Pynchon Music: Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf

this will end when the last listener leaves the building

Out in a bloody rain to feed our fields

Amid the Maenad roar of nitre’s song

And sulfur’s cantus firmus.

—Richard Wharfinger, “The Courier’s Tragedy”

Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf (b. 1962)

Born in Mannheim in 1962, Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf studied composition with Brian Ferneyhough and philosophy with Jürgen Habermas. He wrote his dissertation on Arnold Schönberg, and in 1995 co-founded the Gesellschaft für Musik und Ästhetik (Society for Music and Aesthetics) at Freiburg. He has published several books, edits musical journals, and consults for various opera houses.

Pynchon Connection

Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf has described Thomas Pynchon as “one of the most important novelists of our time.” Pynchon’s second novel, The Crying of Lot 49, inspired Mahnkopf to write four individual pieces and a variation. It began in 2001 with The Tristero System, a musical homage to Pynchon’s underground postal network. This was followed by The Courier’s Tragedy, a twenty-minute cello piece derived from the novel’s “ill, ill Jacobean revenge play,” an insane piece of seventeenth-century Grand Guignol written by one “Richard Wharfinger.” Next was W.A.S.T.E., for solo oboe and live electronics, followed by D.E.A.T.H, an electronic meditation composed of work from the previous pieces. There was also W.A.S.T.E. 2, a simplified version of W.A.S.T.E.

In 2005 Mahnkopf combined these pieces into a theatrical work entitled Hommage à Thomas Pynchon. Designed in part to “defeat” and “exhaust” its performers, the work is also intended to disorient the audience by confusing the compartmentalized roles of a theater’s internal spaces. Upon leaving their seats, the audience finds the theater’s lobby has been wired for sound, with electronics continuing the performance ad infinitum. Indeed, Mahnkopf has suggested that the only way to conclude the performance is to become locked outside the building!

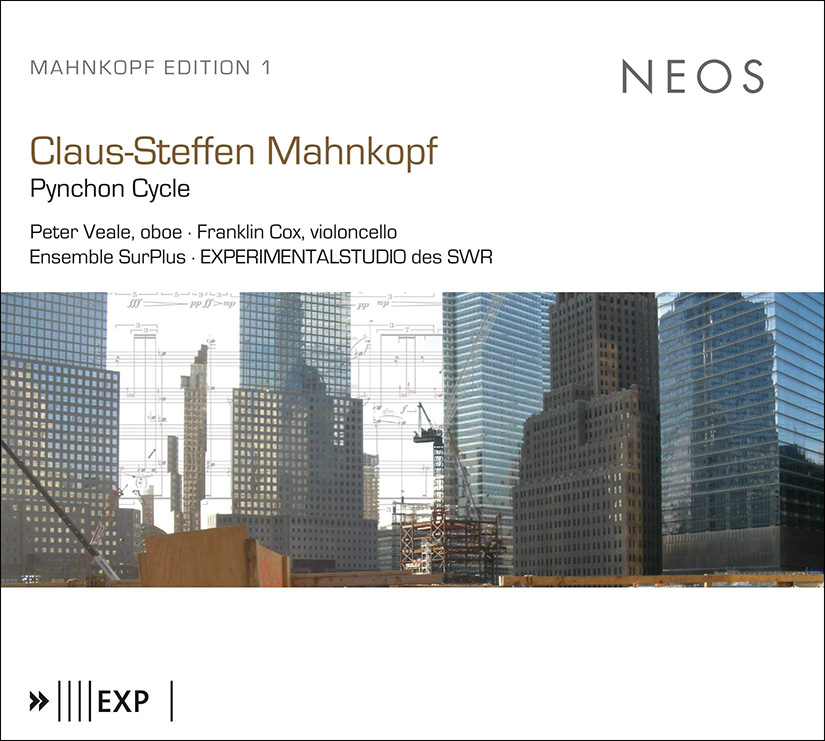

Although Hommage à Thomas Pynchon is designed to be experienced live, Mahnkopf has recorded the four principal Lot 49 pieces under the title Pynchon-Zyklus, or Pynchon Cycle. Lasting nearly 70 minutes, the Pynchon Cycle is the first CD in Neos’ “Mahnkopf Edition” series, and represents the most accessible way to enjoy—if that’s the right word?—the composer’s tribute to his fellow “paranoid.”

