Jules Siegel’s “Who Is Thomas Pynchon… And Why Did He Take Off With My Wife?”

Who Is Thomas Pynchon… And Why Did He Take Off With My Wife?

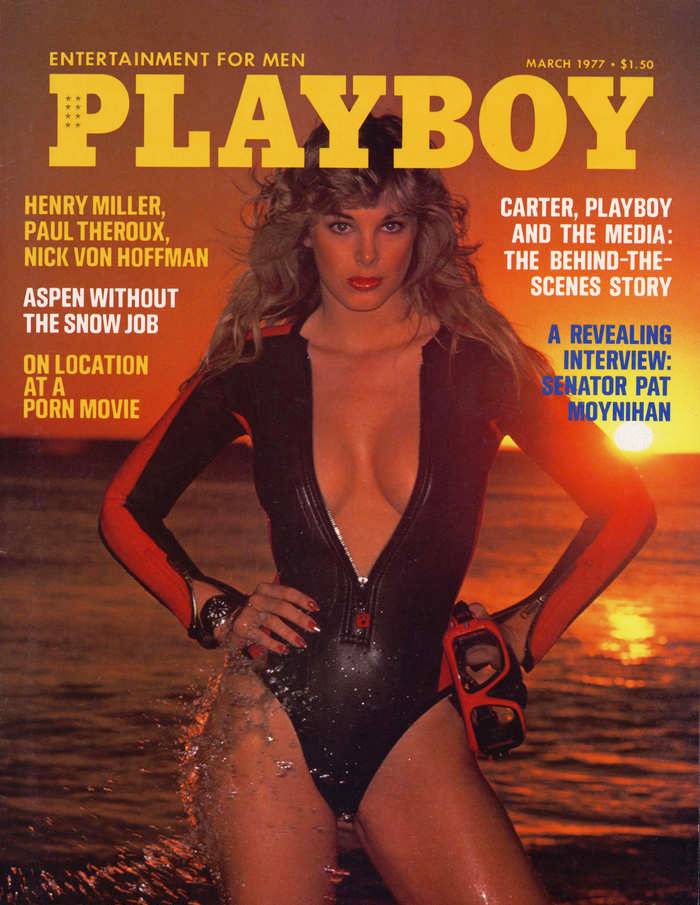

Playboy

March 1977

By Jules Siegel

Weisman speculated that this was “evidently intended to make fun of the fact that the Pynchon novel, while hailed as a work of genius, also left many of its readers confused and baffled by its encyclopedic references and intricate, fantastic style.” Confused though the literary world may be by the mysterious Pynchon and his labyrinthine allegories, he has received unprecedented acclaim. V. won the William Faulkner Prize. His second novel, The Crying of Lot 49, took the Rosenthal Award in 1967. Gravity’s Rainbow was the unanimous nomination of the Pulitzer fiction jury in 1974, but the advisory board of eminent journalists disagreed, calling the book “obscene,” “unreadable” and “overwritten.” The trustees skipped the prize entirely that year.

In 1975, Pynchon declined the William Dean Howells Medal of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, given every five years for a distinguished work of fiction, breaking silence with a brief note saying he know he ought to accept the gold medal as a hedge against inflation, but no, thanks, anyway. The academy said it would hold it for him in case he changed his mind. Although he has never had a best seller, Pynchon’s books have been commercially successful. there are more than half a million copies of V. in print. Somewhere back of that pile of paper and ink there is a question mark named Thomas Pynchon, location unknown, of no fixed address, his biography a mere few sentences, physical description unavailable. Who is Thomas Pynchon, really? Why is he hiding? Does he exist at all, or is he no more than an elaborate hoax of the Age of Paranoia, like the hallucinatory inventions of Argentina’s blind fabulist, Jorge Luis Borges? Who is Thomas Pynchon and what does he mean?

•

Everyone has his own fantasy of success. I once had no greater hope than to publish a learned paper on 17th Century English songs in The Proceedings of the Modern Language Association. Somewhere in the blank fog of time there is a scholar writing a learned paper on Thomas Pynchon. To him I offer this footnote: In Mortality and Mercy in Vienna, Pynchon’s first published short story, the protagonist is one Cleanth Siegel. My second wife, the former Virginia Christine Jolly of San Marino, California, tells me that the character represents me. I have noticed the coincidence of name but do not recognize myself. Possibly it is a me I have never been able to examine very well, the back of my neck, or the dream of Gabriel García Márquez, whose essential quality is that it cannot be remembered.

