Joyce Music – Albert: To Wake the Dead

- At January 24, 2022

- By Great Quail

- In Joyce

0

0

I used “Finnegans Wake” more or less as a reference work, the way other composers might use the Bible, finding certain passages in it that lend to musical treatment of a direct sort, such as actual song settings, or a more indirect sort, such as my symphony. The symphony in not really a programmatic work in the accepted sense: it represents my response to a Joycean stimulus, but that response is not the type that involves an attempt at direct imagery.

—Stephen Albert

To Wake the Dead

(1978)

1. How it ends

2. Riverrun (ballad of Persse O’Reilly)

3. Pray your prayers

4. Instruments

5. Forget, Remember

6. Sod’s brood, Mr. Finn

7. Passing Out

Stephen Albert’s first composition inspired by James Joyce, To Wake the Dead is subtitled “Six Sentimental Songs and an Interlude after Finnegans Wake.” It’s scored for chamber ensemble and soprano, with lyrics adapted from Joyce’s text.

A truly magnificent piece of music, To Wake the Dead is one of my favorite song cycles, perhaps the best example of its type since Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs, a work that Albert has praised extensively. Albert’s suite may promise “sentimental” songs, but there’s a cheeky irony to the subtitle. While the songs revolve around sentimental themes such as love and loss, the language remains entirely Wakean, the Joycean wordplay casting a dreamlike spell over “Love’s Old Sweet Song.” The music reflects the mercurial ambiguity of the Wake’s language, its melodies and rhythms shifting and transforming with graceful liquidity. As with certain passages from Wagner, Debussy, and Mahler, Albert’s music possesses a sense of mystery that’s difficult to explain, suffused with the delicate ache of unresolved tensions and sensitive to the strange beauty of the new. And yet, there’s something hauntingly familiar about Albert’s music—to use his own description of Joyce’s writing, a “convoluted nostalgia.” It’s a wonderful language to express the mythic dreaming of the Wake.

Just like Finnegans Wake itself, we begin with “How it ends.” Opening with the plaintive sound of a cello stirring to life, the song takes shape slowly, a morning landscape emerging from the predawn gloom. Beautiful and quietly dramatic, this is the music of springtime: querulous rivulets of violin, tumbling eddies of piano, the leafy speafing of woodwinds like blossoming buds. The instruments fade to silence as the soprano enters: “Oaks of ald lie in peat / Elms leap where askes lay…” The melody is amorphous and mysterious, like fog rising from the river. As the instruments return, the soprano swirls around them, gliding with the cello here, falling in step with the piano there, finally lifting away and out of range.

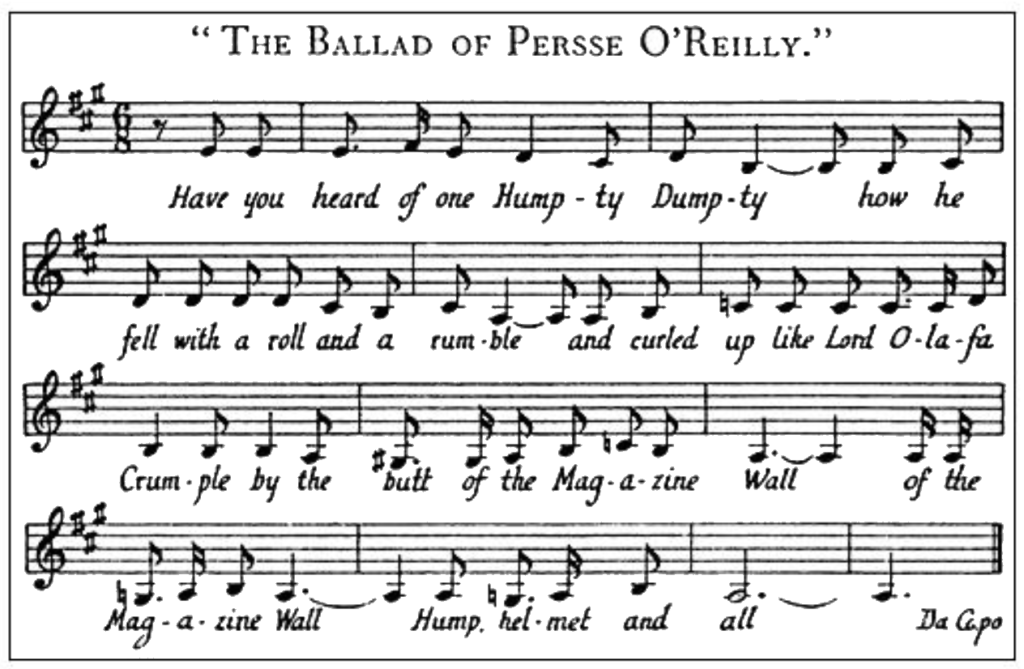

Near the conclusion of “How it ends” we catch a fragment of melody, a lilting figure muttered on the violin like a half-remembered song. A few seconds into the next song we realize this wasn’t a memory, but foreshadowing. As the subtitle of “Riverrun” suggests, the melody is “The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly,” and has the distinction of being inscribed in Finnegans Wake as actual sheet music. Adapted from an old Irish tune called “Mush Mush,” the song narrates the fall of H.C. Earwicker, the Wake’s recurring protagonist, relating him to—among others—Humpty Dumpty.

