Interview with Tris McCall

- At December 29, 2021

- By Great Quail

- In Pynchon, The Modern Word

0

0

A Conversation with Tris McCall

Tris McCall & Color Out of Space

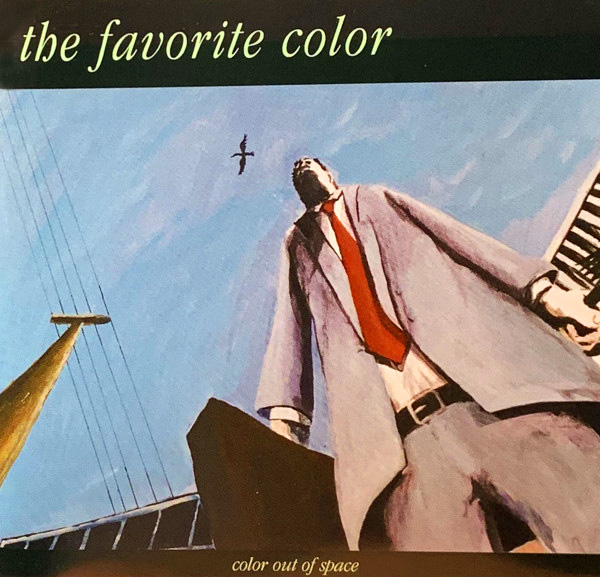

Tris McCall is a musician, novelist, and rock journalist from New Jersey. In 1996, his band the Favorite Color released their only full-length album, Color Out of Space. Featuring the song “V. In Love,” a setting of Thomas Pynchon’s “The Eyes of a New York Woman,” the album has been featured on the Modern Word’s Spermatikos Logos since 1997. Although the Favorite Color was short-lived, Tris McCall has released numerous solo albums, each an insightful lyrical meditation on urban development, industrial decay, and the effects they have on neighborhoods, cultures, and lives. Brooklyn Rail put it best: “McCall doesn’t sing about Bruce Springsteen’s boardwalks, arcades, and cheap little seaside bars … Rather, he provides an alternative New Jersey mythology, which is more urban, urbane, and ironic.” McCall has also published a novel called The Trespassers, maintains the Tris McCall Report, an active blog about music and politics, and is currently working on Almanac, an interactive album of songs and stories based on his travels across the United States.

On the 25th anniversary of Color Out of Space, Allen Ruch of the Modern Word caught up with Tris McCall to discuss the album, its connection to Thomas Pynchon, and the influence of literature in McCall’s more recent work.

Interview

The Modern Word: First of all, congratulations on the 25th anniversary of Color Out of Space! I remember featuring this album on “Pynchon On Record” shortly after it first came out—I believe Dr. Daw was in contact with you, back when Vineland was still Pynchon’s latest novel. It’s a great record, and it’s nice to feature it a little more fully on the revised site. Listening to it again, it really brought back memories of the ‘90s, back when I was struggling pretty hard to actually like Lotion! But Color really holds up, and it’s nice to see some of the songs have renewed life on your solo albums.

Tris McCall: On behalf of the people involved in that project—Steven Matrick, Tom Snow, Marty Urciuoli, David Schreiber, and producers Tim Hatfield and Bill Stair—I’d like to thank you for listening. It wasn’t widely circulated, but I do think that those who heard Color Out of Space enjoyed it. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that we lost David a few short weeks ago. He spent most of his adult life battling illnesses. Twenty five years is a long time to fight.

TMW: I am sorry to hear that.

Tris McCall: It was no secret that his guitar playing was my favorite thing about the Favorite Color. David had so much to do with the character of that album, and his musical intelligence was my guide for many years after that.

TMW: The whole album is satisfyingly tight, and it’s clear you were comfortable playing with each other. David Schreiber had a great sound, and his chemistry with Steven Matrick in particular really shines! So let’s talk more about the album. Color Out of Space features several literary allusions besides Pynchon, from its Lovecraftian title to the track “Valis,” inspired by Philip K. Dick. Does this album represent a snapshot of your reading at the time? Or is it the culmination of numerous influences?

