Interview with Steven Ricks

- At February 15, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Pynchon, The Modern Word

0

0

Computer Love:

A Conversation with Steven Ricks

Steven Ricks

Steven Ricks is an American composer who embraces traditional instrumentation, electronics, and electroacoustic music. He’s also an avid fan of popular music, which he explores as co-host of the freewheeling podcast Let the Music Be Your Master. Ricks currently teaches music theory and composition at Brigham Young University in Utah. His latest release is Assemblage Chamber, available from New Focus Recordings. In 2005, Ricks composed two pieces based on Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow—American Dreamscape and Beyond the Zero. Collected on the 2008 Bridge CD Mild Violence, both pieces were featured and reviewed on Spermatikos Logos’ “Pynchon On Record” page. In February 2022, Allen B. Ruch of the Modern Word talked with Steven Ricks about the influence of literature on his music, his development as an electroacoustic composer, and the music he finds most inspirational.

Interview

Allen B. Ruch: Hello, Steve! Thank you for taking the time to talk.

Steve Ricks: Very happy to talk about my favorite subjects—myself and my music! ☺ Let me just say it was a very pleasant surprise to hear from you over the Holidays and I’ve really enjoyed our exchanges so far.

ABR: Thank you, I feel the same. As you can tell from the Spermatikos Logos review, I’m a big fan of Mild Violence, particularly the way you incorporate electronics into your work. Sometimes electroacoustic music can feel a bit gimmicky, but with these pieces, it seems essential. What are some of your first experiences with electronic music?

SR: I love this quote by Brian Eno, written in 1999 as the opening to his essay in the OHM: the early gurus of electronic music anthology: “If you’re under ninety, chances are that you’ve spent most of your life listening to electronic music.” My earliest experiences with music technology, I suppose, were using various cassette recorders and boom boxes to dub music off the radio and then later my friends’ LPs.

ABR: Hello, Generation X! Did this lead to any experimentation with the medium?

SR: I remember once recognizing that a little broken tape recorder I had would record onto one channel of a cassette while leaving the other intact, essentially functioning like a very low-budget two-track recorder. I ended up recording the first vinyl single I ever purchased, Kraftwerk’s “Computer Love,” on each channel of the cassette, the right channel a couple beats behind the left channel. My first experience with phasing, I suppose, à la Steve Reich, before I ever heard of him.

But really, my earliest interests in anything directly electronic were through bands like Kraftwerk, Depeche Mode, etc.—‘80s New Wave, synth pop, etc., sometimes veering in more experimental directions with performers like Laurie Anderson or Devo. My own musical experience in my pre-college days was focused on playing trombone in public school bands and orchestras, and then near the end of high school in an after-school jazz ensemble led by Grant Wolf at Mesa Community College. Great musical experiences, but mainly in what would normally be considered the acoustic realm.

ABR: Always happy to hear a shout-out to Devo! I myself am the proud owner of an energy dome.

SR: I love Devo—The Men Who Make the Music was mind-blowing to the young teen me and my friends, and the strangeness of the pseudo-science-mythology or whatever that permeated their songs and gear is so great. Unlike you, I never did acquire an energy dome, dangit. That and not ever seeing them live are two big regrets.

ABR: Yeah, that “mythology” is key—Devo really created their own syncretic cult. Among other more outré sources, Devo were also influenced by modern literature, including William S. Burroughs, Kurt Vonnegut, and Thomas Pynchon. In fact, Jerry Casale claims that “Whip It” was partially inspired by Gravity’s Rainbow. How were you first exposed to Pynchon?

SR: I’m a Laurie Anderson fan, and her album Mister Heartbreak was on regular rotation in my listening for the first few years after it came out, and beyond, obviously including the song “Gravity’s Angel.” I listened to and loved the song for years, puzzling over the “for Thomas Pynchon” dedication but not really knowing or figuring out who that was.

ABR: That was my own introduction as well! “Who is this guy, and why are his friends thinking about ham and cheese sandwiches?”

SR: Fast forward to spring break 1996, I’m on the East coast visiting friends and taking the train from DC to NYC, or NYC to Boston. I end up sitting by a young guy who’s studying literature at Princeton, including a class from Toni Morrison (WOAH) and in the course of conversation he says Thomas Pynchon is one of his favorite writers. OH…so he’s a writer. I probably say something like “I love this song by Laurie Anderson called ‘Gravity’s Angel’ dedicated to him,” really intelligent, and then he probably said “well it’s inspired by his novel Gravity’s Rainbow.” Duh.

So when I find myself in a used bookstore in New York, I pick up a copy of Gravity’s Rainbow, a dog-eared 1973 Penguin edition with the orange cover. I have a few tries at it that year, then buy the Steven Weisenburger Companion a year later in Salt Lake City and finally dig in. Really the first novel that complex I’ve tackled, before or since. (I still have Infinite Jest on my shelf, having read the first 40 pages a couple times… YOU’RE NEXT IJ!)

ABR: I fully endorse that decision! Infinite Jest is a tremendous book, wonderfully complex, but very humane as well. So what about Gravity’s Rainbow made it meaningful enough to inspire two pieces?

