Joyce Music – Boulez: Répons

- At May 18, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

Répons

(1981-84; 43-45 min)

For orchestra, six soloists and electronics.

1. Introduction

2. Section 1

3. Section 2

4. Section 3

5. Section 4

6. Section 5

7. Section 6

8. Section 7

9. Section 8

10. Coda

I can find in his writings the fundamental preoccupations of contemporary music. To have seen him and heard him speaking his own texts, accompanying them with cries, noises, rhythms, showed us… in short, how to organize delirium. What non-sense, it will be said, what an absurd mixture of terms. What? Would you believe only in the vertigo of improvisation, in the power of an “elementary” ritualization? More and more, I imagine, to make it effective, we will have to take delirium and yes, organize it.

—Pierre Boulez on Antonin Artaud

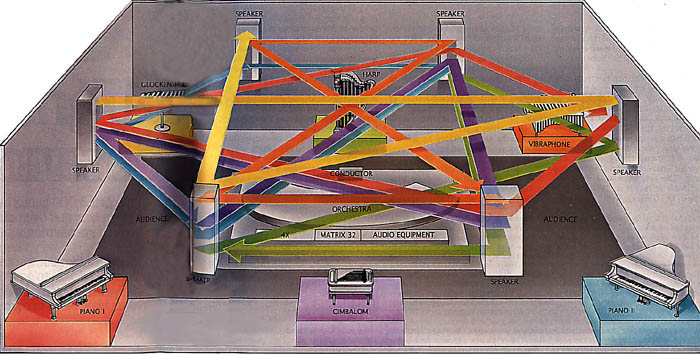

Produced at IRCAM in the early 1980s, Répons marked Boulez’s return to large-scale, original composition after a lengthy period of conducting. Around 45 minutes in length, Répons is scored for an orchestra, a digital processor, six loudspeakers, and six “solo” instruments: two pianos, a harp, a glockenspiel/xylophone, a vibraphone, and a cimbalom, an old Hungarian instrument similar to a large dulcimer. The six soloists are arranged around the perimeter of the audience, who sit in between the soloists and the central orchestra. The soloists are separated from each other by the six loudspeakers, which face the audience.

Répons unfolds as a spiraling set of dialogues between the orchestra, the soloists, and the electronics. (Boulez has declared the title to be a portmanteau word combining the idea of “dialogue” and “response.”) Among his inspirations for Répons, Boulez has cited the “cyclical” works of James Joyce and Franz Kafka, whose “logic consists in leading you towards something new that you none the less think you recognize,” a technique that “involves illusion and ambiguity.”

Though it forsakes traditional melody and structural development, Répons is quite unlike Boulez’s earlier serial pieces, which aggressively follow their 12-tone mathematics in the pursuit of a new language. The pitch sequences and harmonies remain atonal, but Boulez has drawn from other modern compositional elements, including electronic processing, the manipulation of spatial acoustics, and even a quasi-Minimalist use of repetitive cells. While Boulez has employed these elements in the past, Répons feels more balanced, natural, and dramatic—like a tropical storm summoned from a confluence of stylistic fronts. Indeed, Répons recalls Debussy’s expressionistic portrait of the sea, La Mer—the music rolls, undulates, murmurs, surges and swirls, alive with its own potential for infinite creation.

Organized Delirium

Répons opens with “Introduction,” a six-minute wind-up of the central orchestra. Events occur quickly, miniature figures passed from instrument to instrument like spinning plates. There’s a playful precariousness to the music, as if one instrument should slip, the entire structure would come tumbling down. The muted horns emphasize this feeling of fragility, an anxious wobbling above the strings. As the anticipation builds, the vortex expands to include the six soloists waiting at the perimeter. (Many performances of Répons use complex lighting effects as well, usually keeping the soloists in the dark until their introduction.) Section 1 begins with these instruments waking up, each announcing its presence with a flourish of arpeggiated notes. These runs are immediately absorbed by the computer, transformed, and re-released; colorful ripples of sound flowing back into the unfolding work. Unlike many contemporary electroacoustic pieces, the processing in Répons feels warm and surprisingly organic, an extension of each instrument’s natural timbre rather than a futuristic barrage of bleeps and squonks. Plucked and hammered strings dissolve in a liquid shimmer, while vibraphone and glockenspiel fade into distant, mechanical rhythms. There’s the sensation that metal and wood are slowly sinking from memory—the dreams of an old locomotive, submerged and forgotten underwater.

