Joyce Music – Albert: Symphony RiverRun

- At June 21, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

I used “Finnegans Wake” more or less as a reference work, the way other composers might use the Bible, finding certain passages in it that lend to musical treatment of a direct sort, such as actual song settings, or a more indirect sort, such as my symphony. The symphony in not really a programmatic work in the accepted sense: it represents my response to a Joycean stimulus, but that response is not the type that involves an attempt at direct imagery.

—Stephen Albert on “Symphony RiverRun”

Symphony RiverRun

(1983)

I. Rain Music

II. Leafy Speafing

III. Beside the Rivering Waters

IV. RiversEnd

Looking back at the second half of the twentieth century, one does not find an abundance of notable symphonies. There’s Shostakovich of course, towering above the landscape; Walter Piston, more praised than loved; and commendable entries from Hans Werner Henze, Charles Wuorinen, Einojuhani Rautavaara, and Christopher Rouse. But unless your name was Alan Hovhaness—who managed to compose 70 of the damn things before his death in 2000—it’s clear that symphonic form was slipping out of vogue. Neither serialism nor aleatory music were much interested in symphonic structure, and Berio’s brilliant Sinfonia (1969) seemed the final word in postmodern irony. The first decade of minimalism produced numerous lengthy works, but these tended to be exhaustive studies of technique or endurance. Henryk Górecki’s Symphony No. 3 of 1976 didn’t capture the public’s imagination until the celebrated 1991 recording, and Philip Glass wouldn’t produce a symphony until 1992, his wonderful “Low” symphony based on themes by David Bowie and Brian Eno.

For these reasons, naming Stephen Albert’s Symphony RiverRun (1983) as one of the best symphonies of the late twentieth century feels like clearing a low bar; but Albert’s inspired tribute to James Joyce is a worthy inclusion to a tradition that runs from Beethoven to Mahler, through Sibelius to Shostakovich. The Pulitzer Prize committee agreed, and Symphony RiverRun was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Music in 1985.

