Pynchon Music: Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf, “The Courier’s Tragedy”

The Courier’s Tragedy: Strategies for a Deconstructive Morphology

Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf

From Musical Morphology, Ed. Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf, Frank Cox & Wolfram Schurig. Hofheim: Wolke, 2004. 147-61.

The personal need to react deconstructively to one’s own musical morphology stems from a loss of faith in the usefulness of these morphemes with regard to their musical sense and their function. To dispense entirely with musical morphology—the legacy of motivic-thematic thinking—with its component shapes, severely restricts the field of compositional activity: ultimately, the only option would be pure sound-composition, to whatever degree it might or might not be internally textural (and thus quasi-morphous). Musical shapes that are recognizable as such (i.e., which are not deliberately concealed) can scarcely be avoided. Once this is understood one must address the question of the extent of the shapes’ own internal critique, the matter of how the morphemes’ tendency towards a self-referential identity and a clear sense can be undermined, and thus liquefied—to the necessary degree for their “truth” to be retained. The possible solutions to the dilemma between the necessity of working morphologically and the impossibility of doing so “authentically” will be different in every work. I would therefore prefer to speak of strategies for a deconstructive approach to musical morphology, not of specific techniques in the sense of a system or methodology. This shall be demonstrated by examining a work from my Pynchon-cycle.

The point of departure for the cello solo The Courier’s Tragedy was a twofold one: first of all, Frank Cox, who took my solo La vision d’ange nouveau (1997/8, part of my Angelus Novus cycle) into his repertoire in 2000, proved an ideal performer, being a composer of the same “school” (complexism, deconstruction), who thinks in the very categories that define the piece in its conception and creation. I therefore increasingly desired to write a piece for him, one revolving around his unique way of playing the cello, his fearlessness in the face of any effort or “impossibility”; the new piece would thus be tailor-made, even at the risk that he would initially be its only performer. His credo that “unplayable” works might in fact be more interesting than easily playable ones naturally suited my ideas concerning “deconstructive performance practice” to a tee. The second factor was my projected cycle inspired by the writer Thomas Pynchon, into which I would easily be able to integrate the planned cello piece. The cello piece is thus both a solo work and a constituent of the poly-work Hommage à Thomas Pynchon. It requires scordatura tuning, with the two lowest strings re-tuned by quarter-tones to produce a tritone, and the A-string and the D-string tuned down a major and minor 9th respectively at the start of “Acts” II and III. This ultimately results in a scordatura consisting of two diminished 5ths a quarter-tone apart.