Review of Pynchon Cycle

First things first: Pynchon Cycle is not for the faint-hearted. Mahnkopf belongs to the spiky, dissonant, relentlessly atonal school of modern music—think of Harrison Birtwistle, or early Peter Maxwell Davies. The kind of music that earns furious applause from guys wearing Frank Zappa T-shirts underneath their black turtlenecks; but drives season-ticket holders to the exits muttering in disgust. Mahnkopf’s stated intention with Pynchon Cycle is to create something “hard, almost brutal, with the logical consequentiality of ultimately senseless procedures which appear to mediate everything with everything else,” using music “consciously acknowledged as hideous,” and expressing a sense of “paranoid meaninglessness.”

Part 1. The Tristero System

The Cycle kicks off with The Tristero System, scored for two pianos, two bass clarinets, three trombones, four piccolos, and two percussionists. Seventeen minutes of “sufficiently repellent post-urban sonic material,” the piece pits the instruments against each other in a cacophony of dissonant voices. We begin with a piano, its lower keys stroked and pounded in frustration, a furious and futile mining for a rhythmic figure that never quite appears. Shrill woodwinds are bullied aside by guttural brass, blaring and squonking like a band of fascist geese. The addition of frenzied percussion brings everything to a boiling point. A sustained, undulating drone on the brass attempts to impose order, but the orchestra resists, erupting into whirling pockets of resistance. The dialogue between the trombones and piccolos intensifies; but we’ve yet to hear from the star of the piece: the timpani. Some nine minutes into The Tristero System, the drums begin a furious, idiot pounding. This isn’t Beethoven’s “fate” knocking on the door, this is the 3:00 a.m. secret police, and they’re not happy.

This knocking is the only real anchor in the piece—it can hardly be called a “theme”—and it appears a few more times; here reduced to a restrained rapping, there threatening to hammer the door to splinters. In between these aggressive punctuations, the instruments continues to bicker, and Mahnkopf’s orchestrations remain remarkably colorful throughout—there’s some wondrously strange effects some thirteen minutes in that defy description, and it sounds like a kitchen’s being demolished somewhere near the 16:30 mark. There’s no real conclusion to The Tristero System: the piece ends when it ends; perhaps evoking the feeling of being locked outside the building? Or like a passing storm, the whirling tempest has merely traveled somewhere else?