Be that as it may, I did attend Cornell in 1954. The boy in the next room was Thomas Ruggles Pynchon, Jr. If there are any correspondences to be found in that or anything else that follows, I leave them to Chrissie and the scholars.

Tom Pynchon was quiet and neat and did his homework faithfully. He went to Mass and confessed, though to what would be a mystery. He got $25 a weeks pending money and managed it perfectly, did not cut class and always got grades in the high 90’s. He was disappointed not to have been pledged to a fraternity, but he lacked the crude sociability required for that. Besides, he had his own room at Cascadilla, one of the more pleasant dormitories, not tight College Tudor tile but pre-Civil War Victorian, high-ceilinged and muted. Fraternity houses offered neither the charm nor the privacy, and he was, if anything, a very private person.

Pynchon was then already writing short stories and poems, but he did not hand them about very much. I remember one story that had something to do with a broken pitcher of beer. I once saw some French quatrains in what looked like his hand—small, regular, precise engineer’s manuscript. He later denied ever having done anything like that. Maybe they were a girl’s, but I never met her, as far as I know.

I have seen photographs of William Faulkner that made me think of Tom. He was very tall—at least 6’2”— and thin but not skinny, with a pale face, fair eyes and a long, chiseled Anglo nose. He was ashamed of his teeth and did not smile much. Many years later, writing to me from Mexico City, where he was having extensive and painful dental restoration done, he described them as “misshapen choppers” and said they had determined his life in some unspecified way that seemed very important to him.

His wit was terrifically bold for such an otherwise cautious personality. He could carry a tune well and made up ribald parodies of popular songs, which I seem to remember—surely I am imagining this—were accompanied on a ukulele. From the musical notations in the back of T.S. Eliot’s The Cocktail Party, he puzzled out for me the tune of One-Eyed Reilly, which we sang together one beer-soaked night in joyous disharmony and stole an old wooden rocking chair off someone’s porch and tossed it into the interior court of Cascadilla Hall. It landed upright on the roof of a covered crosswalk and rocked itself quiet. Possibly it is still there.

When his parents came to visit, he introduced his mother this way: “Jules, this is my mother. She’s an anti-Semite. I just didn’t want my children to surround themselves with Jews.” I remember her as an exceptionally beautiful woman, all cut glass, ivory and sable. I believe she had been a nurse, had a lot of Irish in her and was a Catholic. Though Mr. Pynchon was a Protestant, she raised their children in her own faith. Tom was the oldest. Then came Judith, about five years younger. The youngest was John.

I had more contact over the years with Mr. Pynchon than with Tom’s mother, but he is less clear: curly, lightish hair, red nose, very friendly and tolerant. He was commissioner of roads for the town of Oyster Bay, Long Island, and Tom worked with the road crews in the summer. Mr. Pynchon later became supervisor of the town of Oyster Bay and is now an industrial surveyor. The Pynchons lived in a very plain New England frame house on Walnut in East Norwich, its most notable furnishings some excellent Colonial portraits of ancient Pynchons.

It is an old American family, dating back to William Pynchon, one of the founders and principal citizens of Springfield, Massachusetts, who left England March 29, 1630, with John Winthrop’s fleet, accompanied by his wife and three daughters. His son, John, seems to have come over later on a different ship. The Pynchons are prominent in New England historical literature. William and John were magistrates and military officers. Their court record has survived and has been published in a carefully annotated edition by Harvard University Press, with a frontispiece portrait of William Pynchon. There are Tom’s eyes and a lot of his nose and shape of face.

William Pynchon is remembered for his role in the witch trials, in which he appears to have been a relatively moderate force, and for his highly controversial book The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption, a protest against the rigid Calvinistic theology of his time, evidently the first by an American author. It was officially censured by the General Court, which ordered a rebuttal written, summoned Pynchon to explain himself and directed the book burned by the executioner in the Boston market place. Soon afterward, William Pynchon returned to England, leaving John to supervise the family’s substantial holdings in the New World. He died October 29, 1662, and was buried in the churchyard at Wraysbury.