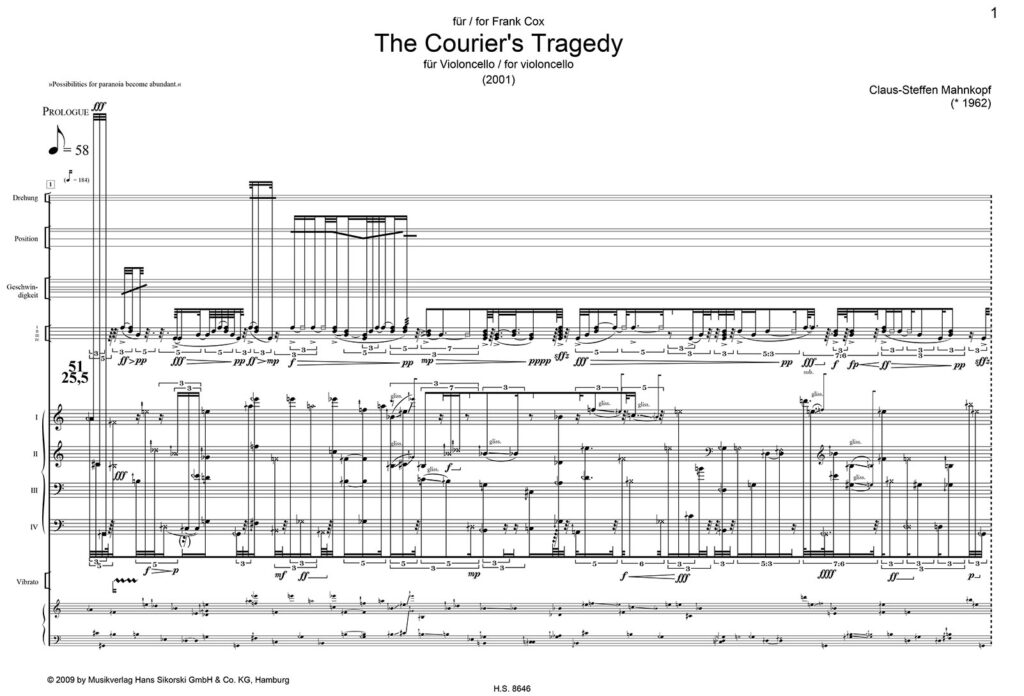

The piece is notated on ten systems (with two additional systems for the sounding pitches, rather like a piano reduction): five for the left hand, five for the right. The left-hand systems correspond to the four strings with precise assignment of positions and fingerings (specifying the fingered pitches, finger- percussion and corresponding dynamics, glissandi and left-hand pizzicato) and vibrato. The right-hand systems have the following functions: a) rotation of the bow between hair and wood, b) bowing-position between molto sul tasto (from “Act IV” onwards also behind the left-hand fingers) and behind the bridge, c) bowing-speed (from molto flautando to three different degrees of “scrunch tone”), d) assignment to the four strings with articulation, dynamics and mode of production (bowed, struck, stopped), and—when required—e) articulation, carried out independently of the assignment to the four strings. All parameters relevant to instrumental practice are thus defined through the notation (I avoided both the verbal notation such as that preferred by Lachenmann and the graphic variety used, for example, by Billone).

The piece has a duration of 19 minutes, one minute longer than the standard length of the main constituents of the Pynchon cycle (The Tristero System, The Courier’s Tragedy, W.A.S.T.E.). As the different acts have divergent amounts of text (and thus differ in their dramaturgical weight) I decided on the following timing: “Prologue” and “Epilogue” both one minute, “Acts” I to III three minutes each, “Act IV” six minutes (part 1 one minute, part 2 four minutes, with an insert of one minute) and “Act V” two minutes.

The manner of compositional production is indeed just that: the process was initially conceived as counter-musical, nonsensical and reified in its strict adherence to the literary model, the fictitious play The Courier’s Tragedy from the shortest of Pynchon’s novels, The Crying of Lot 49. The formal construction, which follows that of the novel, is as follows:

The “Prologue” tells of the murder of the good duke of Faggio at the hands of Angelo, the evil duke of Squamuglia. Musically speaking, this section is characterized by emphatic gestures and virtuosic playing, with an interaction between “normal” playing (with the hands synchronized) and finger-percussion.

“Act I” involves the gruesome death by torture of Domenico. The dominant musical element is the use of “scrunch-tones.” The action in “Act II” consists of torture, and ultimately involves the death of the cardinal, who is forced to consecrate his blood to Satan. What is musically significant here is the de-tuning of the A-string, which effects the first restriction of the instrument’s range and leads to a reduction of the instrument’s sonic presence. In “Act III,” Pasquale is murdered. The music is affected by a further restriction of both range and sonic presence, as the D-string is now also de-tuned. In “Act IV,” where Ercole and Niccolò also die, there is a remarkable change of mood. This section is therefore divided into two sub-sections:

a) There is frequent mention of proper names, these are converted into finger-percussion tremoli and pizzicati, b) From now on with mute (causing a further restriction of sound-presence); the dominant sound is that of col legno bowing behind the left-hand fingers, so “normally fingered” notes are only heard through use of finger-percussion. Inserted into this second sub-section is an account concerning the Lost Guard of Faggio, the corpses of whose 50 members are found in a lake. Its musical illustration is a series of 50 identical Bartók pizzicati, whose simple stupidity is an absolute departure from the piece’s previous language.

“Act V” involves the final blood bath in Squamuglia (in whose course Angelo also dies). Musically: maximum restriction: (almost) exclusively (desperately loud, desperately expressive) arco playing behind the left-hand fingers (paradoxically less “effective” than col legno battuto); all fingered notes therefore occur as finger-percussion, together with the first appearance of left-hand pizzicato.