Section 2 continues to develop the soloists, spinning them off into brief exchanges with the orchestra or knotting them together in dense clusters of sound. The strings surge back to life in Section 3, their increasing friction heating the orchestra to a rollicking boil. The soloists occasionally interject with thorny comments or angry retorts, but there’s no resolution to the bickering. A dark mood falls across Répons as we transition to Section 4. The most unsettling sequence in the work, the strings sustain an unresolved atmosphere of tension while the soloists bubble aimlessly beneath a glassy, undulating drone. As the horns grow more aggressive, the music acquires an ominous urgency, heaving swells of sound that never quite peak. The orchestra falls back in mock exhaustion, and Section 5 proceeds across a fractured soundscape of agitated strings and batteries of skittery percussion.

Eventually the atomized music begins to coalesce, and a halting fanfare on the woodwinds heralds the arrival of Section 6. The emotional climax of Répons, this sequence is a musical gyre of increasing frenzy: sawing strings, whirling piccolos, repetitive figures hammered out on piano, harp, and percussion. Boulez once referred to music as “organized delirium.” Nowhere else in his oeuvre does this description better apply—one can almost hear Willy Wonka crying, “Faster! Faster!” as the work plunges headlong into madness. The frenetic pace continues into Section 7, but here we find more “organization” than “delirium.” Individual instruments separate from the maelstrom like voices from the whirlwind, and once again distinct figures and patterns emerge.

The final numbered sequence, Section 8 begins with an almost-hummable melody played on piano, the pedal firmly depressed. The orchestra gathers itself into a surreal, slithery march, complete with tick-tock pizzicato and horns that approach jazziness—approach being a key word here; think Frank Zappa’s “Jazz from Hell.” Soon the orchestra is spinning plates again, and a series of disjointed piano runs brings us to “Coda.” Répons does not conclude as much as it retreats in the distance, a winding-down of pedaled glissandos, desultory fanfares, and submarine bells. Like a storm passing over the horizon, its thunders, flashes, and gales have become strangely tranquil, reduced to an eerie calm when viewed from afar.

Répons performed at the Park Armory, NYC 2017

Répons performed at the Park Armory, NYC 2017

Excerpts from an Interview between Jean-Pierre Derrien & Pierre Boulez

Jean-Pierre Derrien: Just as you were broaching Répons, you were also preparing orchestral versions of Notations for piano (1945), which are all very short pieces. How do you see the contrast between them?

Pierre Boulez: Notations is made up of pieces virtually all based on a single idea…. Répons, by contrast, is based on different types of material. Its title refers not just to the dialogue between soloists and ensemble or to the dialogue between the soloists themselves or to the dialogue between what is transformed and what isn’t, but also to the dialogue between different types of material: the term “response” is a portmanteau word.

The piece is cast in the form of a spiral, which I created in several stages. An example that comes to mind from the world of architecture is the Guggenheim Museum in New York, which was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and which has a gently sloping, spiral-shaped interior. As visitors wander through the exhibition, they can invariably see what they are to see at close quarters the very next moment, as well as what they have just seen and which is already some distance away. I was much struck by the way in which past and present interact and exactly the same conditions are magnified or transformed as the visitor passes to a lower or higher level. To use a musical term, Répons is a set of variations in which the material is arranged in such a way that it revolves around itself.

Derrien: Is there in this conception a pointer to techniques more usually associated with the novel?

Boulez: Yes, of course, although this feature is also found in the asymmetrical structures of Mahler’s symphonies. To return to literature, it raises the whole question of narrative structures such as are found in Proust, Joyce, Musil and Faulkner, among others. There was a time when I was particularly attracted to the novelistic technique of Kafka and Joyce: their logic consists in leading you towards something new that you none the less think you recognize. This technique involves illusion and ambiguity and is of capital importance for me.