Although John Pynchon was an important man in his own time, an increasing obscurity gathered about the name. The Pynchons were Tories during the Revolution but loyal citizens of the republic afterward. By the time Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote The House of Seven Gables, in which a Pynchon appears in a not very attractive characterization, it seems that the family was virtually unknown. To Hawthorne’s surprise, however, surviving Pynchons vigorously protested. In a letter dated May 3, 1851, Hawthorne apologized and wrote that he thought no great damage had been done, “but since it appears otherwise to you, no better course occurs to me than to put this letter at your disposal, to be used in such manner as a proper regard your family honor may be thought to demand.”

Of the fate of the Pynchon family fortune, not much is to be found. They were gentry in England and gentry here. In the first half of the present century, the Wall Street Firm of Pynchon & Co. went under with scant attention, except for the comment of a Morgan partner that “these ripe apples must fall.” When I knew them, the Pynchons appeared to be in relatively modest circumstances hardly in want.

Though there are some well-known and evidently quite prosperous Pynchons—notably, the original Thomas Ruggles Pynchon—to be found in the standard biographical dictionaries and encyclopedias, the two most illustrious are separated by more than 300 years, covering the entire history of the nation. Indeed, it is not pure hyperbole to suggest that, in some measure, William Pynchon of Springfield and Thomas Pynchon of modern literary fame define the spectrum of our intellectual history. The records of the Pynchon family are easily accessible to any competent researcher. Curiously enough, no commentator on the younger Pynchon’s work seems to have made the connection with his ancestor.

•

How close were Tom and I at Cornell? It is hard to say, really. We were friends, maybe at some points best friends, very much alike in some important ways. We were both writers, both science students—he in electrical engineering, I in premed—both quite solitary and shy. Like him, I had no luck fraternity row. Unlike him, I was not diligent, was careless with money, attended class rarely, hardly got grades at all, much less high ones. One weekend between sessions, we hitchhiked from Ithaca to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where I wanted to see a girlfriend named Esther Schreier at the University of Michigan. If you think that name is dissonant, try Esther Chachkis, which is what she became when she married. It was blinding cold. We crossed Canada at night. Ann Arbor was sodden with stale snow. Esther had the flu and was not in a very romantic mood, though pleased to see me. Tom refused a date for himself and spent the evening at the observatory. On the way back, we got stranded on the bridge between Detroit and Ontario for about eight hours waiting for a ride, freezing outside between brief shelters in the relative warmth of the men’s room until the guards took pity on us and invited us into their hut and got us a ride.

This time, we blasted across the barren winter reaches with a wild pair of couples in a sedan and a pickup truck who played tag with the two vehicles in the darkness before dawn at speed upwards of 80 mph, sometimes turning their headlights off to ensure surprise. One of us—I forget which—left his bag in the car when they let us off in Buffalo. Tom remembered the first name of one of the men and that he worked for cab company. We had to wait a couple of hours or more in a White Tower Hamburger stand until the cab companies’ telephones were answered. Then we tracked them down and got the bag back. It took us most of the day to get back to Ithaca. Tom began talking with the Southern Colonel’s accent, not only to me but also to everyone we met. Before long, I was pleading with him to stop.

Not long after that, I dropped out of school and went into the Army, winding up in the Military Intelligence service in Korea, where I received a letter from Pynchon informing me that he, too, had left school and now was—I laughed out loud at the piquant turn of speech—“a jolly jack-tar.” He returned to Cornell, an English major this time, where Vera Nabokov thinks she remembers grading his papers for her husband’s class. Of Vladimir Nabokov, Pynchon told me only that his Russian accent was so thick he could hardly understand what he was saying. I did not return to Cornell but went, instead, to Hunter College.

I saw Pynchon occasionally in New York. Once he took me down to Greenwich Village to the Cafe Bohemia, where Max Roach was playing. It was the only band I ever heard in which the drums carried the melody. The Modern Jazz Quartet and the Kent Micronite Filter commercial were about as much modern music as I could handle. Pynchon, however, was deeply into the mysteries of Thelonious Monk. On religious grounds, I excused myself from attending chapel with him at the Five Spot to hear “God” play. I was an atheist.

