Joyce Music – Albert: Flower of the Mountain

- At January 24, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

Flower of the Mountain

(1985; 16 min)

For soprano and orchestra

Sun’s Heat

(1989; 30 min)

For tenor and orchestra

In 1985 Stephen Albert set aside Finnegans Wake and turned to Ulysses for inspiration. The result was Flower of the Mountain, a 16-minute long song for soprano and orchestra with lyrics adopted from the last two pages of Molly’s famous soliloquy. Loosely inspired by the songs of Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss, Flower was first performed on 17 May 1986 at the 92nd Street Y in New York City, with Gerard Schwarz conducting the New York Chamber Orchestra and Lucy Shelton as soprano. Flower of the Mountain was a finalist for the 1987 Pulitzer Prize in music.

A few years later Albert finished Sun’s Heat, a 30-minute piece for tenor and orchestra, with text drawn from Leopold Bloom’s recollection of the same events as Molly recalls in “Penelope.” Originally entitled Those Girls, Those Girls, Those Seaside Girls, the song was premièred on 27 April 1990, with Christopher Kendall conducting and David Gordon as tenor.

While either piece may be performed individually, taken together they form the two-part Distant Hills. Versions exist for both chamber and full orchestras. Unfortunately, no commercial recording of Sun’s Heat currently exists, so Flower of the Mountain remains the most popular of the two.

In conversation, Stephen Albert often referred to Flower of the Mountain not as a song, but an aria. It’s a prettier word and a more apt description; but this “aria” is more late-period Wagner than Verdi or Puccini. It begins with a mysterious prelude, sensuous and dreamy, the woodwinds undulating above dark, rolling strings and dampened piano. A sense of unresolved tension creates a feeling of longing, a bittersweet flavor that prevents the lush music from descending into sentimentality. This expectancy is fulfilled three-and-a-half minutes into the prelude, when a tremor thrills across the violins. The soprano finally arrives, her desire to have the “whole place swimming in roses” lifted on a glorious pean of horns. (The score marks her entrance to be sung “with radiance,” a delightfully Albertian notation.)

Lasting nearly thirteen minutes, the body of the aria develops with a blissful languor, the music rising and falling with Molly’s mood. As with Joyce’s original passage, the word yes and its repetitions act as a structural motif, a rhythmic engine accelerating the soliloquy towards its rapturous conclusion. Soon the glass-shattering notes begin appearing: a “yes” trilled high above the mountain flowers, Bloom’s heart “going like mad.” As Flower surges towards its ecstatic crescendo, the soprano doesn’t rise above the music, she is consumed, a passionate Liebestod that leaves the listener in tears. It’s that good—and one more reason to lament Albert’s tragic passing.

Liner Notes from the Nonesuch CD

Liner notes written by Joseph Horowitz:

Flower of the Mountain, dedicated to Lucy Shelton and Gerard Schwartz, is the fourth of Stephen Albert’s works inspired by James Joyce, the previous three being To Wake the Dead, TreeStone, and the Pulitzer Prize-winning RiverRun. The text is excerpted from Molly Bloom’s soliloquy from Ulysses: Molly Bloom lies awake in bed. Her husband, Leopold, is asleep beside her (albeit unorthodoxly positioned, his head at her feet). Her stream of consciousness ranges from making breakfast and shopping for clothes to blithe ruminations on family, religion, love. Two men dominate the dramatis personae of her unspoken monologue: her ill-nammed lover, “Blazes” Boylan, and her aging husband, a subject of irritation and, in snatches, grudging affection. Approaching slumber smooths and softens the drift of Molly’s thoughts. Finally, she fastens on a memory: lying with Bloom on the Hill of Howth 16 years ago, when he asked her to marry him and she said yes. Then she falls asleep.

Stephen Albert has set portions of this final, rapturous episode of Molly’s 25,000-word soliloquy: her reminiscence of the day she and Bloom decided to marry.

Flower of the Mountain was premiered on May 17, 1986 by Lucy Shelton and Gerard Schwartz with the Y Chamber Symphony (Now the New York Chamber Symphony of 92nd Street Y.)

Excerpts from “Stephen Albert in Conversation with Christopher Kendall” (1987)

Christopher Kendall: In performing and recording Into Eclipse, I’ve been struck by the complexity of its emotional texture. Since I find the music evoking the unsettling atmosphere of the Oedipus story in broad strokes rather than word for word, my response is to the music itself and not so much the text. From a purely musical point of view, what have you done to create such a feeling of conflict and intensity?