Tris McCall: It’s a snapshot of my reading at the time. I was working at a quick consultancy in Chelsea—the sort of job that has been obliterated by the Internet. Corporate clients, some of whom turned out to be military-industrial contractors, would call with the kind of question that could now be answered with a five second search engine inquiry. It was 1995 and Google hadn’t even been launched. I was on retainer and was expected to answer scores of questions every day: what was the difference between this kind of bolt and that kind of screw, how much money did Raytheon spend on manufacturing a certain missile, how much weapons-grade steel did Japan export in 1970, etc. This was my first exposure to the world of business in New York City, and I found it all dizzying and humbling and borderline absurd. So I was drawn to literature that made fun of corporations and corporate culture, including J R by William Gaddis, which was a big influence on the writing on Color Out of Space (even though I didn’t name-check Gaddis in a song until ‘99). Donald Barthelme’s short stories helped, and so did Philip K. Dick, who was an astute corporate satirist when he wanted to be. The portrayal of Yoyodyne in V. and The Crying of Lot 49 seemed right on the money to me. That got me through a few of those long days in the library of corporate annual reports (there was a huge library of annual reports).

TMW: Now that you mention it, I can sense J R in that album for sure. There’s a clear interest in the flow of wealth. I think it’s a shame more people don’t read Gaddis; The Recognitions is a lot of fun; yet very heartbreaking, too. So, what song of yours “namechecked” Gaddis?

Tris McCall: It’s a two-chord stomper called “Mad About Us.” William Gaddis, urbane as he was, would have disliked it. But there’s another song on that same album—If One of These Bottles Should Happen to Fall—that’s directly influenced by J R. It’s called “Hung by a Jury of My Peers,” and it’s another expression of bewilderment with corporate New York as I experienced it in the 1990s. Thematically, it’s a leftover from Color Out of Space, and it’s definitely Gaddis-influenced.

The observation in J R is that American capitalism has deliberately been optimized for eleven-year-olds and people with eleven-year-old mentalities. Eleven-year-olds aren’t dumb, but they are prepubescent: their drives aren’t sexual drives. J R Vansant, and the thousands of grown-up J R Vansants who dominate American boardrooms, haven’t reached sexual maturity and likely never will. That makes them natural adversaries for pop musicians, because pop is an unvarnished expression of adolescent urges. As an arrested adolescent myself, I felt Gaddis’s critique—though I regret to say that I put it much more crudely than he did.

TMW: Pynchon didn’t just inspire a song on Color; you actually set the lyrics to “The Eyes of a New York Woman” to music. Pynchon has dozens of lyrics to fictional songs. Why that particular song? What was it you found appealing?

Tris McCall: I remember working on a bunch of them all at once, mostly on the 123 bus from Manhattan to Union City. I set the last Paranoids song in Crying of Lot 49 to music; I don’t recall how that went, but I’m pretty sure I biffed it. “Esther’s Nose Job”—that one implied a particular melody and arrangement. “White Man Welcome to Puke-a-hook-a-lookie Island”—I tried to get the band to play that with me, but they wouldn’t hear of it; I believe wiser heads prevailed there. “The Eyes of a New York Woman” was probably the most normal-sounding lyric of the bunch, and it was the one that inspired the nicest melody, so that’s the one that ended up in the repertoire. The extreme periphery of our repertoire, mind you, but that wasn’t my doing—I liked it!

TMW: I like it, too—“dead as the graveyard sea” is a great image. And speaking of particular arrangements, “Esther’s Nose Job” now makes me think of Soft Machine more than Pynchon!