Tom came down to the Bronx to my engagement party, helped do the massive load of dishes and stayed overnight with us. In June 1958, Mr. Pynchon arranged for the marriage ceremony to be performed by a Federal district court judge in Massapequa, Long Island, and I went out to East Norwich to take care of the final details. Judith was there, 16 and more than fair. I blushed with lust and wondered why I was getting married. When the appointed day came, we arrived at the judge’s mansion to find his worship in a tuxedo. It seemed that a few days earlier, another young couple named Siegel had come to him and asked to be married. Thinking it was us, he had done so and crossed our name off his appointment calendar. Fortunately—is that the right word?—Tom arrived early and intercepted the judge, who was getting ready to go off to a diner. The marriage proceeded as planned. Phyllis DeBus became Mrs. Jules Siegal. Pictures were taken. In one of them, there was Tom, bearded, wearing a charcoal-grey suit. Perhaps Phyllis still has that picture. We were divorced less than four years later, our marriage a victim of deep family tragedies. I think of her occasionally with great affection and a certain longing. She was so wonderful a lover, generous and easily aroused, but I was too callow then to appreciate her.

Tom visited us when we were living in Queens, once helping us move from one apartment to another, playing a wastepaper basket as a conga drum in the back of the rented step van. Another time, he came down from Ithaca with his girlfriend, Ellen Landgraben, a coed at Cornell. It was a forbidden love. She was Jewish and her parents objected to Tom. It was my job to drive her out to Hewlett and pretend that I had brought her from school. At the last minute, I forgot to remove my shiny wedding band. I don’t know if they noticed, though.

I remember another visit shortly after I was graduated from Hunter and was working for a public-relations agency. The firm was soliciting an account in the field of atomic research that manufactured plastic mannequins called radiation dummies, made of materials designed to absorb radiation in exactly the same way as the human body. One model had a human skeleton. The other was all plastic. Both had clear skins of something like Lucite and were eerily beautiful. I had the literature at home. Tom took some of it with him when he left. I was not to see him again for more than five years.

There were letters. Eventually, the total was something like 30. They began from Seattle, where he worked on the Boeing company magazine. I remember one from Florida. He was then living with a girl and they had gone to visit her family. A cute preteen attracted Tom’s notice enough for him to mention her lasciviously. Soon the letters had a Mexico City postmark. The Mexicans laughed at his mustache and called him Pancho Villa. In the rainy season, he awoke one morning to find a drowned rat on his balcony. Guanajuato was a town of stone corridors twisting back on one another. I had complained about the complexity of V. “Why should things be easy to understand?” he retorted and followed with a brief dissertation on the origins of the simple English movement in the studies of comprehensibility of newspaper copy commissioned by the Associated Press. The death of Marilyn Monroe grieved him heavily. The girl was no longer with him. This letter was written with a brand-new Mexican ribbon. He was gnashing his misshapen choppers in envy of my corrosively elegant first drafts of short stories and letters complaining of my inability to write. The return addresses changed, but the form of the letters was always the same: neatly typed on engineer’s quadrillé paper, the signature in faint pencil, “Tom.”

By 1965, he was living in Manhattan Beach. California. I had given up the public-relations business and was freelancing for magazines. The Saturday Evening Post sent me to California to do a story on Bob Dylan. I found Tom in a one-room apartment with a view of the sea. There were some shabby furnishings, a large gas heater, a narrow cot, a few books—one, Totempole, by Sanford Friedman—little else; a monk’s cell decorated by the Salvation Army. I told him about the Dylan assignment. “You ought to do one on The Beach Boys,” he said. I pretended to ignore that. A year or so later, I was in Los Angeles again, doing a story for the Post on The Beach Boys. He bad forgotten his earlier remark and was no longer especially interested in them. I took him to my apartment in Laurel Canyon, got him royally loaded and made him lie down on the floor with a speaker at each ear while I played Pet Sounds, their most interesting and least popular record. It was not then fashionable to take The Beach Boys seriously.