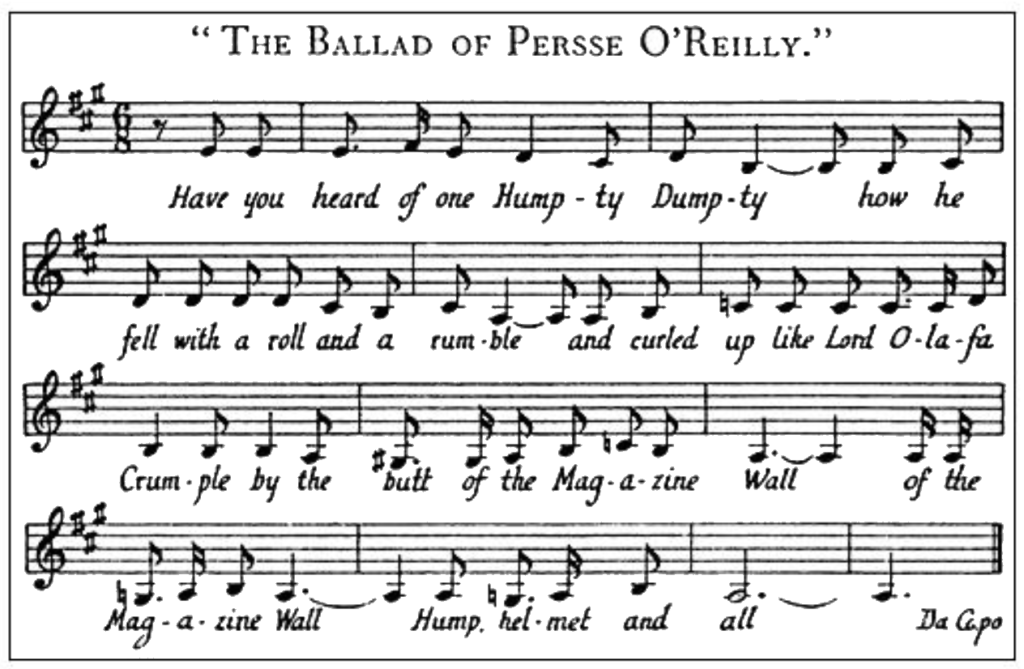

The symphony has its origins in Albert’s fascination with Finnegans Wake; an interest that began in 1978 with his song cycle, To Wake the Dead. This earlier piece provided material for two additional Wake-related projects completed around the same time: a second song cycle called TreeStone, and Symphony RiverRun, posthumously re-designated Symphony No. 1, “RiverRun.” While TreeStone is a “retaling” of the Tristan/Iseult legend by the Wake’s two washerwomen, Symphony RiverRun brings the River Liffey to life—Joyce’s allmaziful Anna Livia Plurabelle. Both compositions share musical material with To Wake the Dead, the most prominent being the distinctive melody that Joyce inscribed into Finnegans Wake as sheet music: “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly,” itself an adaptation of an old Irish tune called “Mush Mush.”

RiverRun opens boldly, brashly, the first notes of Beethoven’s Pathétique transformed into a surging fanfare as dramatic as the beginning of Strauss’ Elektra. We are immediately plunged into Albert’s lush soundscape. Entitled “Rain Music,” according to Albert the movement “is meant to convey the origins of a river,” and evokes showers of raindrops, peals of thunder, and the rolling rhythms of water in motion. The movement quickly gathers momentum, driven by a pumping figure on the horns and a swirling undercurrent of strings. Fragmentary themes tumble to the surface, flicker briefly in the foreground, and dissolve back in the flow. In the same way that Joyce used initials such as HCE and ALP to track the character transformations of Finnegans Wake, these themes will reappear throughout the symphony, often shifted or disguised—such as the conclusion of the movement, in which the opening fanfare returns in reverse order, its drawn-out chords enmeshed in a clamor of bells.

The second movement is called “Leafy Speafing,” and shares material with the TreeStone song of the same name. This movement strips the orchestra down to chamber size, unfolding its languid themes across a series of solos, duets, and trios. It’s gorgeous music, mysterious and longing, and reveals Albert’s considerable talent for finding beauty in unresolved tensions and offbeat colorations. Churning strings and tumbling piano push the movement towards a dramatic conclusion: seven minutes in, the horns announce the “Voice of the River.” As majestic waves of sound billow from the strings and brass, one can hear echoes of Wagner’s Rheinmusik, transforming the Liffey into all rivers: “They did well to rechristen her Pluhurabelle. O loreley! What a loddon lodes! Heigh ho!” (FW 201.35-36.)

Wagner, Strauss, Beethoven—these comparisons are not to suggest that Albert’s music is uninspired or blindly derivative. While RiverRun is often cited as an important work of “New Romanticism,” Albert himself disliked that label, claiming that Romantic music never really went out of style, but continued to evolve outside the doors of academia. As Joyce did with the work of Homer and Vico, Albert acknowledges what came before, then transmutes existing forms into something new and personal. His music may be Romantic in its tonal sensibilities, but it remains thoroughly modern, unafraid of dissonance and boldly seeking new textures and colors.

Nowhere is this more evident than the third movement, “Beside the Rivering Waters.” Combining march and scherzo, the movement recalls Ives and Berio in its aggressive whirlwind of clashing styles. In the way Berio riffed on Mahler in Sinfonia, here Albert plays with Joyce’s melody, “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly,” notated to sound “like a children’s music box.” The lilting tune is introduced by a rippling fanfare on horns, then undergoes a series of dizzying variations across a fractured orchestra: tossed merrily from the violins, pounded melodramatically on a parlor piano, twittered on besotted piccolos. Intermittently, the march intrudes to bust up the party. Intended to evoke a “boozy wake,” at times it feels a bit more sinister, like a drunken fragment of Shostakovich’s Leningrad.

