun’s Heat. Together they form a two-movement piece called Distant Hills.

Ecce Puer (1992)

A setting of Joyce’s final poem for soprano.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 16 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com