Part 2. The Courier’s Tragedy

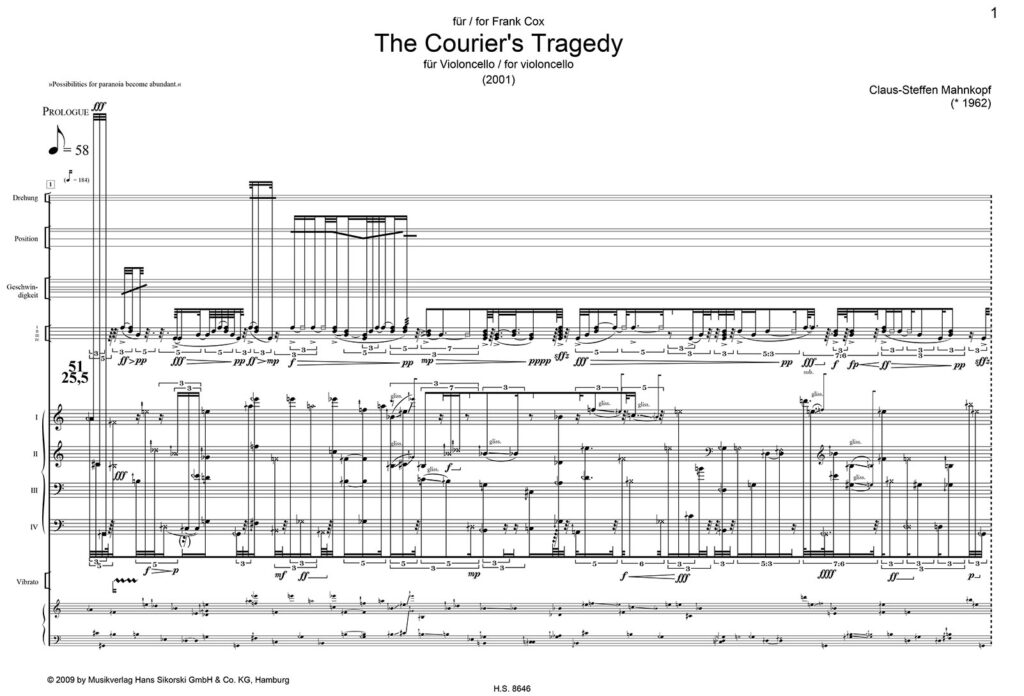

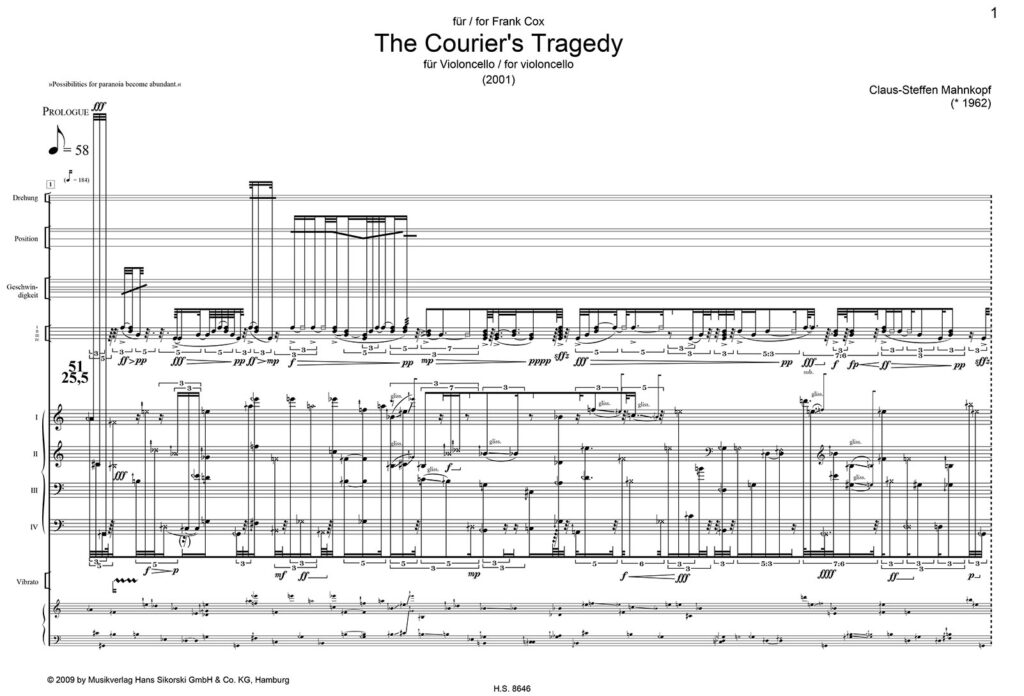

After a few seconds of welcome silence we’re onto The Courier’s Tragedy, scored for solo cello. Or it’s more accurate to say it’s scored twelve times for solo cello: the player is offered a dozen different notation systems, some of which are mutually exclusive. He’s expected to navigate this compositional labyrinth to some form of exit, usually by surrendering to despair. The piece is named after the fictional “Jacobean revenge play” described at length in The Crying of Lot 49, and is designed to follow its five-act structure and numerous violent incidents. Mahnkopf subjected this “play-within-a-play” to an algorithm that converted Pynchon’s text into “numbers and proportions,” and the score was based on this transformed cipher. Sort of pseudo-random aleatory music; and that’s not a bad description: The Courier’s Tragedy is twenty minutes of buzzsaw notes, scraping noises, and manic pizzicato. Despite being organized around a coded structure—which Mahnkopf himself calls “senseless,” and likens to “inhuman machinery”—the piece sounds like unbridled chaos, like a giant space mantis found a cello and said, “I can mate with this!”

The only segment that makes any “sense” occurs fourteen minutes in, when the cellist begins plucking the strings aggressively and repeatedly. This return of Tristero’s hammering lasts a full sixty seconds, but now suggests slashing rather than knocking—the “refreshingly simple mass stabbing” of Pynchon’s Ercole by way of Bernard Herrmann? (According to Mahnkopf, this section of “simple stupidity” is “the Lost Guard of Faggio, the corpses of whose 50 members are found in a lake.”) After this moment of “order” crumbles, we’re back to the sound of a cello being systematically deconstructed. The cellist’s fumbling becomes increasingly audible, until all that remains is an exhausted tapping on the wooden body of the cello, “the shortest line ever written in blank verse: T-t-t-t-…”

“Possibilities for paranoia become abundant.”