After the raucous wake fades in the distance—leaving behind, as Albert suggested in an interview, “the inescapable moment of death itself”—the fourth movement, “RiversEnd,” begins by recalling the “Voice of the River.” As the sun sets and the river flows seaward, the music grows tentative and diffuse. Previous themes and rhythms return; now distorted, weary, ready to take their rest. Every so often the horns swell to a crescendo, the “Voice of the River” overflowing the banks to submerge all returning tributaries. As the final crescendo fades into silence, an enigmatic cascade of notes twinkles from the glockenspiel like a falling star.

Liner Notes from the Delos CD

Liner notes written by Richard Freed:

Stephen Albert was born in New York on February 6, 1941.

From the beginning, Albert has pursued a truly independent course, not as a rebel or an “outsider,” but simply as a creative thinker who developed a personal outlook without regard for what may have been “in” or “out” in musical fashions, but with apparent concern for expression and communication. (Among the composers of the past whom he mentions as influential in his own work are Sibelius, who is generally undervalued today, as well as Brahms, Mahler and Stravinsky, who are certainly “in,” and, in Albert’s earlier years, Bartók and Ives.)

To Wake the Dead, composed 1977-1978, marked the beginning of Albert’s response to that [James Joyce] literary stimulus. The song cycle TreeStone was the second, RiverRun the third, and Flower of the Mountain, composed for Lucy Shelton in 1985, brought the total of his Joycean works to four. Since the motivation for the first three of these came from Finnegans Wake, and Flower of the Mountain is a setting of the final pages of Molly Bloom’s long soliloquy in Ulysses, it is surprising to have Albert tell us that A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was the only work of Joyce’s he had read in its entirety when he composed most of these works. “I didn’t really read Finnegans Wake from beginning to end,” he says; “I used it more or less as a reference work, the way other composers might use the Bible, finding certain passages in it that lend to musical treatment of a direct sort, such as actual song settings, or a more indirect sort, such as my symphony. The symphony in not really a programmatic work in the accepted sense: it represents my response to a Joycean stimulus, but that response is not the type that involves an attempt at direct imagery.”

Albert is attracted, he says, to “the very musical rhythm of Joyce’s language; among 20th-century poets, only T.S. Eliot and perhaps Yeats strike me as being more musical in that respect. The flashes of imagery are marvelous, and there is that convoluted nostalgia—for under all his artful disguises and arcane language one finds a basic Irish sentiment which I for one like so much. In his work I discovered what I regard as a foreign language—a language enormously suggestive of English, and of course directly related to English, but essentially a foreign language. Through this invented language he has been able to elusively chronicle man’s endurance of tragedy and the whole human comedy . . . Finnegans Wake does not produce literal or direct images for me, but works in terms of generalized suggestions and impressions. This stimulus produces a sort of mental atmosphere that provides for me an escape from contemporary America—in much the same way, I suppose, that the theological stimuli to which Bach responded provided him an escape from the realities of early 18th-century Leipzig.”

Immediately after the premiere of RiverRun Rostropovich expressed his great enthusiasm for the work and his determination to record it. He performed the symphony again with his Washington orchestra two seasons later, and in those concerts of May/June 1987 RiverRun became the first American work to be recorded by him as conductor. The score, dedicated to Rostropovich, the National Symphony and the Hechinger Foundation, calls for three flutes, piccolo and alto flute, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, two bassoons, contra-bassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, vibraphone, xylophone, cymbal, triangle, glockenspiel, gong, chimes, bass drum, two harps, piano and strings. The composer provided this note of his own for the premiere:

Composer’s Note

By Stephen Albert

The Symphony RiverRun is one of two works begun at roughly the same time [early 1983]. The other work, TreeStone, is a song cycle based on selected passages from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, the text of which forms a wildly distorted version of the Tristan and Isolde story, and is scored for soprano, tenor, and twelve instrumentalists. Both works were completed together, and they share the same musical materials. (I actually worked on the two compositions in constant alternation, though the materials common to both were put into TreeStone first.) They differ in the number and ordering of their movements, as well as their formal architecture and instrumentation.