Stephen Albert: When I wrote Into Eclipse I was trying to merge seemingly disparate ideas, trying to create an unexpected sense of tension. Things that you would not ordinarily feel correspond stylistically or belong the same movement or musical phrase were brought together very rapidly. Sometimes, two bars of a sharply defined motivic or harmonic identity were merged suddenly with five bars of a contrasting nature. Layering these ideas, one on top of another, produced a similar result. It’s really like being beset by the unexpected, emotionally, while paradoxically using very familiar materials. Unpredictability and volatility are two of the ways in which, I think, music can produce an emotional response, and even a sense or depth in the listener, if the harmonic plan makes sense. The challenge is in finding way to use such disparities so that they seem musically inevitable.

CK: Did you use the same approach in Flower of the Mountain?

SA: That work was a little different. I think I tried to internalize this principle of the unexpected, make it a bit more subtle—to create longer lines, longer passages of stabilized feeling because Molly Bloom’s text had more constancy, more flow than the Oedipus text. The use of musical disparities and contrasts is much more discreet because of the more unified nature of the part of her monologue that I set.

CK: In spite of the really startling contrast between these two texts, I detect a common denominator, something that makes them both congenial to you.

SA: I think so. To begin with, I had a powerful, instinctual, response to both these texts. In retrospect, it seems to me that in these pieces we’re dealing with two individuals, Oedipus and Molly Bloom, who are experiencing a crucial life situation in which their use of memory is deeply affecting. The last two pages of Molly’s monologue, the part I use for her aria, are a specific kind of memory, a momentarily redeeming memory. The final aria of Into Eclipse is also a kind of redeeming moment in which Oedipus has finally found peace, and thinks about the irony of the terrible course or action he had to take to achieve that peace. But he has peace nevertheless, and so does Molly.

CK: The texts that you’re drawn to, and your Musical treatment would suggest to many listeners that you fit into a category that’s become something of a buzz-word these days: “‘Neo-Romanticism.” Do you consider yourself a Neo-Romantic composer?

SA: I believe my work is emotional and that it sounds “tonal.” It others want to label that sort of music Neo-Romantic who can stop them? But I suspect the term is misleading It implies that Romanticism disappeared a long time ago- at the end of the nineteenth century-and is only now making a nostalgic comeback in a new guise with all the old suppositions Intact.

CK: Did Romantic practice disappear in the twentieth century?

SA: I believe there were always two great traditions moving side by side in apparent opposition during the first half of the twentieth century, the Romantic and the Modernist. After all, on the Romantic side of the ledger, there are Mahler, Sibelius, Rachmaninov, Puccini, large portions of Prokofiev’s output, and Richard Strauss who, in 1948—the same year as Boulez’s Second Piano Sonata and a year after Schoenberg’s Survivor from Warsaw—wrote his Four Last Songs. From my point of view, the Romantic or affective impulse did not die sometime in the distant past. Nor, for that matter, did Classicism end with Mozart and Haydn.

Adapted from Stephen Albert’s Overtones Interview (1988)

Stephen Albert: I feel towards Ulysses the way I feel towards a piece of twentieth century poetry. It has the speech rhythms I love, it has the imagery that I love, it achieves its result through emotional indirection. Underneath it all, going back to Portrait of an Artist, I see a man of enormous sentimentality, almost like Irish blather. And at the same time I see this incredible pilot device guiding him down a twentieth century road, in which he felt that the way to obscure this, to fracture this, to create a distorted view of this sentimentality—almost to disguise his tracks—was to create this language, this almost delirious atmosphere, which is at the same time off-putting and very compelling to me as an artist. I find that I can re-inject back some of this sentiment, some of this emotion, that has been obscured by language. But at the same time the language itself, at its best, is so beautiful that it lends itself to being sung very well.