Jean-Pierre Derrien: The spiral is probably the clearest metaphor of your approach to composition: you have been writing practically the same work since you started composing, only the particular form is different for each occasion. Can one say that your approach aims at ensuring that the material remains homogeneous?

Boulez: Yes, and in that sense I am not at all like musicians such as Berio or Berg or, of course, Mahler, all of whom accept heterogeneous elements and integrate them into their works. For my own part, I find it impossible to integrate extraneous elements in this way, unless I have already translated them into my own individual language. That is why I do not keep writing the same work, even though my approach is always guided by the same criteria. There is no doubt that my world is now more elaborate than it was before. It is basically the same with Proust, where the beginning and end of A la recherche du temps perdu are clearly by the same writer, but the whole nature and outline of the developments are different.

Liner Notes from the DG 20/21 CD

Liner notes written by Andrew Gerzso:

Répons was commissioned by Southwest German radio for the Donaueschingen Music Festival and was first performed on 18 October 1981, by the Ensemble InterContemporain (conducted by the composer) using technology developed at IRCAM, the musical research institute which is part of the Pompidou Centre in Paris. The work is dedicated to Alfred Schlee, a longtime friend of the composer and former director of Universal Edition in Vienna. Incidentally, the work contains a hidden reference to another close friend, the conductor and patron Paul Sacher. The letters in the last name of one of this century’s great musical benefactors are used as the departure point for creating the harmonic material which structures the entire composition.

The title of this work refers to the responsorial form of Gregorian Chant in which a solo singer alternates with a choir. Two things are of interest in this form: first of all, the relationship between “the one and the many” and, secondly, the spatial element introduced by the distance separating the soloist and the choir. In this simple medieval form one finds some of the musical ideas which occur throughout Boulez’s work: the taking of a simple musical idea and making it proliferate, the alteration between solo and collective playing, and the movement of sound in space.

Recordings

Boulez: Répons (1998)

Conductor: Pierre Boulez

Musicians: Ensemble InterContemporain

CD: Répons & Dialogue de l’ombre double. Deutsche Grammophon 457 605-2 (1998)

Purchase: [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

Online: YouTube

Répons has only one commercially available recording, released as part of Deutsche Grammophon’s excellent 20/21 imprint. The recording is spectacular, with IRCAM engineers doing their best to balance and spatialize its complicated sound world to stereo acoustics. (Ah, if only a 5.1 surround sound version would come out…) Répons is coupled with Dialogue de l’ombre double, a piece for clarinet and six loudspeakers. Similar in some ways to Répons, this work features a soloist playing against a pre-recorded “double.” Highly recommended. (This CD also won the 2000 Grammy Award for best contemporary classical album.)

Online Video

The following excerpts and live performances are available on YouTube. They are listed in order of general quality, with the best recordings placed first.

Boulez: Répons

Ensemble InterContemporain, Conducted by Mattias Pintscher. Posted 2015.

A masterful performance by the always-amazing Ensemble InterContemporain.

Boulez: Répons

Ensemble InterComporain, Conducted by Pierre Boulez. Posted 2015.

This live performance was recorded at the 1992 Salzburg Festival Concert. The great Pierre-Laurent Aimard plays one of the pianos.

Boulez: Répons—Un Film de Robert Cahen

Ensemble InterContemporain, Conducted by Pierre Boulez. Posted 2012.

This excerpt is from a 1986 film of Répons, directed by Robert Cahen. Unfortunately, the clip only shows the first 10 minutes of the 46-minute long original film.

Boulez: Répons

This video follows the DG recording with a scrolling score.

Additional Information

Répons at Scenography Today

This wonderful page has some excellent photographs of a rare performance of Répons in New York City, October 6–7, 2017.

Répons Wikipedia Page

You can read more about Répons and its original reception at Wikipedia.

Pierre Boulez: Other Joyce-Related Works

Pierre Boulez Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Pierre Boulez profile.

Third Piano Sonata (1958)

A complex labyrinth of sound and theory, this infamous piece of Modernist music was partially inspired by Joyce.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

First Posted: 10 January 2004

Last Modified: 17 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com