Part 3. W.A.S.T.E.

An oboe comes screaming across the sky, and we begin Part 3, W.A.S.T.E. The harshest piece in the Cycle, W.A.S.T.E. uses live electronics to amplify and distort a solo oboe. While W.A.S.T.E. features all the sounds you expect from European avant-garde electronics—hissing bursts of static, blurting bubbles, spacey drones—it’s the oboe that quickly induces a migraine. Pushed to its highest register, the shrill woodwind becomes a creature that just won’t die, its tortured shrieking mocked by the chilly electronics. The end comes eighteen minutes and thirteen seconds into the piece, which is eighteen minutes and twelve seconds too late. Of course, Mahnkopf intends W.A.S.T.E. to sound “brutal,” “ugly,” and “insufferable,” but this borders on the comically unlistenable—a classical version of Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music.

Part 4. D.E.A.T.H.

Although described as the third part of the Cycle in Mahnkopf’s liner notes, D.E.A.T.H. is the fourth and final track on the Neos CD. A twelve-minute electronic drone, D.E.A.T.H. shares many similarities with the work of Stockhausen, the electronics composer mentioned by name in Lot 49. Unlike its predecessor W.A.S.T.E., D.E.A.T.H. doesn’t overstay its welcome; but contains a metallic bitterness that prevents it from being mistaken as ambient music. Its spacey texture is occasionally wrinkled by small moments of acoustic intrigue—a lisping snippet of backmasking, a glassy chorus of electrons, the brush of something large stumbling in the dark. According to Mahnkopf, the electronic manipulations of D.E.A.T.H. represent the “final decomposed state” of material used earlier in the Pynchon Cycle. Serving as a kind of acoustic heat death to the Cycle, the piece calls to mind another of Pynchon’s favorite themes—entropy.

While the music of the Pynchon Cycle is unapologetically abrasive, the CD is impeccably performed, recorded, and produced. This is especially evident in The Tristero System, which has the most challenging dynamics and orchestrations of the Cycle. Every instrument is distinct and well-spatialized, which makes the piece surprisingly intelligible for being so cluttered. The liner notes are satisfyingly detailed, and are available as a PDF with the Presto Music digital download.

Mahnkopf’s Notes

All of the information in this section has been compiled from Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf’s web page, and was written by the composer. It’s presented here to bring a more coherent sense of order to the Pynchon Cycle. The actual liner notes to the Neos CD follow.

The Pynchon Cycle

The starting point of the Pynchon Cycle is the novel The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon, who I consider one of the most important novelists of our time, and with whom I feel much in common, above all a paranoid world-view of a thoroughly amoralized and dehumanized (entbürgerlicht?) society, as can be seen in the present-day megapolis. In a conscious distancing from other cycles of the immediate present—such as those by György Kurtág, Daniel Libeskind and Zaha Hadid—I was concerned in this cycle with something hard, almost brutal, with the logical consequentiality of ultimately senseless procedures which appear to mediate everything with everything else, without being able to create thereby anything meaningful. To this “hardness” I responded in my selection of material, consciously acknowledged as hideous; in addition, the compositional and therefore formal strategies are settled on the border of what a composer educated in the fine old European tradition might consider fractured and distorted. Each work in the Pynchon Cycle translates the narrative structure of the aforementioned novel (or an excerpt from it) into a mechanical sequence of numbers and proportions that is applied to as many levels of the construction as possible. In this fashion, the cold rationality of complex interconnections comes together with a paranoid meaninglessness.