“Ohhhhh,” he sighed softly with stunned pleasure after the record was done. “Now I understand why you are writing a story about them.”

Another time, Chrissie was there. I had met her at a Beach Boys record session. She was then a few months older than 18, still wearing a thin wire brace on her big white teeth. Of Chrissie, it is necessary to post certain warnings. It is easy to underestimate her intelligence, but it is a mistake. She is obviously too pretty to be serious, conventional wisdom would have you believe. In New York, she was offered a screen test by Carlo Ponti the first week we arrived. She turned him down, likewise a modeling contract with the Ford agency, beginning with a recruiting commercial for the Coast Guard. The lady is full of surprises that do not go with a Pepsodent smile, shy and expert in the arts of invisibility, detesting stereotyped response. Her beauty is a device used to deflect inquiry, like the bullfighter’s cape. There is the kiss of the rose on the point of a sword. When Tom left, I took him down to his old green Corsair parked at the bottom of the hillside. “Don’t worry about her,” he said.

“What is that supposed to mean?” I asked.

“I think you worry about her. Don’t. She can take care of herself.”

We spent several days together, the three of us. One night we all went up to Brian Wilson’s Babylonian house in Bel-Air. Brian then had in his study an Arabian tent made of crimson and purple Persian brocade. It was like being inside the pillow of a shah. There was one light, fashioned from a parking meter. You had to put pennies in it to make it stay on. Brian brought in an oil lamp and tried to light it. The parking meter light kept going out and Brian kept dropping the oil lamp and stumbling over it. Neither he nor Pynchon said anything to each other. Another night, we went to Studio A at Columbia Records, only to find our way barred by one of Brian’s assistants, Michael Vosse, who explained that we couldn’t come in anymore, because Chrissie was a witch and fucking with Brian’s head so heavy by ESP that he couldn’t work.

One afternoon, Chrissie and I drove out to Manhattan Beach to see Tom, taking along with us some grass we had scored at a be-in (remember be-ins?) in Griffith Park. Tom was then living in a two-room studio with kitchen that had evidently been converted from a garage. It was on a side street a couple of blocks up from the beach. The decoration was pretty much the same. A built-in bookcase had rows of piggy banks on each shelf and there was a collection of books and magazines about pigs. The kitchen cabinets contained not groceries but many empty Hills Brothers coffee cans in orderly array, as if displayed on supermarket shelves.

His desk sat next to a window in the small living room. It had a clutter of miscellaneous papers, letters from obscure publications pleading for articles, an Olivetti portable typewriter, a thick stack of that graph paper covered with script—the draft of Gravity’s Rainbow, which he was in the process of typing and rewriting. He felt that he had rushed through The Crying of Lot 49 in order to get the money. He was taking no such chance with the new book, apparently having begun it soon after the publication of V., interrupting it to write The Crying of Lot 49. Much of the draft was done in Mexico. “I was so fucked up while I was writing it,” he said, “that now I go back over some of those sequences and I can’t figure out what I could have meant.”

On the desk, there was a rudimentary rocket made from one of those pencillike erasers with coiled paper wrappers that you unzip to expose the rubber. It stood on a base twisted out of a paper clip. The wrapper had been pulled up into a cone from which a needle protruded. I touched the needle with the tip of my finger and it fell into the cone. Tom frowned, cursed and spent at least a half hour tickling the needle back out again. As soon as he got it right and leaned back, I pushed it back in again. He put his face in his hands and almost wept. The grass was said to be Acapulco gold. It was strong and beautiful. The day was misty soft—cloudy water-color weather. We drove down the coast past a couple of towns to see an abandoned baroque hotel, something out of Bergman, but with a grand tattered Colonial flavor. As twilight thickened and condensed into liquid darkness, we returned to Manhattan Beach in relentlessly gathering fog. At night, we went down to the beach. The fog was so dense that the streetlights on The Strand disappeared a few yards’ walk toward the sea. Enveloped in opal-gray night we floated one another’s view, dancing down to the water. Only the foaming edge of the waves was visible, and even that was perceived mostly as a blurred lapping sound. We were alone on the empty margin of existence, walking the scant line between nowhere and nothing.