Tris McCall: Me, too. I think of Soft Machine and Thomas Pynchon both. They go nicely together, no? Sometimes I forget that Gravity’s Rainbow was written at the height of the progressive rock movement. If you told me you were into Pynchon and the Canterbury scene and stuff like Caravan, that’d make perfect sense. It’s not just the ambition and thematic depth. It’s the formal experimentation, and the capacity to stay playful while peeking into the void. There’s a feeling of unlimited horizons and constant surprise—the artist is taking you on a wild trip, and you’re expected to hang on and handle the curves as they come. No fanservice, you know? If you’re on this ride, you’re expected to pay your way. Topographic Oceans, The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway, Crimson’s Red was right around the corner. There were similar creative aspirations in visual arts, too—the men and women involved in Tropicalía, for instance, were looking to shake any palm tree they could shake. People were really going for it. It must have been an exciting time.

TMW: Okay, here’s a real geeky question: Was there any reason you called it “V. In Love,” an allusion that occurs later in the novel?

Tris McCall: The sadly-not-too-geeky answer is that it was a lame bit of subterfuge on my part. I wanted the song on the album, but our producers didn’t like it at all. They heard us play it at a show—it was hardly ever played—and singled it out for opprobrium. They were enthusiastic about most of our stuff, but they were scathing about “The Eyes of a New York Woman.” My girlfriend didn’t like it, either; she thought it reeked of mid-sixties sexism. Even my father, who usually had no opinion about my writing at all, told me it was bad. I didn’t understand: it was Thomas Pynchon! It had to be good. I radically re-arranged the song and wrote “V. In Love” on the reel so they wouldn’t think we were spending time on something they’d already rejected. Once it was done, I whined and whined and whined until they acquiesced and agreed to mix it. I wish we’d stuck with the original version, which was arranged like Hüsker Dü—all ringing open chords and pre-amp distortion and me hollering over the top, trying to get into that Benny Profane spirit.

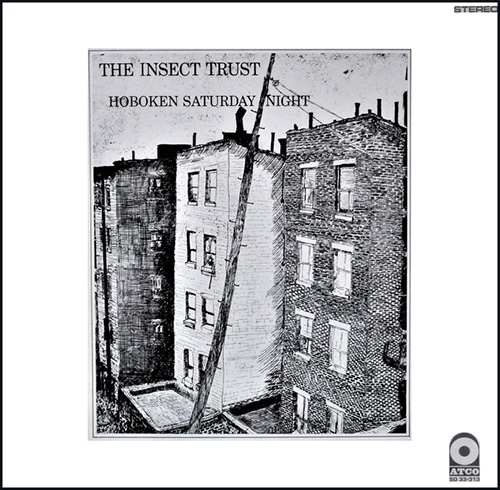

TMW: I’m sure there’s a whole book to be written about how musicians have tricked their labels! But I agree, the song seems much better adapted to a traditional arrangement than, say, “White Man Welcome to Puke-a-hook-a-lookie Island!” Another New Jersey group, The Insect Trust, recorded their own version of “The Eyes of a New York Woman” in the late 1960s, and were sued by Pynchon. They later sought, and received permission; the track appeared on 1970s Hoboken Saturday Night. Were you aware of their version when you recorded your own song? And if so, did it have any influence on you—artistic or, shall we say, legal?

Tris McCall: I would’ve been crushed if I’d been sued by Thomas Pynchon. I was 24 and naïve about publishing as a vocation: I thought, hey, he wrote these lyrics, why wouldn’t he want some idiot kid from New Jersey setting them to music? We could be pals! If the album had been made for a major label, I’m sure we all would have gotten colorful-terrifying letters from lawyers. As it was, I didn’t find out about the Insect Trust until Color Out of Space was already out, and then I felt pretty dumb: of all the Pynchon lyrics in all the pages of his books, I had to go and choose one that some other guys had already picked. I felt doubly bad that the band was from Hoboken, because it suggested that I didn’t know their album (and I didn’t), and I’d tried to represent myself as a scholar of Jersey musical history. That was a major part of my schtick. I guess it still is.

TMW: To be fair, it was pretty obscure even in its time. It’s a nice version, though, and Hoboken Saturday Night is due for a deluxe reissue.