The symphony and its four movements carry descriptive titles, not because the work is specifically programmatic, but in order to suggest its broad kinship to the song cycle (in which Ireland’s Liffey River plays such a dominant role), and also to acknowledge the importance that Joyce’s atmosphere in the TreeStone text had on my frame of mind. I did not do my composing to a specific programmatic outline; the titles of the symphony’s four movements were affixed only after each of the respective movements was completed. The title I gave to the work as a whole, RiverRun, is in fact the very first word of the first sentence of Finnegans Wake.

The opening movement, Rain Music, is meant to convey the origins of a river. After the sharply accented chords of the movement’s introduction, the music becomes quieter, suggesting an atmosphere of expectancy. The momentum of the movement gathers speed and power, finally ending with a return to the movement’s opening chords, now climactically pitted against a repetition by the brass, bells, piano and harps of melodic fragments heard earlier in the movement.

While the full orchestra is heard throughout the two other movements, the inner ones are more lightly scored. The second movement, Leafy Speafing, omits the big brass and percussion; it is essentially for the strings, with two horns, woodwinds, piano, vibraphone, and harps. The alto flute’s languid, cadenza-like opening is followed by a more tightly focused thematic idea from the solo viola. The two instruments then engage in a quiet dialogue against the softly changing chords until the river’s relentless current reappears, now in a new guise. In mid-movement the opening dialogue reappears and is extended, but is soon swept away once again by the current. At the end is a coda in which the Voice of the River, held back until now, is heard for the first time from the horns in sharp relief over a rolling arpeggiated figure in the harps, woodwinds and strings. This brief concluding episode contains a sort of preview of what is to be encountered later as the central material of the final movement.

Instead of the conventional scherzo and trio, the third movement, Beside the Rivering Waters, is a fragmented march and scherzo. It opens with a children’s song. The march, for the pit band, follows, and we are engulfed in a boozy wake, a lively funeral in which the participants try to escape their own fears of death and disconnection. The music of these two contrasting sections has a sort of music-box quality, but is altogether more raucous than that term might suggest—pronouncedly so when the little pit band is interrupted, as it is regularly, by the large massed brass. The scherzo, in the middle, brings a return of the current, represented by a repeated idea, performed in turn by harp, piano and muted strings over a whirring background provided by those instruments in various combinations. Then the march returns abruptly, followed by the children’s tune—which is in turn transformed into a raucous pub song for the piano, saxophone and trumpet. The march, the children’s tune and the subdued strains of the funeral are finally heard moving off in the distance.

Throughout the forth movement, RiversEnd, musical ideas from the preceding movements are recalled, while new elements (really old ones reconstructed and transformed) begin to appear as well. Night is falling, and the river is moving quietly into darkness. As it approaches the open sea its momentum builds and it soon becomes a torrent spilling into the ocean. The movement ends quietly, bringing the entire symphony to a close in an atmosphere of suspension and stillness.

Liner Notes from the 2007 Naxos CD

Liner notes written by Ron Petrides:

In 1983, the Sydney L. Hechinger Foundation commissioned Stephen Albert to write a work for the National Symphony Orchestra. That commission came about quite by chance: The 20th Century Consort, a group made up of members from the National Symphony Orchestra, had performed Albert’s song-cycle To Wake the Dead, a recording of which was heard by Mstislav Rostropovich, the orchestra’s conductor. Albert received a phone call stating, “Slava wants to see you about writing a piece for the band,” to which he replied, “Who’s Slava? What band?” Rostropovich suggested that the work be a mass, but Albert suggested a symphony instead; the result was the symphony RiverRun.

The symphony is Albert’s reflection on the cycle of Life, for which the River serves as a metaphor. The scope of ideas—life/death/rebirth—recall themes present in works of Gustav Mahler, whom Albert greatly revered.