The Tristero System (2001)

For ensemble [18′]

4 picc.0.2 bass cl.0 – 0.0.3.0 – 2 perc (bass dr, cym, 2 Tibetian cym, large tam-t,

flat Chinese tam-t, bottles, bronze foil, 5 variable metal objects). 2 pianos

First performance: 28 October 2007, Leuven. Ensemble SurPlus – James Avery (conductor)

The Courier’s Tragedy (2001)

For violoncello [19’]

Commissioned by the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Sience, Research and Arts

First performance: 1 March 2003, Baltimore. Frank Cox

The Courier’s Tragedy translates the narrative structure Renaissance horror-play of the same name from The Crying of Lot 49 by means of a mechanical sequence of numbers and proportions, which are applied to all levels of the construction, this consciously independent of whether this was musically “sensible” or not. The cold rationality of a complex networking here corresponds to a paranoid sense-lessness. In The Courier’s Tragedy, the cellist is placed in an absurd situation: the score is notated on 12 systems, which simultaneously offer a multitude of potentials for sonic shaping and, due to their internal contradictions, appear to render their realization impossible. During the course of the theatrical piece unfolded in a prologue, five acts and an epilogue, the sovereignty of the interpreter as master of the instrument is systematically undermined, until at the end the possibility of playing the cello itself is rendered impossible. Exhausted and robbed of his expressive capabilities, the player plays in a void and attempts in vain to attain melodic quality from the wooden body, a quality that the four strings have long since surrendered.

Mahnkopf’s more extensive notes on

The Courier’s Tragedy can be read

here.

W.A.S.T.E. (2001/02)

For oboe and live electronics [12′]

First performance: 12 August 2004, Darmstadt. Peter Veale (oboe) – Experimental Studio of the Heinrich Strobel Foundation of SWR – Joachim Haas and Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf (sound direction)

Several years of work at the SWR Experimental Studio resulted in works from the Pynchon Cycle that also revolve around the oboe: D.E.A.T.H. and W.A.S.T.E. ‘W.A.S.T.E.’ is an acronym from The Crying of Lot 49, where it stands for the words ‘We Await Silent Tristero’s Empire’.

D.E.A.T.H. (2001/02)

For eight-track tape [12′]

First performance: 12 June 2004, Bourges

All sound materials of D.E.A.T.H. are electronically treated oboe-multiphonics. I am deeply indebted to André Richard who allowed me to work at the Experimentalstudio in Freiburg.

W.A.S.T.E. 2 (2002)

For oboe and eight-track tape [18′]

First performance: 19 February 2003, Stanford. Peter Veale (oboe)

W.A.S.T.E. 2 is a simplified version of W.A.S.T.E. for oboe and playback.

Hommage à Thomas Pynchon (2003-05)

Music installation for ensemble, violoncello and live electronics [Duration: unlimited]

Commissioned by MärzMusik

4 picc.0.2 bass cl.0 – 0.0.3.0 – 2 perc (bass dr, cym, 2 Tibetian cym, large tam-t,

flat Chinese tam-t, bottles, bronze foil, 5 variable metal objects). 2 pianos

First performance: 6 March 2005, Berlin. Frank Cox (violoncello) – Ensemble SurPlus – James Avery (conductor) – Experimental Studio of the SWR Heinrich Strobel Foundation – Joachim Haas (music informatics and sound direction) – Michael Acker, André Richard and Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf (sound direction)

This piece is ensemble music, music theater as well as a music-installation. I would like to illustrate my concept by explaining the performance order and structure of the Hommage à Thomas Pynchon. At the beginning the live ensemble piece The Tristero System is played as if this were a conventional concert situation. During this piece the electronics begin to interact with the ensemble (recording, sound-processing etc.) and to develop independently so that by the end the ensemble piece comes to no conclusion. The electronics continue, creating the impression that the piece continues although the players have ceased to play and have left the stage. The electronics continue using various materials: —the prerecorded ensemble material—parts from the tape for W.A.S.T.E.—the recorded cello solo—the entire ensemble piece. The electronics consist of a large number of computer-controlled sound-machines. A kind of electronic écriture automatique continues the piece in a complex and kaleidoscopic way. After a while—the players have left the stage—the cello soloist appears and tries, by playing the piece The Courier’s Tragedy (prologue, five acts and epilogue), to control the electronics, even to destroy them. He fails: he is able to manipulate the sound-design, but in the last instance he himself will be destroyed by the electronics. After reaching a state of exhaustion, the player leaves the stage. The electronic music has reached the maximum of insufferability. During the second hour the effects of the cello piece will entirely disappear. Therefore what remains is nothing more than a (very violent) music-installation, theoretically having no end (more pragmatically, this installation will end when the last listener leaves the building). During this second hour the listeners will leave the concert hall believing that the event is over. In the foyer they perceive that the entire house (the theater) is filled with music coming from numerous loudspeakers, similar to that in the concert hall but with deconstructive effects of territorialization and deterritorialization. They are therefore urged to explore the total area or to leave it when they want. It is necessary that the listener/visitor has no way to reenter the building through the normal entrances and exits. When, after having decided to leave the event, he enters the last anteroom and hears the tape piece D.E.A.T.H. (also being repeated endlessly) which will be an unexpected surprise. Here, too, he will have to decide how long he wants to remain. For those who intend to come back, it will be possible to use a back door—the parcours can then begin again.