Too stoned to risk driving back to Laurel Canyon in the grainy fog, Chrissie and I slept the night in Tom’s dank bedroom while he made do on his studio couch in the living room. The head of the bed sat in a low notch of damp painted concrete formed by the floor of the room above. The room was a cave.

In the morning, there was sunshine. As we sat in the kitchen, Tom said, “Do you believe in ESP? Strange things keep happening to me. One day I was sitting in here and the side of my head came off, opening into Candida’s office, which I have never seen. She was talking on the telephone. Later, I spoke to her about it and told her what her office looked like. I had it all exactly right.

“You know the W.A.S.T.E. horn in The Crying of Lot 49? The symbol of the secret message service? Every weirdo in the world is on my wave length. You cannot understand the kind of letters I get. Someone wrote to tell me that the very same horn was the symbol of a private mail system in medieval times. I checked it out at the library. It’s true. But I made it up myself before the book was ever published, before I ever got that letter.”

When Chrissie and I got back home, there was a message for me to call a number in New York. It was the publisher of a new magazine for young people. He wanted me to go East and be editor. We left soon afterward without seeing Tom again. Less than a year later, depressed and whipped, I went back again to Los Angeles. We stayed in the Ramada Inn on Sunset Strip. Pynchon came bouncing into our room with a pound of excellent grass, the kind they called ice pack, and a chunk of violent hash. He was wearing a black-velvet cape. There was a mysterious undertone to his enthusiasm.

“What are you always so afraid of?” I asked him. “Don’t you understand that what you have written will get you out of almost anything you might get yourself into?”

There was no answer, but looking into his face, I could see his thought as plainly as if he had spoken out loud.

“You think that it is what you have they written that will want to get you for,” I said.

A few days later, on February 4, 1968, just before I was to leave for my brother’s birthday party, which was to be held on a big boat moored off San Pedro (James Gould Cozzens fans, note well), I slipped and fell and broke my hip. Tom had been invited to the party and, in fact, did show up, striking an acquaintance with Susan, a friend of Chrissie’s from San Marino. Susan has red hair and is breath-takingly beautiful, with the voluptuous body of a showgirl. Like Chrissie, she is much brighter than she looks, but if Chrissie plays the Dragon Lady, Susan plays Gracie Allen. The children of San Marino, one of the headquarters of The John Birch Society, are careful to avoid open displays of subversive intellect. Susan once came to the shattering realization while strolling on a concrete sidewalk that none of the squares was true, that, indeed, there were no true perfect squares to be found anywhere in reality. She was overcome by tears, then by nameless dread. A psychiatrist in San Marino diagnosed her a paranoid schizophrenic and prescribed shock treatment and apparently was going to administer it on the spot. Now really in hysterics, she called her father, who very sensibly countermanded the doctor’s orders and calmed his child himself. Since then, Susan has been very careful in guarding her emotions, to the point where she sometimes seems stupid and cold. It is a pose.

Evidently, Tom saw through her mask, for the two went off and lived together for a long time. They came to visit me in the hospital and later at home, too. The last evening they were there, Michael Vosse showed up. He had some tarry black ganja, which he said had been grown high in the mountains by natives who beat the plants with whips woven of silver thorns to make them produce more resin. We smoked the grass. It was indescribably intense. The pain of my broken hip expanded to fill the room. I found myself unable to stand Michael’s presence in the room and, after much reflective delay, finally asked him to leave. Alone with Chrissie and Susan and Tom, I felt some relief, but now the smell of the kitchen garbage bothered me. Tom volunteered to take it out. Chrissie went off to show him the way. Susan and I lay back, unable to move. The mood turned overwhelmingly sexual. I wanted to make love to Susan, but I couldn’t speak, overcome by the feeling and the karmic implications, my thoughts racing toward certain inevitable conclusions. The door opened. It was Tom and Chrissie. A little while later, he and Susan left. I knew then that it would be a very long time, if ever, before I saw him again.

Do you believe in ESP? I believe in everything and nothing. There are certain moments when it is all clear. The future lies spread out against your skull in blazing agony. There is the meaning of paranoia: not insanity but truth, the end of all our precious privacies, not the dignity of confession but the crazed gibber of the drooling beast.