SR: It made quite an impression for many reasons… I was really blown away by how the “rocket” as a symbol/metaphor/motif/whatever permeates the novel on so many levels, and then how the notion of the sonic characteristic of the V2 is connected to Pavlovian responses, is connected to Slothrop, etc. As you’ve already mentioned, I have two works specifically inspired by the novel—American Dreamscape which is inspired by the famous Charlie Parker “Cherokee” passage, and Beyond the Zero, which is inspired more generally by various concepts and ideas from the work. I finished both pieces in 2005, so I was writing them at the same time. I was immersed in thinking about ideas from the novel, and I think the complexity of the ideas and the interest in expressing the spiritual, supernatural, and surreal elements of the text fit well with my interest in using electronics with live instruments.

ABR: Let’s talk about American Dreamscape first. As you say, the piece was inspired by the famous “Cherokee” passage, where Slothrop descends into the toilet of the Roseland Ballroom to retrieve his mouth harp. Slothrop’s Orphic journey brings him to a surreal underworld, one where Pynchon explores the dark underbelly of American history, particularly regarding race and genocide. Although the sequence itself is many pages long, this section is the most often quoted:

“Cherokee” comes wailing up from the dance floor below, over the hi-hat, the string bass, the thousand sets of feet where moving rose lights suggest not pale Harvard boys and their dates, but a lotta dolled-up redskins. The song playing is one more lie about white crimes. But more musicians have floundered in the channel to “Cherokee” than have got through from end to end. All those long, long notes…what’re they up to, all that time to do something inside of? is it an Indian spirit plot? Down in New York, drive fast maybe get there for the last set—on 7th Ave., between 139th and 140th, tonight, “Yardbird” Parker is finding out how he can use the notes at the higher ends of these very chords to break up the melody into have mercy what is it a fucking machine gun or something man he must be out of his mind 32nd notes demisemiquavers say it very (demisemiquaver) fast in a Munchkin voice if you can dig that coming out of Dan Wall’s Chili House and down the street—shit, out in all kinds of streets (his trip, by ’39, well begun: down inside his most affirmative solos honks already the idle, amused dum-de-dumming of old Mister fucking Death he self) out over the airwaves, into the society gigs, someday as far as what seeps out hidden speakers in the city elevators and in all the markets, his bird’s singing, to gainsay the Man’s lullabies, to subvert the groggy wash of the endlessly, gutlessly overdubbed strings. . . . So that prophecy, even up here on rainy Massachusetts Avenue, is beginning these days to work itself out in “Cherokee,” the saxes downstairs getting now into some, oh really weird shit. . . .

What about this passage particularly attracted your interest as a composer?

SR: When I first read that paragraph I just loved it—loved the way it was like a jazz solo, riffing on race and music and weaving all this complex stuff and relationships into this flow of words. I love things with layers, and things loaded with meaning, references, and associations, so Pynchon pointing out all the loaded racial elements of white Slothrop in this setting and Charlie Parker, Black icon of jazz playing a tune called “Cherokee,” etc., it just got my head spinning and wondering how I could create music/sound that might do something similar. So I was obsessed with that paragraph for a while, had it printed and on my wall or just around to read and think about, until I finally solidified ideas for writing a piece inspired by it.

ABR: Did the song itself influence your writing for the alto saxophone in American Dreamscape? There’s certainly nothing as simple as direct quotation…

SR: “Cherokee” is influential in at least three specific ways I can mention, and maybe other less obvious influences are there as well. The opening of the piece is meant to evoke the scene of being in a jazz club. I recorded my friend and colleague Steve Lindeman, a jazz pianist and composer, soloing over “Cherokee” changes, and then added restaurant/club sounds in the background. The pitch/tuning of his playing starts to shift, gradually, until when he hits the bridge things start swirling around the room—when it’s performed live quite literally with the use of speakers surrounding the audience. Perhaps some connection to venturing down a toilet bowl there?

Then when we emerge on the other side of this crazy, swirling bridge (the musical “bridge” of “Cherokee”), we’re in a kind of strange, Milton-Babbitt-esque bebop world with transformed changes, electronic piano sounds that range from the acoustic piano to the DX7 and beyond, and then these strange alto sax interludes which are meant to sound “old” in terms of audio quality, but “new” or “modern” in terms of their pitch/rhythm. The percussive tapping we hear behind the sax lines is actually Charlie Parker’s foot tapping in a recording of “Koko,” his new tune to go with “Cherokee” changes.

Finally, the dreamlike section that emerges after the “live” sax joins this upbeat opening, about 4:18 in the Bridge Records recording, uses the “Cherokee” tune from the A section of the song as the basis for all the fat bass notes, though the pentatonic tune is here mapped onto the whole-tone scale.

ABR: “A Milton-Babbitt-esque bebop world” is not a bad subtitle for the piece! It’s fascinating to get a glimpse “under the hood,” so to speak: there’s a lot going on there. So…if I can return to the toilet bowl. While American Dreamscape is hardly a programmed soundtrack to Slothrop’s journey, Jeremy Grimshaw’s liner notes for Mild Violence claim—perhaps alluding to Pynchon’s description of Spike Jones’ music—sometimes “a gunshot is a gunshot.” What are the “gunshots” in this piece? Are there any sections you clearly identify with sequences from the text?

SR: As I mentioned, I think emerging from the electronic opening to where the acoustic instruments first enter is analogous to Slothrop emerging after going through the toilet bowl. I think from there on I really embrace the “dreamscape” aspect of what I’m going for, and inspirations from the book and other sources are sort of free flowing and included as they arise.

ABR: Are there other musical influences on Dreamscape beyond Parker?