Text

Flower of the Mountain

I love flowers

Id love to have the whole place

swimming in roses

God of heaven

theres nothing like nature

the wild mountains then the sea

and the waves rushing

even out of ditches

primroses and violets

nature it is

the sun shines for you he said

the day we were lying among the rhododendrons

the day I got him to propose to me

yes first I gave him a bit of seedcake

out of my mouth

and it was leap year like now

sixteen years ago

my God after that long kiss

I near lost my breath

yes

he said I was a flower of the mountain

yes

so we are flowers all a womans body

yes

that was one true thing he said in his life

and the sun shines for you today (etc)

yes

and that was why I liked him

because I saw he understood or felt

what a woman is

O that awful deepdown torrent

O and the seas

and the sea crimson

sometimes like fire

and the glorious sunsets

and the fig trees in the Alameda gardens

yes

and rosegardens (and the) jessamine

and geraniums and cactuses (etc)

and Gibraltar as a girl

where I was a flower of the mountain

yes

when I put the rose in my hair

or shall I wear a red

yes

and how he kissed me under the Moorish wall

and I thought

well as well him as another

and then I asked with my eyes

to ask again

yes

and then he asked me

would I

yes

to say

yes

my mountain flower

and first I put my arms around him

yes

and drew him down to me

so he could feel my breasts

all perfume

and his heart was going like mad and

yes

I will

yes

Sun’s Heat

Those girls, those girls, etc., those lovely seaside girls.

Sharp as needles they are.

Eyes all over them.

Longing to get the fright of their lives,

Those girls, those lovely seaside girls.

Allow me to introduce my.

Have their own secrets.

Those girls, those girls, those lovely seaside girls.

Chaps that would go to the dogs if some woman didn’t take them in hand.

Wait.

Hm Hm Yes—that’s her perfume.

What is it? Heliotrope?

Know her smell in a thousand.

Bath water, too.

Reminds me of strawberries, and cream.

Hyacinth perfume made of oil or ether or something.

Muscrat. That’s her perfume.

Dogs at each other behind.

How do you sniff?

Hm, Hm. Animals go by that

Yes now,

Dogs at each other behind,

Good evening. Evening.

Yes now, look at it that way we’re the same.

Just close my eyes a moment won’t sleep though.

Half dream. She kissed me.

Half dream. My youth.

It’s the blood of the south.

Moorish.

Also the form. The figure.

Just close my eyes, half dream,

She kissed me, kissed me, kissed me.

Sun’s heat it is seems to a secret touch telling me memory.

Below us bay sleeping sky,

No sound

The sky.

The bay purple fields of under sea…buried cities.

Pillowed on my coat she had her hair

Earwigs in the heather scrub,

my hand under her nape, you’ll toss me all.

O wonder! Softly she gave me in my mouth seed-cake warm and chewed

Joy: I ate it: Joy.

Young life her lips that gave me pouting.

Flowers her eyes were, take me, willing eyes.

All yielding she tossed my hair,

Kissed, she kissed me.

Willing eyes all yielding.

Me. And me now.

Dew falling. The year returns.

Ye crags and peaks I’m with you once again.

The distant hills seem.

Where we.

The rhododendrons

All that old hill has seen

All changed forgotten.

And the distant hills seem coming nigh.

A star I see

Were those night clouds there all the time?

No. Wait.

Trees are they?

Mirage.