Tris McCall: The tenements pictured on the album cover are ten minutes by bicycle from our apartment. I should have known about it. No excuses! Plus it’s a very modern-sounding album, isn’t it? It was cut in 1970, but some of those songs play like wordy mid-‘00s folk-pop, complete with woodwind squalls. I like Nancy Jefferies’s austere post-Airplane singing style, too; I think it suits Pynchon much better than my weedy proletarian vocals. I don’t know what writer my voice goes with. I guess Philip Roth is the obvious answer, given where I’m from and what I write about, but Philip Roth never gave us a “Ballad of Tantivy Mucker-Maffick.”

TMW: Are you still reading Thomas Pynchon? Any thoughts about his work since Vineland?

Tris McCall: I remain a fan, and I continue to associate his music with pop-rock. I read most of Against the Day in a tour van with a band called Kapow! I really liked Mason & Dixon—that was a fun ride. I probably think about that one more than any of the others.

TMW: It’s my favorite. I know we’re in the minority here, borderline heresy; but I like it better than Gravity’s Rainbow.

Tris McCall: Sometimes Pynchon is called difficult, and I don’t get that at all. A writer like Gaddis, or Virginia Woolf, or Henry James is hard to read: the writing is so dense, and the worldview is so upsetting that you’ve kinda got to swim to the far shore of the book to catch your breath and appreciate it. It’s a retrospective pleasure. While you’re in the midst of it, it just hurts. Pynchon, by contrast, is a waterslide. You’re going fast, and things are hurtling by, it’s hard to grasp anything firm, but that’s G, because you’re splashing around in the sentences and speeding downhill and achieving weightlessness. It’s worth it for the g-forces alone. In my experience, I’m often laughing too hard to have anything other than a good time.

TMW: That’s a great description! Let’s talk about your music after Favorite Color. Your solo work has been praised for its wit, its political acumen, and its dedication to your home state of New Jersey. You have been compared to Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, two very narrative songwriters. How does your passion for literature inform your songwriting? Are there any writers you find particularly influential on your songwriting, whether on past or current work?

Tris McCall: Anybody who compares me to the Boss is being very kind to me. Just about everybody who makes music in New Jersey is influenced by Springsteen on some level, but yes, I have gone out of my way to do that kind of recursive, intertextual storytelling I associate with the Nebraska and Born in the U.S.A. albums. Springsteen is very good at writing characters. And I’ve got to admit—although I’m always reading something, the stories and characters that stay with me are the ones I’ve encountered on pop albums.

Instinctively, this seems wrong to me. Randy Newman’s Land of Dreams contains a tiny fraction of the words, voices, and characters in Gravity’s Rainbow, a book I loved. Why is Randy’s story so much more present to my thoughts? Why did it penetrate my consciousness and become part of the frame through which I see the world?

TMW: Randy Newman has written some great character songs! Long before his work for Disney. His ability to capture a character with just a few lyrics, even to spoof himself, it’s just great. Music has that ability…

Tris McCall: Why can I “see” the characters on Arthur by the Kinks so much clearer than the ones in The Deer Hunter, especially given that I’ve never seen them at all? After decades of this, I am forced to conclude that this is simply how my funny little noggin works. If you want me to remember something—details and themes, colors, character voices—the surest way to make an impression is by singing it at me.

TMW: Going back to Springsteen’s “recursive, intertextual storytelling,” your project McCall’s Almanac is a voyage across the United States, with each state is represented by its own cartoon, song, and short story. (My favorite story is “Ralph,” by the way.) It’s an ambitious project, with a postmodern structure, in that the user gets to decide the order of songs. Along with the Boss, I can see Sufjan Stevens here and even Tori Amos, with Scarlet’s Walk. Does Almanac have any literary inspirations?