•

Chrissie and I went back to New York. My career went from modest turn to modest turn and, before long, PLAYBOY sent me to do a story on hippie communes in California. She went on ahead of me while I stayed and finished a story on Herman Kahn that was purchased but never published. It was more than a month before I was to see her again. I felt the drift of her voice as she wandered off the telephone one day. It was nearly her birthday. I went down to B. Altman and sent her an ounce of Le De Givenchy. The day before I left to join her, it came back in the mail.

When I finally did reach Chrissie in Berkeley, where I had an assignment from The New York Times Sunday Magazine to do a story on the Black Panther Convention of 1969, the drift was subtle but very real. She was on her way to somewhere else and there seemed to be nothing that I could do to moor her interest. It was the week of the first landing on the moon. How appropriate that it was July, month of Cancer, of her birthday. After the convention, we visited a commune out in the redwoods and lived there for something like a month. Then I went off to Taos with a photographer and had various experiences, prophetic dreams and insidious anxieties I will possibly detail in some other work. I saw very far and well and truly, made certain decisions and returned to my wife not afraid.

One day we went for a walk in the redwoods and I said, “Chrissie, I love you more than any woman I have ever known, as much as I love my own mother. Something is troubling you. I think that it will make you feel better if you tell me what it is.”

“I had an affair with Tom,” she answered.

There it was. I felt all the things you feel in those circumstances, but mostly a sense of karma. Karma is what you get for what you do. It is also a certain perspective of reality. The words are flimsy, but the fact is about as graceful as a faceful of shit. Once, a long time ago. I had an affair with another man’s wife. The correspondence between the two events is not quite as algebraic as you might think. The private affair of married persons is merely a fact of life. We are all one person, really, and what one of us experiences the other must necessarily experience. too. I should like to say that I was calm and noble when my turn in the barrel came. Unfortunately, that would be a lie. I do not like to lie. I define honesty, though, as the ability to admit that you lie. I will spare you my hysterics. They lasted long enough.

The ethics are rather clear. People are not property. The hysterics over, Chrissie and I went on to attempt to reconstruct our marriage. In the course of that work, there were many conversations about what went on between the two of them that I suppose ought to be considered privileged. For the sake of the historical record, however, I do want to share a few of them with you. He was a wonderful lover, sensitive and quick, with the ability to project a mood that turned the most ordinary surroundings into a scene out of a masterful film—the reeking industrial slum of Manhattan Beach would become as seen through the eye of Antonioni, for example. Still, she found him somewhat unworldly and bookish, easily astonished by her boldness. Once, out on the freeway, she told him that we had all gone naked at the commune. He professed to find that incredible and dared her to take off her blouse right there. She did. A passing truck hooted its horn in lewd applause. He loved her Shirley Temple impersonations—On the Good Ship Lollipop sung and danced like a kid at a birthday party. They talked about running away together. He promised to get a job. Well, at least to move out of the cave. On their way to do the right thing, to tell me the truth, he insisted on stopping to get a pizza to calm his stomach. Then they changed their minds, fearful of one of my outrageous tantrums.

There is more and maybe I will tell it another time. I have received no letters from Tom in a long time. What did I do wrong? And those other letters—whatever did become of them? Ask the Dahill Mayflower Moving and Storage Company of Brooklyn. They are the victims of my inability to hold on to anything, sold at auction during through the hospitals to replace my crippled hip with one of plastic said to be almost as good as the real thing. Most probably, the auctioneer never even knew the value of those sheets of faint-blue quadrillé. I miss having them, but I miss some other things more—the hipbone I was born with, an antique brass oil lamp with milk-glass shade in like-new condition purchased one sunburned summer afternoon in Elkhorn Junction, Nebraska, a gilded-wood schoolhouse pendulum dock that stopped working when my first marriage ended, a signed first edition of The Godfather with this inscription: “Dear Chrissie and Jules. You too can be rich and famous. See how easy it is. Mario.”

Additional Information

Source: Playboy, March 1977

Return to: Pynchon Articles

Main Pynchon Page: Spermatikos Logos

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com