Der Pynchon-Zyklus (CD Liner Notes)

The following are the Neos CD liner notes for Pynchon Cycle, written by Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf:

In the summer of 1998 I felt a double need: firstly, I wanted to work on two entirely contrasting work cycles in order to expand the range of my music and to be able to probe its extremes. One of these cycles would be dedicated to the composer György Kurtág. Secondly, I wanted to dedicate a homage to one of my favorite writers, Thomas Pynchon. I realized immediately that if I was to respond with an Hommage à Thomas Pynchon, it would have to be every bit as exceptional and eccentric as Pynchon’s work and particular circumstances, such as the fact that we have no knowledge about the author, most obviously not even his appearance. I thus had to thoroughly modify my manner of composition—in its material, its techniques, its sound world and its ultimate performative character in concert—at least for this purpose. It would have been too simple merely to invent a music whose character suited Pynchon’s semantics, a semantics that posits significatory relations on all sides while simultaneously contravening them. My approach would have to be fundamental. It first of all required a sound world capable of giving expression to the destructivity of today’s society, especially that of the mega-metropolises. This was only possible with musical electronics, so I turned to the EXPERIMENTALSTUDIO des SWR (Freiburg) in order to learn the necessary skills. Then I required a hypertrophic form. I decided on a poly-work consisting of several works that served different functions within the overall form. The Pynchon Cycle consists, in addition to the composite piece Hommage à Thomas Pynchon (2003–2005), of the following:

1. The ensemble piece The Tristero System, whose instrumentation of two pianos, two percussionists, two bass clarinets, three trombones and four piccolos offers sufficiently repellent post-urban sonic material;

2. The solo cello piece The Courier’s Tragedy, which literally depicts, musically and above all performatively, the tragedy of the soloist who fails in the attempt to control, in fact to defeat an inhuman machinery;

3. The harmonically ugly tape piece D.E.A.T.H. (8-track), which literally presents the final decomposed state of the material resources employed (D.E.A.T.H. is an acronym by Pynchon: “Don’t ever antagonize the horn”);

4. Finally the piece W.A.S.T.E. for oboe and live electronics, which is not actually heard during Hommage à Thomas Pynchon, yet whose sound material slumbers in the computer’s memory as an unconscious layer, occasionally taking effect in a shifted state (W.A.S.T.E. has a partner piece—W.A.S.T.E. 2—for oboe and 8-track tape) (W.A.S.T.E. is an acronym by Pynchon: “We await silent Tristero’s empire”).

The form of this poly-work had to be conceived as a shattered one from the outset. I decided to take this to its extreme and make the work infinitely long—a music without any temporal end, one that made the greatest possible demands on the art industry, a permanent threat: an untreatable paranoia, as it were. Strictly speaking, the spatial dimension would also have to be extended into the infinite. It should sound not only in a single performance location, but virtually the whole city, the whole region, the whole world. For pragmatic reasons, which can unfortunately not correspond to artistic ones, the duration is limited, and the space even more so. One will inevitably have to organize a “concert,” an event with a fixed time and a predefined location.

The four works listed above can be performed independently. Hommage à Thomas Pynchon incorporates the first three works. The work is simultaneously ensemble music, musical theater and a music installation, and this combination is therefore innovative in so far as it makes use of the newest technology to do something that would previously have been impossible, simply because these resources had not been sufficiently developed: the initiation of a real-time computer-assisted compositional process that sounds like composed, not algorithmic music, which latter composers in that field were previously forced to content themselves with. I was not concerned with presenting the latest craze in live electronics, quite the opposite: it was only through the fact that that live electronics now possessed a sufficient capacity for complexity and differentiation—and that also means: the possibility of polyphony—that I was able to become creative in this genre.