Tris McCall: I continue to love books, and I still write music that’s inspired by the stuff I’ve read. My favorite song/story from the Almanac project—“The Unmapped Man” (New Orleans)—is a direct descendent of The Moviegoer by Walker Percy. It was originally called “Binx Bolling’s Blues,” and then I changed the character in the song and in the story to something a little bit less Southern Gentleman and a little bit more Tris McCall. “Route 52” is definitely an Ursula LeGuin scenario. “You Needn’t Be So Mean, Baby”—that’s a reference to J.D. Salinger. “Take Me to the Waterfall” is a stepchild of Mary Gaitskill. I’m sure there are other, more general, literary sources for the writing I did on the Almanac: Rebecca West’s The Fountain Overflows, Ray Bradbury, Carson McCullers, Philip Roth’s Nemesis, and definitely, definitely Dhalgren, which I think about every day.

The Best Ever Death Metal Band in Madison?

The Best Ever Death Metal Band in Madison?

TMW: What blank states are you most eager to fill in? (BTW: Let’s wish you more luck than Sufjan Stevens in completing your musical journey!)

Tris McCall: It would be a wonderful feeling to get back on the road, wouldn’t it? I think more places in California deserve songs. Oakland deserves its own song; that’s a fascinating place. Asheville needs a song. Santa Fe, New Mexico—there’s a song waiting to happen. Louisville needs a song. I’ve never been to Kansas City, but I’ve heard the architecture is great. Also, I’ve always been a fan of the Royals.

TMW: I’m actually from Allentown, Pennsylvania. You can be the first singer-songwriter to memorialize my town in song! (Oh wait…)

Ok, moving from Route 52 to Highway 61. When Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2016, it was the first time a writer known primarily as a lyricist won that prestigious award. It was also a somewhat controversial decision, given the number of remarkable poets, playwrights, and novelists still unrecognized by the committee. What are your feelings about the decision? And as a lyricist and novelist yourself, did Dylan’s award have any personal meaning for you?

Tris McCall: I guess I felt the same way I did when Kendrick got his Pulitzer: it’s a nice recognition of the power of lyrics, but it’s not strictly necessary. We can all agree that Kendrick’s experiments with narrative on albums like Good Kid, m.A.A.d. City were audacious. That audacity doesn’t have to be ratified by the Pulitzer committee to resonate for listeners. Also, as someone with the highest respect for pop song lyrics and lyricists, Dylan is not where I would have begun. I would have started with Chuck Berry, who chopped the wood and forged the steel that we’ve all been building with ever since. It kinda feels like they jumped into the middle of the story.

TMW: I’m of two minds. I love both Kendrick and Dylan—and find it interesting the Pulitzer committee awarded DAMN. and not To Pimp a Butterfly, seems little late to the party to me—and think they were both certainly deserving, but there’s so many awards for rock and hip hop, and so few prestigious awards for classical music, poetry, and literature. The Pulitzer and the Nobel Prize are the only way some people even hear of certain musicians and writers. But again, it’s Kendrick and Dylan, so… See? Two minds.

Tris McCall: I do understand that. As a person who writes words and songs that are designed to work together, I am painfully aware that it is a thousand times easier to get somebody to listen to the song than it is to get them to read the story. Once can be done passively. The other one can’t. I’m a pop supremacist, so I never mind when the Taylor Swift bandwagon rolls through town. I’d never begrudge her any of her accolades. But word-writers are struggling for oxygen. We want some attention and recognition, too!

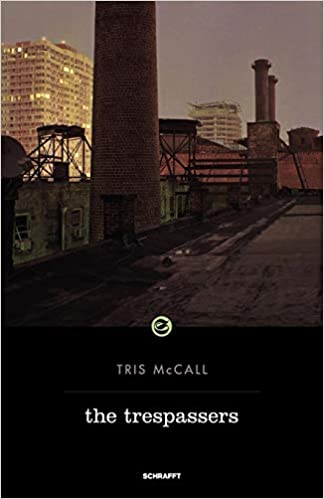

TMW: Your 2012 novel The Trespassers has been described as romance of industrial decay, a love letter to rusting factories. Many of your songs prominently feature abandoned factories, tunnels, turnpikes, strip malls, ferries, traffic jams, and so on. Is it safe to say you are fascinated—if not enamored of—dystopian landscapes? Why is that? Are there any artists you feel share this muse?