In the “Epilogue,” Gennaro is the sole survivor. The music consists of sporadic, extremely quiet tapping with the heel of the bow on the strings, behind the fingers and at different points on the instrument’s body between the fingerboard, the sounding-board and the rim; the player ironically performs vibrato-rhythms on a quadruple-stop which, admittedly, does not sound.

The syntax, metric, scheme and tempi correspond to the text: the “Prologue” has 6 sentences, and 6 measures + 2 measures total 8 measures (because the 5th sentence consists of 3 verse lines). The sentences are internally divided according to punctuation (commas in particular). The “Prologue” has 29 such sub-sentences; applied to the duration of a minute. The first sentence has 51 words in 8 sub-groups. The 8 groups produce the number sequence 1-1-4-15-10-3 — 4-13. The pitch material corresponding to the words was then integrated into these internal groups, which amount to syntactical units.

The pitches were also derived—in a positively mechanical fashion—from the novel. The entire text of The Courier’s Tragedy was scanned and searched for errors; it begins: “Angelo, then, evil Duke of Squamuglia, has perhaps ten years before the play’s opening murdered the good Duke of adjoining Faggio, by poisoning the feet on an Image of Saint Narcissus, Bishop of Jerusalem, In the court chapel, which feet the Duke was in the habit of kissing every Sunday Mass.”

The text was converted into a number-chain with internal codes for punctuation and spaces. During the compositional process, pitches are assigned to these numbers. This leads to a statistically-regulated harmonic disposition with more and less frequent pitches in fixed registers. The piece thus gains, despite the rather chaotic sequence of pitches—i.e., their musically senseless assignment—a form of tonal center, a harmonic identity. The Pynchon text, now a number chain, is read in number-pairs. The first number corresponds to the main pitch of the disposition, the second to its microtonal transposition according to the following scheme. [Omitted]

This pitch-generation was applied initially only to the left hand, regardless of what the right hand, which was composed later, would do. The pitches were connected—according to their feasibility on the cello—to form musical “shapes;” their rhythms, string-distribution, mode of production (also glissando and trill), certain modifications (permutations, multiple-stops), and in some cases their polyphony—all this was decided at the fingerboard, and thus with an almost arbitrary personal freedom.

[An example] shows the concrete form this takes on in the first measure. “Angelo,” being a proper name (see below), is pizzicato; “then” appears as a double-stop (because of its “sympathetic” interval), initially as finger-percussion, then bowed as an arpeggio from the 1st to the 3rd string, joining the first note of “evil” to this mini-phrase; the second note is joined with “Duke” as a finger-percussion phrase; its final note is bowed, directly before “of” appears as a hammer-on; “evil-Duke-of” is thus unified through the use of finger-percussion and a common dynamic (diminuendo).

Absurdly enough, the work contains strong motivic threads. Alongside the two names of the warring duchies (Squamuglia and Faggio), those of all characters occur repeatedly. They are:

Angelo, evil Duke of Squamuglia, responsible for the Duke of Faggio’s death;

Pasquale, the illegitimate son and initial ruler of Faggio;

Niccolò, the rightful heir of Faggio, who is still a minor;

Ercole, a page in Squamuglia, who admittedly sympathizes with Faggio;

Domenico, a “friend” of Niccolò who wishes to betray him, but is murdered by Ercole;

Francesca, sister of Angelo and mother of Pasquale, who is to marry the latter for political reasons

Vittorio, a courier and compatriot of Niccolò, as well as

Gennaro, the self-proclaimed interim ruler of Faggio.

As repeated pitch-sequences take on a motivic character, I decided—as a rule—to emphasize these names through use of pizzicato (despite the ease with which, using the various deconstructive techniques of this piece [see below], this motivic identity could have been undermined, even destroyed). These name- related motifs are varied each time, so that their motivic identity is substantially impaired. This has the dialectical consequence, however, that the pizzicato elements as such, because they so obviously differ from the other sounds (cello pizzicato being like a second instrument), take on a motivic character more significant than that of the actual nominally-defined pitch-sequences themselves.