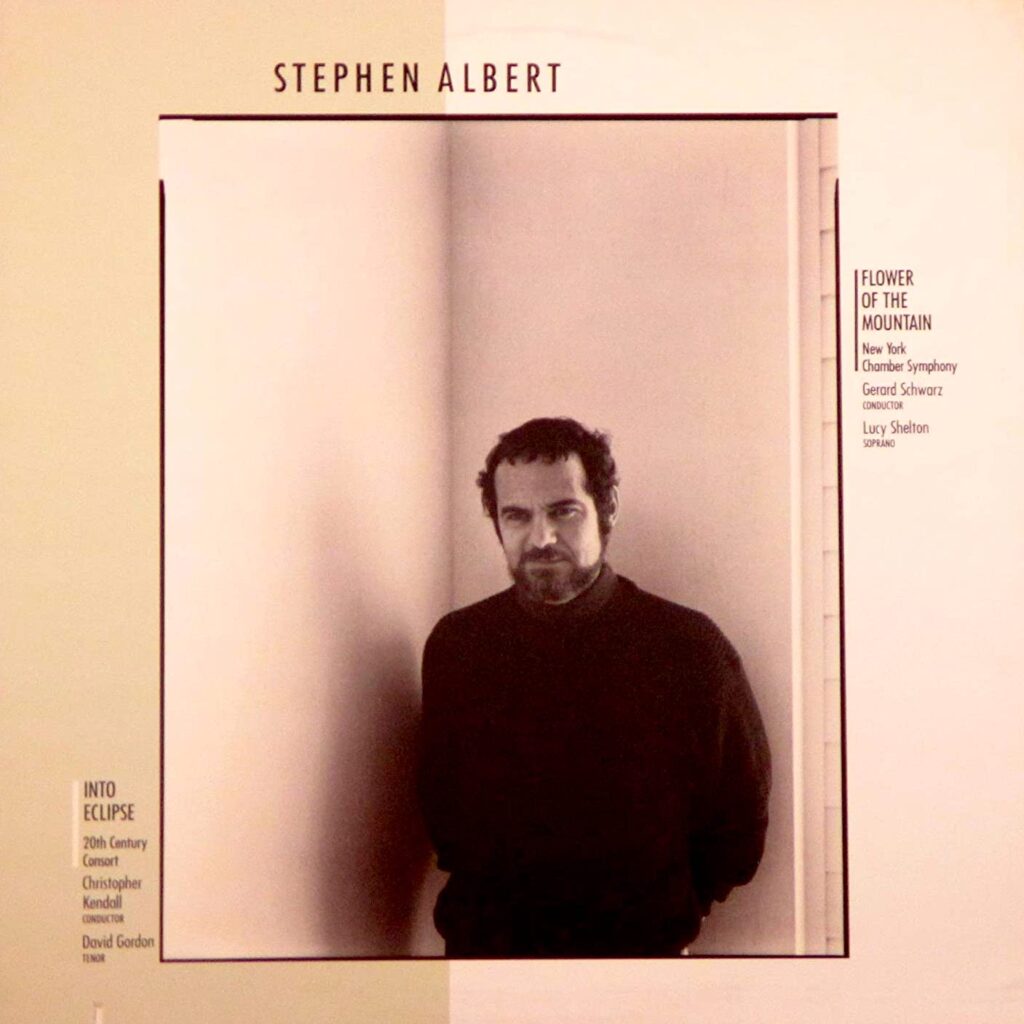

Recordings

Albert: Flower of the Mountain

Conductor: Gerard Schwarz

Musicians: New York Chamber Symphony

Soprano: Lucy Shelton

LP: Flower of the Mountain & Into Eclipse. Elektra Nonesuch 9-79153-1 (1987)

CD: Flower of the Mountain & Into Eclipse. Elektra Nonesuch 9-79153-2 (1987)

Purchase: CD [Amazon]

Online: YouTube

There is only one commercial recording of Flower of the Mountain available, featuring Gerard Schwarz conducting the New York Chamber Symphony with Lucy Shelton singing. It was released on LP and CD in 1987 by Elektra Nonesuch. Sadly deleted, this album pairs Flower of the Mountain with Albert’s stirring Into Eclipse, based on Ted Hughes’ translation of Seneca’s Oedipus. Lucy Shelton has sung every one of Albert’s soprano parts since To Wake the Dead, and her performance on this recording represents the capstone of their artistic partnership. Her voice is wonderfully operatic, embracing the drama of the text, yet finely attuned to its subtle shifts in mood. Shelton finds a myriad of fresh ways to sing “yes,” all of which remain sensitive to their individual meanings in the text—a hushed prayer, a triumphant affirmation, an urgent confirmation between verses. No stranger to Albert’s music himself, Gerard Schwarz brings the New York Chamber Symphony to life. The French horns and piano are particularly effective, and the way Shelton’s final “yes” trails off into the slow breathing of horns and woodwinds is sublime. Highly recommended.

Additional Information

Flower of the Mountain Score

The score of Flower of the Mountain is available to peruse at Issuu.

Stephen Albert “Overtones” Interview

Overtones, 1988. A very engaging and informative interview with Stephen Albert, who discusses his relationship to James Joyce, his compositional process, and his thoughts on modern music.

Stephen Albert Interview with Bruce Duffie

WNIB, 9 December 1990. The transcript of a telephone interview conducted with Stephen Albert.

Stephen Albert: Other Joyce-Related Works

Stephen Albert Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Stephen Albert profile.

To Wake the Dead (1978)

This remarkable song cycle is subtitled, “Six Sentimental Songs and an Interlude after Finnegans Wake.”

TreeStone (1983)

Albert’s second song cycle inspired by Finnegans Wake, TreeStone is loosely based on the legend of Tristan and Iseult.

Symphony RiverRun (1983)

The gloriously dramatic Symphony RiverRun expands on Albert’s previous Wake-inspired material. It won the 1985 Pulitzer Prize in music.

Ecce Puer (1992)

A setting of Joyce’s final poem for soprano.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 16 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com