SR: The sound of Jimi Hendrix’s performance of the National Anthem at Woodstock was very much in my mind for the sax solo from 6:00–8:00 in the recording, up to where the video comes in.

ABR: About that video. Towards the end of American Dreamscape, there’s a dramatic electronic effect that sweeps through the music, a kind of cindery crackling. The score reads only “Electronic sax solo with video, ca. 3 minutes.” What was the original video, and how did it factor into live performance?

SR: My friend, filmmaker Ethan Vincent (who was director for the video portion of my monodrama Medusa in Fragments), made a short, abstract film to go along with this electronic interlude—the sound/music was created first. The video is posted on my YouTube channel and during a live performance of Dreamscape is meant to be projected on a large screen behind the performers, or even onto the performers.

I think of it as a sort of vision, or fever dream, or whatever you’d like to call it… a sort of culminating spiritual moment in the piece. The crackling/sweeping is created by layering and looping some close-mic’d saxophone key clicking provided by a then BYU student Richard Nobbe (who also provided all the prerecorded/manipulated playing in the opening and this vision section). The first two descending melodic notes, which create a tritone, connect with other American songs that were in my mind for some reason—including the first two notes in the verses of Michael Jackson’s “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” and Pearl Jam’s “Even Flow.”

ABR: I would have never connected those two songs before—I’ll remember that for my next “avant-garde composer trivia night!” One last question about the piece. In Gravity’s Rainbow, the toilet sequence is fairly R-rated, involving fears of rape, let alone some pretty impressive scatological passages. How did you choose to confront these elements in your music? Did you run into any raised eyebrows along the way?

SR: I think that while my music is extreme in some ways, it’s abstract and difficult to interpret specifically because it’s purely instrumental/electronic music without text. I think the only raised eyebrows I’ve experienced have come from a dislike of dissonant harmonies or extreme juxtapositions or something, but not really from feeling the music is somehow representative of anything “R-rated.” I mean reading Gravity’s Rainbow was certainly an education for me, no question… the Captain Blicero stuff… but I think what I was mostly interested in in Dreamscape were the musical and racial allusions and references, and how I could deal with them in a purely instrumental work.

ABR: Maybe your first opera can be Captain Blicero’s House of Fun? Let’s move on to Beyond the Zero. You’ve already discussed your fascination with the novel’s V2 rocket. Aside from the literal “A screaming comes across the sky,” what else about Gravity’s Rainbow inspired this composition?

SR: First off, I just loved the phrase “Beyond the Zero,” the title of the first section of the novel, and I think a sort of poetic explanation of Slothrop’s strange ability to predict where the V2 rockets are going to hit. For me the idea of a zero point began to represent a specific point in time, or a specific event, like birth or death, but then the idea of things existing prior to or following these points. So I combined my belief in the immortality of the human soul with this idea of those two primary zero points—birth and death—and then imagined a musical work that would include a section representative of a pre-earth existence, then life on this planet, and finally an afterlife. In both instances of the zero point in my piece, the violin and electronic music/sound push beyond a clear threshold into new territory. It occurs to me now that the passage that inspired American Dreamscape is maybe related to this…that there is a kind of threshold crossed, following which we’re in a new and strange place.

ABR: I sense that threshold in both pieces. I think they share several similarities, particularly the endings—both feature a meandering fadeout along the highest register of the instruments. Was that deliberate?

SR: I don’t think the endings being similar was deliberate, though I can definitely notice tendencies I have and examples of doing the same thing over and over in pieces even when I think I’m doing something completely new.

ABR: Well, I think every creative person shares that tendency, so you’re in good company! Do you see any other linkages or connections between the two pieces?

SR: I think there are similarities in the way the acoustic instruments interact with the electronics, and also the notion that the electronics are used to represent and/or create spiritual or surreal elements in the pieces.

ABR: In his liner notes, Grimshaw says the electronics “swirl around the live performers like ghosts,” which is a terrific description. I love the sampled violin sounds in Beyond the Zero—it feels like the soloist has summoned a doppelgänger into a tense duet. How did you create the electronic parts of the piece?

SR: The electronics for both Pynchon-inspired works—and really any and all of my electronic music—are created in a pretty messy, multifaceted way. I love the unpredictability and strangeness of recorded-sounds-altered, in both simple and more complex ways, and have been obsessed with field recording via a hand-held recorder for many years now. I’m also interested at times in the purity of synthesized tones, virtual instruments, and physical modeling, so what my electronic pieces/parts usually end up being is a hybrid of recorded and synthesized sounds, all mixed together and manipulated in ways I think are interesting, and in ways I hope contribute to the success of the piece and fit with whatever acoustic instruments are involved.

As you noted in your review of Beyond the Zero, there are many recorded violin sounds I captured by close mic-ing a violin in a recording studio at BYU, including several high pizzicato notes, natural harmonics, hitting the instrument with the hand, etc. I then combined many of these sounds with synth/sampled violin and other sounds, mostly played by composed-out MIDI files, which are then converted to audio and potentially subjected to more manipulation or effects.

ABR: I feel the Pynchon pieces are also connected thematically to Waves/Particles. While this may just be the date of composition, I wonder if there’s also some other connection, conscious or not, between your interest in Gravity’s Rainbow and quantum physics. Any thoughts on this? (And by the way, I read the title of “Wrecked Angles” as “Wrecked Angels” until the moment this interview was prepared!)