Deconstructive effects of the morphemes’ “internal critique” already result from the notation, which specifies not so much the sound-result as its production. In the case of finger-percussion—this is particularly familiar on the guitar—two pitches of unequal dynamic sound according to where the string is divided. The “unwanted” (because unnotated) pitch can be damped with the hand or the chin if necessary, but this is not always feasible, particularly at high speed or in the case of complex fingerings. A percussive finger-action on a string that is simultaneously being muted by the bow (by remaining on the string) will not simply produce two pitches; the notated pitch will in fact not sound, as the lower portion of the string is muted by the bow. Such paradoxical situations result from this approach and are desired (and could, furthermore, not be conveyed through a purely result-oriented notation).

The “genuine” deconstructive derformations of the motivic structure are those which were actively composed. Their point of departure is the strict notational separation of the left and right hands, which only synchronize in rare, “ideal” cases. Asynchronicity is the key to achieving polyphonic playing techniques on the cello, between the left hand—which defines the intervallic/ harmonic substance (theoretically, at least)—and the right hand, which produces the sounds(conventionally, at least). This asynchronicity is of a gradual nature—and can for this very reason be molded in different steps as a formal process with a range of different qualities. If the bow is introduced somewhat prematurely, for example, the open string will sound first, the fingered pitch only after this; if the bowing-action is delayed, however, it makes sense for the finger-action to be percussive, thus rendering the pitch audible. Such deviations are rhythmically still related to the “motive” in the left hand; if, however, the right-hand action is rhythmically autonomous (perhaps even in the string- changes), the degree of asynchronicity is substantially greater. This can be intensified through the insertion of “lacunae,” i.e., sudden interruptions of the bow-movement effected by leaving the bow on the string to stifle any resonance (stopping-action). Internal polyphony in the right hand constitutes a middle position In itself. Changes of bow-position and bowing-speed (and thus sound- presence) can —in combination with the dynamics, for example —underline the phrase-structure of the morphemes (perhaps by coupling diminuendo with più flautando or sharp accents with firm bow-pressure). The parameters can also, on the other hand, be treated completely independently. This can even be taken as far as playing directly on or behind the bridge, which no longer has any bearing on the pitch-production; alternatively, during a stopping action of the bow, a rapid oscillation between bowing with the wood and with the hair, or perhaps a longitudinal wiping-movement over the fingerboard. If the right hand becomes increasingly independent—i.e., not synchronized with the left—then the left hand must assert itself once again with the sparse means it has: finger-percussion, finger-percussion tremolo, left-hand pizzicato, exaggerated vibrato.

The cello, with its relatively strong body of resonance and its large range, is of all the string instruments that best suited to a deconstructive treatment of pitch-determined morphological structures by means of its manifold playing- techniques. The absence of morphemes (in cases of asynchronicity) can be indicated through the use of finger-percussion, and the cello can effectively carry out certain more absurd, ultimately more visually than sonically interesting actions (such as playing behind the left hand). The cellist, seated behind his instrument, is more mobile, and therefore more can be demanded of him—and these demands can extend to the presentation of an “unplayable” piece, the tragedy of a courier, if not between Faggio and Squamuglia, then at least between the music and its listeners.

The work’s strategy is one of self-destruction—it gives the solo piece an “identity,” and defines its function within the larger context of the poly-work Hommage à Thomas Pynchon. One could describe the process undergone by the piece as one of the increasing impossibility of playing the cello. The “Prologue” presents the virtuoso performer, who, the master of his expressive capabilities, plays in a manner which, though admittedly rather complex, is ultimately conventional in its integral synchronization of the left and right hands. The occasional intrusion of finger-percussion forms an exception to this rule, though it could—at this particular point—be viewed as an extension of the work’s vocabulary. “Act I” immediately surprises through its scrunch-tones and bow-stops, which rather undermine a “cultivated” mode of sound-production. In addition, asynchronicities between the parameters in the right and left hands become increasingly prominent (such as articulation entirely independent of the bow-notation, or autonomous longitudinal wiping-actions of the bow [as at the end of m. 16]) which disturb the piece’s sound world, though without giving rise to impairments of a more systematic kind. In “Act II,” in which the cello now bears the strain of the severe de-tuning of one of its strings, this asynchronicity is itself thematicized: for long stretches, the motivic structure in the left hand and the bowing-rhythms are treated independently—both syntactically and rhythmically speaking—, and the right-hand part itself consists of different temporal layers. The cello playing thus approaches what Cox himself terms a “virtual corporality,” which can only subsist through the (ultimately irrational) overlaying of contradictory, rationalized patterns of musical reproduction. “Act II” can thus be viewed as establishing and stabilizing a new mode of cello playing. Following the second de-tuning at the close of “Act II,” it does become clear, admittedly, that a re-definition of this sort is not the aim of The Courier’s Tragedy.