RiverRun is a companion piece to Albert’s song cycle TreeStone, with texts excerpted from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. The composer was at work on TreeStone when he received the commission for RiverRun and accordingly worked on both simultaneously. A comparison of the two compositions opens a window into the deeper psychological meaning of the music. According to Albert, “Both works were completed together, and they share the same musical materials. (I actually worked on the two compositions in constant alternation, though the materials common to both were put into TreeStone first.) They differ in the number and ordering of their movements, as well as their formal architecture and instrumentation.”

The composer, however, was quick to dispel any notion of Symphony RiverRun as a programmatic work. The subject material provided a stimulus for composition—the music’s descriptive qualities are a reaction to that stimulus.

In this, his first symphony, Albert adheres to the convention of the four-movement symphonic design. However, the form of each movement is idiosyncratic.

The opening movement, Rain Music, is an allegro with an introduction. However, the composer dispenses with sonata-allegro form. In the introduction if you listen closely, you can almost hear a fragment of the opening measures of Beethoven’s Pathétique sonata. By the third measure, the ascending thirds are transformed, and we enter Albert’s personal world. In the wake of two stark sounding chords in the strings and winds, the introduction continues with tremolos in the strings, light winds, harp, and piano, suggesting drops of rain falling upon the Liffey River. Against this backdrop, short melodic fragments are woven into the orchestral fabric. These become thematic and appear later in the Symphony.

Throughout the Allegro, ostinatos (repetitive patterns) performed in the low register depict the incessant current of the river and are occasionally interrupted by chordal passages. The final climax occurs at the end of the movement as a series of four chords, similar to the pair of stark chords heard in the introduction, now in reverse order. The prolonged closing chord sounds unresolved.

The second, slow movement of the symphony, Leafy Speafing, contrasts with the first not only in tempo but also in its orchestral palette. Brass and percussion, which were featured prominently in the first movement, are absent. The ensemble emulates a chamber orchestra. The movement is laid out in four sections. Exchanges between featured soloists, duos or trios against the orchestra characterize the first and third, while alternation between ostinato and contrapuntal passages distinguishes the second and fourth. Ostinato passages increase in intensity until reaching a climax, signaling the section’s end. During the coda a new theme is introduced, labeled by the composer as The Voice of the River, which will figure prominently in the fourth movement.

The form of the third movement is evocative of a classical scherzo (or minuet) and trio, but Albert instead uses a scherzo preceded by a march. A jagged fanfare in the opening measures is followed by a tune, marked in the score, “like a children’s music box,” and is heard against an accompaniment that sounds harmonically askew. This tune is the only tune notated in Finnegans Wake, with Joyce’s lyrics. Albert set the tune with Joyce’s lyrics in another of his song cycles, To Wake the Dead. Originally it is an Irish folk song titled “Mush Mush.” This tune is succeeded by a March Theme, which purposely does not line up with its accompaniment, suggesting a nightmarish boozy wake.

The scherzo contrasts with the “march and wake” as the current of the river returns in the form of whirring ostinatos in the strings. Against this backdrop, a new theme is introduced in the solo violins and cello, developed from materials introduced earlier. After the return of the March Theme and the “children’s music-box” theme, now cast as a rowdy pub song, the music gradually fades into eerie silence followed by a haunting final chord—whose pitch material is derived from the now familiar arpeggiated motif spread across extreme registers.