Tris McCall: Urban exploration is a pretty big pastime in North Jersey, or it was, anyway, in the ‘00s, before everything was redeveloped. The post-industrial style remains a dominant strain in Hudson County art: reused and repurposed materials, sand and dirt, the beauty of old machinery, creative re-imaginings of factories and warehouses, making sculptures out of PVC pipe and copper wire, resourcefulness, scrappiness, Jersey-ness. The best art show currently on view in Jersey City (“Alive Is a Matter of Opinion” @ SMUSH) is a ribbon of shots of decaying storefronts and speeding trains and rusted-out cars in alleyways. I suppose a day may come when we’re not obsessed with the residue of Hudson County as it once was, but that day is not today.

The Trespassers is the strange star that everything else I’ve ever done orbits around. Everything I’ve ever had to say is in that book, and the rest of my writing—including all the journalism I’ve done—just feels like restatement. What’s odd about that is that the main character and narrator is decidedly not me: I love him, and I hope readers love him, too, but he’s an infuriating kid, and his opinions are not mine. He does not experience post-industrial New Jersey as a dystopia in the slightest; instead, as a budding outlaw and self-styled rebel from North Carolina, he quickly sizes it up as a land of hiding places. He appreciates the abandoned buildings aesthetically, but he also sees Jersey as a place that affords the kind of adventure and escape, and unsupervised mischief, that he’s been craving. He’s sixteen, but he’s a student of history, and while he’s got no illusions about the Civil War or the Confederacy, he’s a sucker for lost causes. I’m sure he suspects that he’s a lost cause himself. There’s a lot of that in New Jersey. It’s one of many, many things we’ve got in common with the South.

TMW: Last question. Some visitors coming to this page from the literary side may not be familiar with your music; while visitors arriving as Tris McCall fans may not be familiar with Pynchon. Do you have any musical recommendations for the first group, and any literary recommendations for the second?

Tris McCall: Do all Pynchon fans appreciate the Fiery Furnaces and Friedberger, Inc. solo albums like Winter Women and Last Summer? I reckon they do. It’s not just the density of allusion. It’s the wordplay and the sense of humor, too—the character voices and conspiracy theories, and the wistful streak running through all of it. I’d advise fans of Pynchon to dip a toe into the Serengeti whirlpool. It’s not that his writing reminds me of Pynchon’s, necessarily. It’s that I think they’d be well disposed to weather the storm of words and characters and digressions and apophenia.

I don’t know whether fans of Thomas Pynchon would enjoy Tris McCall music. I hope they would, and I hope that people who appreciate my music would also like Pynchon. I’m definitely not going to recommend Dhalgren to anybody; that’s madness. But hey: here’s a book that my readers and listeners might like, and one that doesn’t get talked about very often anymore. I consider The Last Hurrah by Edwin O’Connor the most trenchant book ever written about American politics and Northeastern American cities, and that’s because it gets at the tremendous sadness at the heart of civic life. If you’re a Tris McCall listener, you’re probably acquainted with the pain and pathos and of the politician, too, because that’s a big subject of mine—the crushing sadness of the popularity contest, and the corrosive sadness of a country that’s decided to organize its public culture around popularity contests. Missed chances, wasted potential, dissipated energy, it’s as heartbreaking as Hudson County. Emo-politico: that’s the specialty of the house.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Posted: 29 December 2021

Last Modified: 29 December 2021

Return to: Favorite Color Page

Return to: Pynchonalia

Explore: Pynchon On Record

Main Pynchon Page: Spermatikos Logos

Contact:quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com

Posted: 29 December 2021

Last Modified: 29 December 2021

Return to: Favorite Color Page

Return to: Pynchonalia

Explore: Pynchon On Record

Main Pynchon Page: Spermatikos Logos

Contact:quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com