In “Act III,” now with a deeper, but feebler sound world, the cellist frantically attempts to assert his sovereignty through consciously demonstrative finger-percussion. If the right hand is already leading a life of its own, now even pausing or attending to itself not infrequently, rather as if the left hand did not exist (e.g., in the case of wiping-movements going beyond the bridge), then the left hand must at least demonstrate the pitch-production as such. In the first part of “Act IV” there are only sporadic bow-strokes (and even then—as in m. 52, which features a 23:18 tuplet for the string-selection, an 11:9 tuplet for the articulation and a polyphonic texture within the left hand—with a super- imposition of different structures of movement); aside from this, one finds predominantly finger-percussion, usually with tremolo, with pizzicati embedded within these. Following the general pause that leads into the second part —in the course of which a mute is affixed—a further restriction is applied to the expressive capacity of the instrument. But not only this: the player is instructed to play with the bow—initially col legno, this producing more audible results — behind the fingers, i.e., between the tuning-pegs and the left hand. Not only is it now no longer possible to produce the fingered pitches (which are still forced to assert themselves through finger-percussion), but this sequence at last leads to a crystallization of the particular theatrical quality—the work’s own visibility, its visual component—which had always been present in this spectacle of a performer exhausting all his resources and inhibitions (and indeed being constrained to do so) in this manner. As if through a need to set up an opposition to this “degenerate” manner of playing, the one remaining form of alternative sound-production, the pizzicato, takes on the dominant role (fortunately the text, with its abundance of proper names at this juncture, permitted this). This pizzicato, which alternates with the col legno playing behind the left hand, is further focused through an insert which I decided on after the form of the piece had already been conceived with a duration of 18 minutes in mind: m. 89 presents—as a depiction of the fifty murdered members of the Lost Guard of Faggio—50 absolutely identical Bartók-pizzicato on the low D for an entire minute, without the slightest mediation between itself and the events preceding and succeeding it. It is almost as if the music, which constantly operates within the realm of the absurd, and only temporarily—and then only reluctantly—takes on musical meaning in the sense of an “expressive” mode of cello playing, is seeking to regain its meaning through an “unambiguous” gesture which, as it constitutes a departure from the rest of the piece, can be assigned particular emphasis. Unfortunately, however, this gesture is and remains an extremely moronic one, and is unable—precisely for this reason—to assume any meaning whatsoever.

In “Act V,” which is substantially shorter than its predecessor, all that remains is for the cellist to bow behind the left hand, in fact directly by the tuning-pegs—and arco, which, despite the most forceful of action—“dynamics,” can only produce the most sonically impoverished of results, beyond any possible assignment to criteria such as pitch, motifs or rhythmic patterns; cello playing here displays its most ridiculous side. As if to compensate for this, a form of sound-production is introduced which had not previously occurred: the left-hand pizzicato, which is now integrated into the finger-percussion. But this too is lost in the mere statistics of a by now utterly meaningless procedure. With a violent, desperate gesture at the end of m. 116 (finger-percussion and normal pizzicato) the piece appears to break off. But an epilogue is still required, one which depicts a state of utter petrification: for over a minute, the cello performs vibrato on a silent quadruple-stop, as if obliged to elucidate its expressive meaning, while quiet col legno battuto actions on the strings behind the left hand and at a selection of neighboring points on the body of former resonance remind us that this instrument did, in fact, once serve the purpose of performing cello music.

Source: Musical Morphology. Hofheim: Wolke Verlag, 2004.

Return to: Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf Page

Main Pynchon Page: Spermatikos Logos

Contact:quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com