In the fourth movement Albert dispenses with traditional forms, and instead develops his own, characterized by three climactic sections, each surpassing the previous in intensity, separated by more suspenseful sections. The movement opens with a theme introduced by the horn that is answered by the arpeggiated motif in the lower strings, evocative of the river’s churning waters. Against this background, a theme labeled by Albert as The Voice of the River, arises in the horn and violins. Various instrumental combinations utter the theme, until its transformation is given to a lone oboe, which ushers in a suspenseful section, set against a tri-tone pedal point tremoloed in the double basses. The first and third climactic sections begin with an ascending theme in the lower strings, joined by brass and winds consisting of overlapping half-diminished chords. The climax suddenly breaks off, followed by materials evoking imagery of the “children’s music-box” heard in the third movement. An ascending sequence of minor thirds in whole tones initiates the second climactic section. A beautiful theme performed by the solo oboe is heard in the following section. The third climax is the longest and most agitated, featuring tremolos in the piano. Here, the Voice of the River theme is joined with the theme heard in the solo oboe. These themes are repeated with growing intensity. However, the final statement in the brass and winds marked ff, is incomplete, interrupted by a motif taken from the first movement in the glockenspiel and piano. This signals the beginning of the coda where the Voice of the River theme is juxtaposed with earlier motifs, until they gradually fade away. The final note of the river theme is C#, the same as the final bass notes in the first three movements. However, C# is heard together with D# sustained in the double basses, which, in conjunction with the orchestral diminuendo seems less final, and perhaps suggests the unending cycle of life with all of its uncertainties.

Recordings

There are two commercial recordings of Symphony RiverRun. Both are excellent, but the more recent Polivnick recording from Naxos benefits from a sharper instrumental definition, and has an overall brighter sound field.

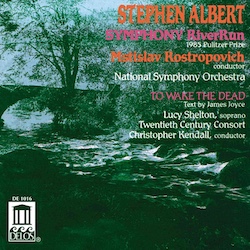

Albert: Symphony RiverRun (1998)

Conductor: Mstislav Rostropovich

Musicians: National Symphony Orchestra

CD: Symphony RiverRun; To Wake the Dead. Delos D/CD 1016 (1998)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

The première recording of Albert’s Pulitzer Prize-winning symphony, recorded in 1987 at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. It was paired by Christopher Kendall’s 1982 recording of To Wake the Dead, originally issued on LP by the Smithsonian Collection.

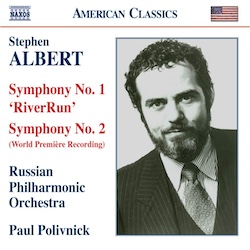

Albert: Symphony No. 1 “RiverRun” (2007)

Conductor: Paul Polivnick

Musicians: Russian Philharmonic Orchestra

CD: Symphony No. 1 “RiverRun”; Symphony No. 2. Naxos 8.559257 (2007)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: Naxos | YouTube

On this Naxos “American Classics” disc, Symphony RiverRun has been retitled Symphony No. 1. It’s paired with the world première recording of Albert’s outstanding Symphony No. 2. Both were recorded at Studio 5 of the Russian State TV & Radio Company Kultura in Moscow in April 2005.

Additional Information

Symphony RiverRun Wikipedia Page

A short page on Albert’s symphony

Stephen Albert “Overtones” Interview

Overtones, 1988. A very engaging and informative interview with Stephen Albert, who discusses his relationship to James Joyce, his compositional process, and his thoughts on modern music.

Stephen Albert Interview with Bruce Duffie

WNIB, 9 December 1990. The transcript of a telephone interview conducted with Stephen Albert.

Runyan Program Notes

William Runyan’s program notes for Symphony RiverRun.

Stephen Albert: Other Joyce-Related Works

Stephen Albert Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Stephen Albert profile.

To Wake the Dead (1978)

This remarkable song cycle is subtitled, “Six Sentimental Songs and an Interlude after Finnegans Wake.”

TreeStone (1983)

Albert’s second song cycle inspired by Finnegans Wake, TreeStone is loosely based on the legend of Tristan and Iseult.

Flower of the Mountain/Sun’s Heat/Distant Hills (1985-1989)

Flower of the Mountain is based on Molly’s soliloquy in Ulysses. In 1989 Albert paired it with another Ulysses-inspired song, Sun’s Heat. Together they form a two-movement piece called Distant Hills.

Ecce Puer (1992)

A setting of Joyce’s final poem for soprano.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 16 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com