SR: Well maybe I can CHANGE the title of that movement to bring it more in line with Pynchon! I can honestly say I wasn’t consciously making a connection between Waves/Particles and those other pieces, or to Gravity’s Rainbow either… it was inspired by a three-part Nova series on quantum physics hosted by physicist Brian Greene that I watched with my sons, and just reflecting on the idea of the dual wave/particle nature of matter. But maybe some stronger connections are yet to be found?

ABR: Along with spirituality and science, literature plays a significant role in your work. Besides Pynchon, you have several pieces inspired by poetry, haikus, short stories, and sacred texts. What was your first attempt to express your love for the written word using music?

SR: My OPUS ONE, probably the earliest piece I’m still happy to claim—maybe the best piece I’ve ever written?—is German Pancake, a setting of a, YOU GUESSED IT, German pancake recipe from the book Where’s Mom Now That I Need Her?, a Utah-published cookbook that was pretty popular as a gift to young folks starting to venture out on life’s great journey in the Southwest where I was from. It’s a punchy, humorous, short piece for soprano and chamber ensemble, with lots of overt text painting, an obvious nod to The Rite of Spring, and various techniques/harmonies/etc. that I’ve remained obsessed with through my whole composition career. I wrote the piece while studying with Michael Hicks at BYU—he became my colleague and is a good friend and one of the more influential people in my life.

ABR: A pancake recipe set to music—I can definitely see how that led to Gravity’s Rainbow! You’ve also been inspired by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., for instance on Ten Short Musical Thoughts, an homage to Kilgore Trout; and with your “Strange Enthusiasm” electronic pieces, which were inspired by Vonnegut’s short story, “Thanasphere.” In this story, the first astronaut discovers that the outer edge of earth’s atmosphere is populated by the voices of the dead. How did that guide your selection of samples and effects?

SR: I think as much as the voices of the dead, it’s the idea for me that anything/everything ever said/recorded/broadcast is floating around out there somewhere, and if we have the right equipment or if we hit the right frequency we can tune in and pick up a strange transmission. I think some of what happens is as an electronic music practitioner and someone who is constantly dabbling with the software on my computer to see what it can do, I continue to amass digital detritus, leftover fragments of sound that just sit on my hard drive or external drives or the cloud, waiting to be rediscovered and used. Often these little strange pieces are meant to use a discarded nugget, or rather I’m going through nuggets and find one I like and decide to turn it into something different, somehow.

ABR: Some of the “discarded nuggets” on “Strange Enthusiasm” are quite intriguing—the pieces evoke the mysterious vibe of Conet numbers, late-night public access TV, radio channels you can never locate a second time; to refer back to Pynchon, a kind of W.A.S.T.E. radio. Does the project stand as a finished EP, or is it still a work-in-progress?

SR: There was a time when I felt I could give myself over to creating strange short electronic works, like the kind in that “Strange Enthusiasm” collection, and be completely content… so I don’t think I can say I’ve formally abandoned the project, though I’m not really that active on Bandcamp so I’m not sure I see a current need to expand that collection. I think in some ways my Soundcloud page has become the place where I can continue to explore ideas suggested by Vonnegut’s “Thanasphere.”

Brian Christensen sculpture for Ricks’ “Force of the Mind,”

Brian Christensen sculpture for Ricks’ “Force of the Mind,”inspired by Vonnegut’s “Report on the Barnhouse Effect.”

ABR: Have you read Pynchon’s Vineland? I’m thinking specifically about the TV-obsessed, ghostly Thanatoids. I feel there are definite correspondences between Vonnegut and Pynchon here. And, are you still reading Pynchon? Have you followed up on any of his recent works?

SR: I’m embarrassed to say I haven’t read Vineland or followed up on any of his recent stuff—there’s a copy of Mason & Dixon sitting on my shelf, probably next to Infinite Jest, mocking me. I love reading fiction but I’m generally a slow reader and try to get around to writers I haven’t read yet, so I often will do the “big hits” of someone and then move on. I need to do more Pynchon, though.

ABR: Mason & Dixon is my favorite Pynchon novel—which makes me something of a heretic around these parts. I couldn’t recommend it more highly, and I think you’ll enjoy the mechanical duck.

SR: I’ll have to give it a try! At this point I’ve come to respect your opinion thoroughly, especially because of your interest in my music, and your Devo artifacts.

ABR: I see what you did there… Ok, I have a few questions from Christian Hänggi, the fellow who literally wrote the book about Pynchon and music! (Pynchon’s Sound of Music, Diaphanes, 2020.) “How do you decide whether a piece of literature is worth turning into a piece of music? How do you choose out of nearly endless possibilities of compositional techniques the ones that allow you to express that which must be expressed?”

SR: Most of my music grows out of an obsession with something—a painting, a phrase, a paragraph, a pop song, a specific musical idea, etc.—so literature in its various forms is just one sort of thing I might become obsessed with. I guess my gut, or my intuition, is deciding what I think is worth turning into a piece of music as I follow my impulses and allow myself to become obsessed with certain things, including literary objects. I start to imagine how I might translate the essence of the thing into music, and a piece of music results. I’d say the techniques required in each case are different and are dictated by the specific circumstances of the inspiration itself, and then the who/what/when/where/why of the music I’m going to create. Of course, as I’ve mentioned earlier, I have tendencies, habits, patterns, etc., that I fall into again and again, even when I try to transcend them, so I think a close look at how I’ve turned literature into music might find some consistent approaches. A source I always cite to describe my creative process is the poem “Why I Am Not a Painter” by Frank O’Hara… for what it’s worth.