I did not simply take narrative threads from Pynchon’s body of work—in this case I was using the novel The Crying of Lot 49—and translate them into music. The dramaturgy of the cello piece in particular is identical to that of the systematic murder of all the protagonists in that novel’s “Jacobean Revenge Play” between Faggio and Squamuglia. I attempted to incorporate as many connections as possible at an abstract, and therefore musically absurd level: I scanned the entire text of the novel and converted it into hundreds of thousands of numbers, which, turned into algorithms, determined the sonic and musical flow of Hommage à Thomas Pynchon with its parallel identities. Admittedly, I had to push the absurdity of this abstract material application to such an extreme that it would take shape and—paradoxically—could almost become as meaningful as Pynchon’s novels, which, read in the right manner—i.e. repeatedly—enable us to read and thus experience the world, this so damned dichotomous world of ours, like some great Borges-esque library.

Hommage à Thomas Pynchon is of an extremely performative character. At the start, the 18-minute ensemble piece The Tristero System is played in the main performance space (the “concert hall”) as if one were attending a normal concert. At the same time, the Pynchon architecture with its computer program is started. It creates an “automatic writing” based on the material sounding on stage. The sound technician fades in—in an improvisatory fashion—this electronically-altered music via the hall’s loudspeaker system. As the instruments of the ensemble form its initial sound material, the two layers mingle well, avoiding any interruption once The Tristero System is finished and the musicians leave the stage unapplauded. Now the central concern is the deliberate simulation of a continuation of this ensemble music with other means.

After a while, the cello soloist appears and attempts to counteract and ultimately defeat the electronics with his piece The Courier’s Tragedy (in five acts with a prelude and a postlude). He fails, and must fail, because the cello piece follows precisely the same dramaturgy. He may be able to manipulate the sonic events, but is ultimately “killed” by them. He too leaves the stage, exhausted. After an hour the situation changes: the hall doors are opened, and from a distance the 28 loudspeakers in the four acoustic spaces announce to the audience that the music is also playing elsewhere. At the same time the continuation of The Tristero System, i.e., the sound-processed material of the “automatic writing,” is turned off (it is now heard in all four acoustic spaces), and D.E.A.T.H. is played instead in the concert hall and looped indefinitely.

Because of the specific performative character of Hommage à Thomas Pynchon, which is heard in five (or several) separate acoustic spaces, a CD documentation is not possible.

The performance of my works makes great demands on the performers. I would therefore like to extend my special thanks to the soloists Peter Veale and Franklin Cox, for whom the solo pieces were written; the EXPERIMENTALSTUDIO des SWR, where I was able to work over the course of several years, its then director André Richard and the music computing specialist Joachim Haas; and finally Ensemble SurPlus, together with its director James Avery, for decades of support.

Further reading: Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf, Marginalien zu Thomas Pynchon, in Mahnkopf, Die Humanität der Musik. Essays aus dem 21. Jahrhundert (Hofheim: Wolke, 2007); The Courier’s Tragedy. Strategies for a Deconstructive Morphology, in Mahnkopf et al. (eds.), Musical Morphology (= New Music and Aesthetics in the 21st Century, vol. 2) (Hofheim: Wolke, 2004); Hommage à Thomas Pynchon, in Mahnkopf et al. (eds.), Electronics in New Music (= New Music and Aesthetics in the 21st Century, vol. 4) (Hofheim: Wolke, 2006).

—Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf, 2010

Translation: Wieland Hoban

Albums

Track Listing

1. The Tristero System (18:04)

2. The Courier’s Tragedy (19:03)

3. W.A.S.T.E. (18:04)

4. D.E.A.T.H. (11:48)

Musicians

Ensemble Surplus; James Avery, conductor (1).

Franklin Cox—cello (2).

Peter Veale—oboe (3).

ExperimentalStudio des SWR—electronics (3, 4).

Track Listing

1. Gorgoneion (17:43)

2. Illuminations du brouillard (1) (3:01)

3. Solitude-Nocturne (15:24)

4. Illuminations du brouillard (2) (2:55)

5. W.A.S.T.E. 2 (18:12)

6. Illuminations du brouillard (3) (3:06)

7. Hommage au hautbois (16:24)

Musician (Track 5)

Peter Veale—oboe.

Additional Information

Pynchon on Record

Return to the main music page