ABR: The ending of that poem cracks me up—it’s just perfect. Here’s another question from Christian: “Looking back, have you made any choices you regret? Perhaps the translation between the two media was too literal, or conversely too far-fetched? And related, has rereading or deeper reading a work or author triggered new meanings or inspirations that made you question earlier compositional choices?”

SR: I hate to disappoint Christian, but I don’t look back that much! Once a piece is finished and performed I might revise it a bit to deal with any immediate concerns or problems, but then I usually move on to the next project. As I’ve already said, I don’t reread a whole lot, except perhaps poetry or shorter things, so honestly I don’t think I’ll read Gravity’s Rainbow again and fret over whether I got the inspiration or translation right for my two GR-inspired pieces. I do like thinking of what I’m doing by transforming literary (or other) inspirations into music as translation, which is more an art than a science. In the words of the Pretenders, “Something is lost, but something is found.”

I think Christian is right to mention the idea of being “too literal”—I think about that a lot and notice it in students I work with, trying to translate ideas from one medium to another. Exact examples escape me but I’m sure there are moments in some of my literary-inspired works that represent too-literal thinking. And then there are other moments where I probably missed the point or the depth of a literary idea. But it’s in the nature of the process. I have a short work for solo piano called Stilling which is based on a poem of that name by Donald Revell. There’s a line in the poem that reads, “These are the partial genocides deeply uncompensated.” My short piano piece tried for many things, but I doubt it will ever get to the depth of that line.

ABR: I hadn’t read “Stilling” before, so thank you for pointing it out. It’s a beautiful poem, deeply affecting; but also very mysterious. I need to explore Revell more.

SR: Yeah, Donald Revell’s a great poet. I first heard him at a poetry reading at a quirky SLC gallery called the Art Barn shortly after starting my PhD in 1995. I went up to him afterward and found out he was faculty in the University of Utah English Department and was then also introduced to a grad student working with him named Martin Corless-Smith, a British poet. I ended up having some nice chats with both from time to time, even recorded them speaking/singing some strange lines Revell had pulled from Thoreau; I think with the idea of turning it into a sort of musique concrète piece.

ABR: You eventually did work with Martin Corless-Smith…

SR: I worked closely with Martin on my dissertation composition—a song cycle that set four of his poems called Leave Song. As a precursor to that piece, I recorded myself and a couple other vocalists speaking Martin’s poem “Sounded along dove dōve” and created a musique concrète piece out of that material that’s on my New Focus Recordings 2015 release Young American Inventions.

ABR: Let’s shift gears and talk about your development as a composer. So there’s this teenage trombone player, listening to New Wave and re-inventing “It’s Gonna Rain” with Kraftwerk… When did more formal electronic compositions begin—Brigham Young University?

SR: When I did my undergrad at BYU, 1987–93, electronic music instruction was in its early stages. There was a studio that had a DX7 and a computer (Mac?) with SMPTE tracks (?), and I remember creating a piece as a final project that has evaporated into the digital ether which is just as well—I think I messed with the confusing DX7 algorithms a bit to slightly tweak some of the preset sounds and did my best to understand how the MIDI worked to record a sort of layered performance of the thing, blah blah. It wasn’t very good.

ABR: You earned your Bachelor of Music at BYU. What was next?

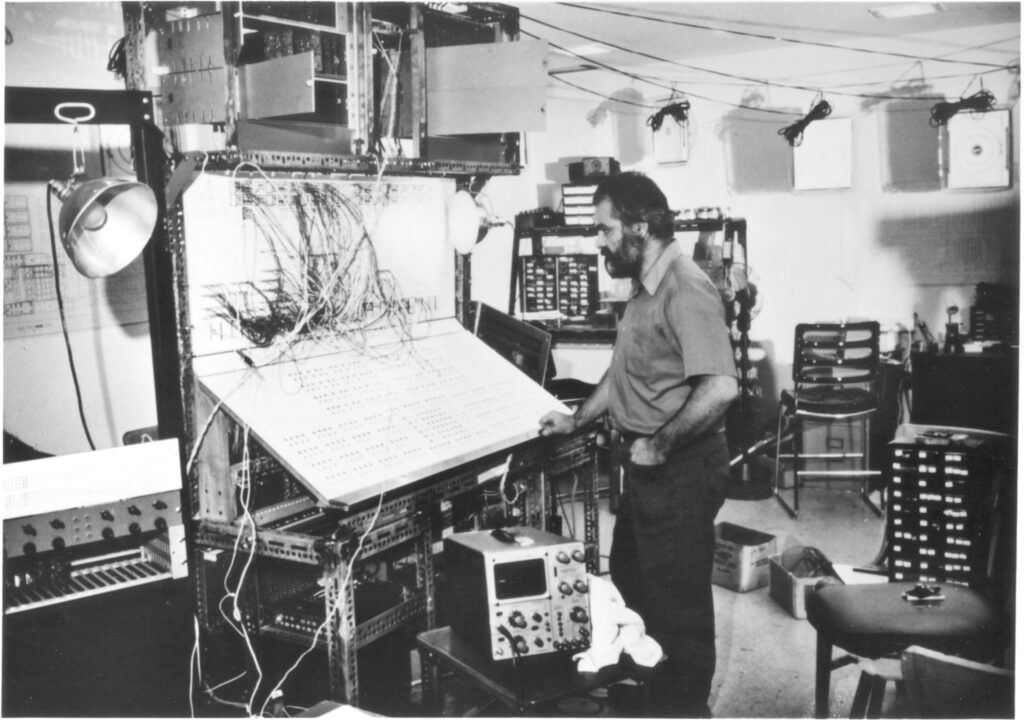

SR: I went to the University of Illinois for my master’s in music composition and spent a lot of time during my two years there, 1993–95, in what’s known as the Experimental Music Studios—several studios that included some old-school synths and reel-to-reel tape decks, a large Buchla synth, and a computer with Sound Designer II (precursor to Pro Tools for digital audio manipulation). I went through a whole regime there of working with analog tape, recording both found sounds and synthesized sounds onto tape and then manipulating and combining said sounds using traditional tape music techniques like cutting and splicing, looping, reversal, tape delay, and speed changing (thus affecting pitch and length, etc.). I worked mainly with Scott Wyatt, director of those studios for years, and it was a great education and foundation in musique concrète and all the approaches, aesthetics, etc. involved with that art form.

ABR: Did you have any other influences beyond Wyatt?

SR: I studied composition for a semester with Salvatore Martirano, himself a noted pioneer in electronic music and who was still exploring things and performing with real-time electronics and improvisation, but I never really talked electronic music with him, regrettably…

ABR: I feel Martirano deserves wider recognition. His L’s GA for Gassed-Masked Politico, Helium Bomb, and Two Channel Tape has the best name for a piece of avant-garde music, ever! I first came across it on a mix-tape called War Pigs, some cassette full of “dark protest songs.” Hearing L’s GA between Black Sabbath and Penderecki’s Threnody was—well, my teenage mind was blown. Martirano seems like a fascinating figure.

SR: L’s GA was performed live at a Martirano retrospective concert I attended my second year at Illinois, sometime in 1994–95. You’re right, an amazing piece, very adventurous and edgy, even then. A great memory from my time there. Two of my composition teachers at BYU were Illinois alumni and told me various stories about him that made him seem intimidating and unapproachable. I think by the time I was there he had calmed down a bit… maybe is one way to say it?

Another memory I have regarding Martirano was being at his house one evening for a hang-out with several other comp students—Sal played an old piece of his from the ‘60s that was all sort of quick cuts, in-your-face saw waves and white noise, etc., that had originally been diffused through some crazy multi-channel system with speakers on the ceiling and surrounding the audience. We all loved it—the gritty, aggressive nature of it seemed to hold up and speak to us. Then he demonstrated his current obsession—improvising on a MIDI keyboard and then the computer listening to his playing and creating some real-time accompaniment through multiple synth banks that were essentially MIDI orchestras, I think using the FORTH programming language to create this interactive environment. I just remember our general response (all us students) was less interest in the result because of the out-of-the-box MIDI sounds. Whatever interesting notes and rhythms Sal or his system were putting out, the preset MIDI sounds had so much baggage and negative associations for us that it just seemed less interesting. I’m sure I’d be a more gracious listener now, for lots of reasons.

ABR: I can understand that. Some of those early MIDI sounds were… well, they haven’t aged well. What came after Illinois?

SR: When I showed up to the University of Utah in fall 1995, the studio there was in an interesting and loose state. Electronic music pioneer Vladimir Ussachevsky had spent the final years of his career there and so his picture was on the wall and his vibe and legacy was in the air, but the studio itself was directed by a guy named Tracy Petersen—an innovator in ways and a former student of Ussachevsky’s, but someone who seemed to be on the outside of the department and University. He was an adjunct instructor and clearly felt disenfranchised, and for better or worse didn’t seem to have much of a strong aesthetic or vision for what was going on in the studio.

I had access to my then-beloved Sound Designer II software, and started dabbling with some of the other equipment in the studio, but the only real electronic piece I created during my studies there was the spoken-word concrète piece based on the poem “Sounded along dove dōve” by Martin Corless-Smith that I mentioned previously. At the same time, my primary composition teacher at the U of U and dissertation advisor was Morris Rosenzweig, a great composer who occasionally created electronic works, and former student of Mario Davidovsky. I was quickly introduced to Davidovsky’s work, and his Synchronisms for various solo/chamber instruments and “tape” have been very influential on my approach to writing music for instruments and electronics. Rosenzweig had established a successful visiting composer program there at the University of Utah and hosted Davidovsky during my first year, in spring of 1996, including a concert that featured Davidovsky’s Pulitzer Prize-winning piece, Synchronisms No. 6 for Piano and Electronic Sounds, so I got a close look at that piece and a chance to hear Davidovsky talk about his early days in the Columbia-Princeton studio and his thoughts about electronic music up close and personal.

ABR: Anything you’d like to share about Davidovsky’s talk?

SR: I remember him describing the two speakers that would output electronic music as “windows to _____” (?) the word I want to put there is “hell,” but not sure I’m remembering that right—maybe it was “the abyss” or something else. Anyway, it was the notion that this medium opened up portals into the unknown where there were endless possibilities. I ended up attending the California State University Summer Arts Program: Composition Seminar the following summer in 1996, and it turned out that Davidovsky was one of the featured senior composers. That double dose of Davidovsky was influential on me in many ways, including my decision to focus the written portion of my dissertation on a close analysis of his piece Quartetto (1987).

ABR: When did you begin to consider yourself an electroacoustic composer?

SR: I was fortunate to get a Visiting Assistant Professor position at BYU in 2001, just after finishing my PhD at the University of Utah, which turned into a permanent position the following year—responsibilities included directing the electronic music studio, which (perhaps obviously!) inspired more concerted efforts to create music that included electronics, in one form or another. At that point I felt like I had a good foundation and a knack for the medium; but I hadn’t as yet created much work I considered complete or mature and didn’t have a single piece in my portfolio that combined live instruments with electronics!

The first piece I created in this vein was Boundless Light (2003) for flute and electronics, and several others followed, many of them on my Mild Violence CD. I’d say all these pieces are heavily influenced by a “Davidovskyan” approach to the medium, which attempts to “imbed the electronic space in the acoustical space” of the instruments involved, and vice versa. I hope I was able in those pieces and in all the work I’ve created since to add my own stamp or approach or flavor, however you want to say it, to the medium—so while my work is absolutely indebted to Davidovsky and many others, I hope my own voice emerges and that the works aren’t simply derivative.

ABR: You studied with Sir Harrison Birtwistle. What was that like?

SR: Birtwistle was an Abravanel Visiting Distinguished Composer at the University of Utah in April of 1998, a guest of the series my teacher Morris had established years earlier. As Morris’s assistant to the series and the Canyonlands New Music Ensemble I had the pleasure of providing rides for Birtwistle and his wife Sheila from their hotel to rehearsals, to finish up payment paperwork, to take them to the mall to buy “American T-shirts,” etc.

ABR: That’s great—“American T-shirts!” The British never disappoint at being British.

SR: At one point he asked me “how I got along with the Mormons?” Of course I had to confess I was one of them, so I got along OK. It was fun getting to know him better that way before meeting with him in a private lesson. I played a recent work for him I had conducted with student performers earlier that year—Circulation Segment—which I think he thought was fine but didn’t seem particularly impressed by it or anything. I had already been thinking of studying abroad at that point, and my wife Laura’s father was born in Bradford, England, so looking for opportunities in the UK seemed like a good fit.

By fall 1998 Laura and I were newly married and getting excited about the idea of living abroad for a while. I got Birtwistle’s number from Morris and worked up the courage to call it one Saturday, at a time I figured was good after being sure I had the time differences right. Birtwistle answered, was friendly, and explained that he’d be at King’s College London for the foreseeable future and if I got in there or came there or whatever, I could work with him. I asked if he would write me a letter for grant/fellowship applications, and he said sure, just contact his agent, and gave me said agent’s number. We were in business. I found out King’s College London had a one-year certificate course called the Certificate in Advanced Musical Studies (perfect) so planned to apply to that and to start applying for grants or fellowships to help support a year in London.

I called Birtwistle’s agent sometime after that, and a few weeks later, sure enough, a letter of recommendation showed up—probably the shortest, most hilarious such letter I’ve ever received that said, “I believe Steven Ricks is a talented composer who could benefit from spending some time outside of Utah.” GLOWING! I might even be exaggerating to add the word “talented” to the letter—I should check that. Maybe that’s why I didn’t get a Fulbright. But I was successful in getting a graduate research fellowship from the University of Utah, and that, combined with our savings, made it possible for us to head to London for a year and be relatively responsibility-free except for me studying composition and both of us making the most of living in central London.

I met with Birtwistle once every two weeks pretty consistently that whole academic year, which included a fun excursion to the National Gallery with him and his former student Ross Lorraine when a rehearsal for Gawain at Covent Garden we were supposed to attend got canceled. I remember in particular heading to Piero della Francesca’s The Nativity and him commenting on the mouth positions of the singers and donkey in the background. I also interviewed Birtwistle about his opera The Last Supper, written for Daniel Barenboim and the Staatsoper Berlin and premiered that year—one of the memorable Birtwistle performances and travel excursions from the year as well. I kept asking for the interview, and near the end of our stay in London he invited me to his house where I went, somehow passed a quiz on fresh herbs from his garden, was fed some amazing chicken he prepared, and interviewed him. I ended up publishing the interview in a Society of Composers, Inc. newsletter—not sure it’s that insightful or even available, but it was certainly a fun experience.

ABR: In fact, the interview is available online as a PDF through the SCI site. How did Sir Harrison impact your compositional style?

SR: The two primary pieces I composed while working with Sir Harrison were Leave Song, the song cycle that became my dissertation piece, and the solo version of Dividing Time for multiple non-pitched percussion instruments. The four poems I set in Leave Song were by Martin Corless-Smith, the British poet I mentioned previously. I introduced him to Birtwistle during his Utah visit and I think they got on well. I remember one of the first things Birtwistle said when I showed up to study with him was “I like your poet.” I think they had some interaction past Birtwistle’s visit and obviously Martin’s British-ness, which infused his poetry, connected with Sir Harrison. The poems reminded Birtwistle of “Ariel’s songs from The Tempest,” and that play and description and theatrical thinking in general really influenced my creation of that piece. It was a great vehicle for me to see how the theater and theatrical elements influenced Birtwistle’s work and approach, which I then of course observed and studied in so many of his pieces, not just the operas.

For the percussion solo, Birtwistle had a ton of tricks up his sleeve regarding the use of patterns and how a background figure could morph into a foreground element—a bunch of which he quickly sketched out on a page and which I still use to this day. He said “it’s the sort of piece you can write in an afternoon.” It took me longer than that, but I came to understand what he meant: the idea that you could have some systems, or mechanisms, or patterns you choose to use and just set to it and get it done. At another point in studying with him he asked if I composed “off the top of my head,” which I probably said I did, or at least partially did, and to which he said something like “the last time I composed a piece off the top of my head was 1956.” Or something like that.

ABR: Ha ha! Of course.

SR: Anyway, it was a great year for lots of reasons. Working with Birtwistle was definitely influential, but so was attending every new music concert I could manage, and it was a busy year thanks to the approaching and then newly arrived millennium, so there were portrait concerts of Berio, Boulez, and Stockhausen, with all of them in attendance and speaking, and then Boulez conducting the London Phil with premieres of new commissions by Péter Eötvös, Salvatore Sciarrino, and others, not to mention all the chamber and solo stuff happening, regular concerts by the London Sinfonietta, the list goes on. I’d say all the music I heard and theater and art I saw that year is still paying dividends.

ABR: That sounds like a wonderful experience! And going back to our topic of intimidating bookshelves, I should mention that James Joyce’s Ulysses was an influence on Pierre Boulez and Luciano Berio, and Thomas Pynchon himself discusses Karlheinz Stockhausen in The Crying of Lot 49. In fact, “Pynchon On Record” has a few composers citing both Stockhausen and Pynchon as influences: Tim Souster, Cort Lippe, Claus-Steffan Mahnkopf.

SR: They did Stockhausen’s Gruppen at the South Bank Centre in that portrait concert I mentioned above, and then ALL the Klavierstücke… they played Gruppen twice and invited everyone to switch places for the second performance. And yes, Ulysses… it’s probably there on the shelf next to Infinite Jest. I spent a lot of time with Berio’s Thema (Omaggio a Joyce) in the years prior to going to England, which is based on a passage from Ulysses, and that little piece I’ve mentioned (Sounded along dove dōve) is heavily inspired by it. Still haven’t read Ulysses (!) but I think I understood it (whether this is accurate or not) as an important precursor to GR.

ABR: I would certainly agree to that, and they are frequently mentioned in the same breath. Last question. Some visitors coming to this page from the literary side may not be familiar with your music; while visitors arriving as Steve Ricks fans may not be familiar with Pynchon. Do you have any musical recommendations for the first group, and any literary recommendations for the second?

SR: In general, I always hope people keep an open mind, and I would typically fine-tune my musical recommendations to the individual, perhaps like a doctor giving a prescription (I am a doctor of music, after all). So, giving a general recommendation is perhaps challenging, but here are a few. First, here’s a listening list with two works each by five composers who have all had an impact on me, and whose work represents some of the things I love most about contemporary music:

Mario Davidovsky: Quartetto (1987), Synchronisms No. 10 (1995)

Morris Rosenzweig: Points and Tales (2004), Rough Sleepers (2008)

Steve Reich: Music for 18 Musicians (1974-76), Eight Lines (Octet) (1979)

Harrison Birtwistle: Carmen Arcadiae Mechanicae Perpetuum (1977-78), Pulse Shadows (1989-96)

Michael Hicks: Sacral Segments, (1992) Rain Tiger (2002)

An additional list of composers who have had an impact on me in more recent years and whose work I admire would include: Ned McGowan, Scott Miller, Kurt Rohde, David Sanford, and Carla Scaletti—apologies to others I haven’t included here but I think a search and deeper dive into the works of these composers is well worth the time.

I’ve been fortunate to have great colleagues here at BYU through the years, and the music of Christian Asplund has been influential and inspirational in many ways, not least of which through our ongoing improvising duo RICKSPLUND, that features Asplund on viola, piano, and occasionally electronic keyboards/devices, and me on trombone and/or laptop.

I love all sorts of music and am inspired by all of it. I think you can hear influences from jazz, rock, and older classical music in all my works, but my obsessions for specific pieces bring out different emphases. I’m happy to recommend folks listen to John Coltrane, and then any number of popular singers/bands like Talking Heads, Kate Bush, Radiohead, and the Pixies. Those last four bands are all specifically influential on my piece Anthology and are among my favorites.

For literary recommendations, I wouldn’t quite know what to say. As we’ve discussed, I do love Vonnegut and I particularly love his technique of summarizing his(?) or Kilgore Trout’s short stories in his novels. It gives me the strange experience after having read something like Timequake of feeling like I’ve also read a bunch of different short stories… like the sum is greater than the parts of all the words on the pages… it’s more than just a single novel.

ABR: Thank you, Steve, for your thoughtful, detailed, and engaging responses. I look forward to reviewing Captain Blicero’s House of Fun!

SR: Oh man… I think I’ll leave that opera for someone else. Maybe I’ll create one or two more Pynchon-inspired works once I read more. Thanks so much—this was a blast!

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Posted: 15 February 2022

Last Modified: 17 June 2022

Return to: Steve Ricks Page

Return to: Pynchonalia

Explore: Pynchon On Record

Main Pynchon Page: Spermatikos Logos

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com

Posted: 15 February 2022

Last Modified: 17 June 2022

Return to: Steve Ricks Page

Return to: Pynchonalia

Explore: Pynchon On Record

Main Pynchon Page: Spermatikos Logos

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com