Albert adapts the first two stanzas of Joyce’s song, placing the melody high in the soprano’s range, where it bounces and skips with eggshell fragility above a disjointed piano. The same melody will appear a few years later in Albert’s Symphony RiverRun, notated “like a children’s music box.” The conclusion of “Riverrun” further anticipates the symphony, its childlike cadences transformed into a staggering march not unlike a “boozy wake.”

Next up is “Prayer your prayers.” Like so many bedtime prayers and cheerfully sadistic lullabies, the lyrics openly court some kind of nocturnal disaster, a combination of “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep” and the Protestant’s supplication from Monty Python and the Meaning of Life. As the soprano beseeches the “Loud” to spare her children to “ming no merder,” the violin offers a yearning melody, entwining her prayer with “laughter low.” The ending is a sublime moment of doleful timidity: “Say your prayers Timothy,” hushed over bass clarinet.

The promised interlude lets the orchestra cut loose, a two-minute torrent of swirling music. After passing through these whitewater rapids, we return to tranquility. “Forget, Remember” opens with an enigmatic melody played on bass flute. Soon the piano enters, the pianist plucking the exposed strings, pizzicato shimmering above the dreamy haze. A cello and bass clarinet accompany the soprano, who sings thready and low, as befitting the dreamy subject. As the “soft morning” continues, the melody brightens, almost imperceptibly, passed from bass clarinet to clarinet, cello to violin, and bass flute to flute. Contrary to its orchestral companions, the piano descends down its register. The song ends with a tremor of excitement, a rhythmic figure played on low keys with the pianist’s palm damping the strings.

The mood shifts violently with the operatic fireworks of “Sod’s Brood, Mr. Finn.” Driven by a martial rhythm, the song careens through a rollicking landscape marked by bursts of pizzicato, frantic solos, and clusters of dissonance. These orchestral combatants come together during the climax, the soprano’s “Ho Ho Ho Ho” soaring above the clash like a barrage of rockets.

To Wake the Dead concludes with “Passing Out.” Seven minutes in length, it’s the longest song, and recapitulates many of the suite’s melodies and lyrical phrases. It’s also wonderfully dramatic, divided into three thematic sections and concluding with the final sentence of Finnegans Wake.

The opening returns to the themes of remembrance and forgetting, the music soft and longing. Occasionally an abbreviated figure is heard on the piano, a dramatic sequence of notes like a truncated fanfare. A few years later, this fragment will return as the dramatic opening to Symphony RiverRun. Here, the music surges to a peak with the repetition of “my cold mad feary father.”

The middle sequence begins with “I rush only into your arms,” sung prayerfully above a harp of plucked piano strings. The “Persse O’Reilly” melody returns for a final bow, shaping the celebrated passage “so soft this morning ours.” Each verse ends with the word “Taddy,” breathed by the soprano at the bottom of her range. It’s a melancholy sequence, delicate and ghostly, one dream slipping into another.

This brings us to the closing passage, beginning with the lyric “First we pass through the grass.” Here, Albert has one final surprise in store: traditional harmonic and melodic structure. A genuinely “sentimental” gesture, this hymn-like passage feels transported from a Victorian drawing room—perhaps the Morkan sisters’ Dublin parlor? (There’s even a harmonium!) As the song winds to its final, broken sentence, the traditional structures unravel and the music dissolves into the plaintive mystery that marked the beginning of the suite. As the lace curtains fall away, we realize we’ve never left the riverside: “Away alone a last a loved along the—” Every fan of Finnegans Wake knows the next word. In the case of Albert, he voiced it with a symphony.

Liner Notes from the 1992 Delos CD

Liner notes written by Richard Freed:

Stephen Albert was born in New York on February 6, 1941.

From the beginning, Albert has pursued a truly independent course, not as a rebel or an “outsider,” but simply as a creative thinker who developed a personal outlook without regard for what may have been “in” or “out” in musical fashions, but with apparent concern for expression and communication. (Among the composers of the past whom he mentions as influential in his own work are Sibelius, who is generally undervalued today, as well as Brahms, Mahler and Stravinsky, who are certainly “in,” and, in Albert’s earlier years, Bartók and Ives.)

To Wake the Dead, composed 1977-1978, marked the beginning of Albert’s response to that [James Joyce] literary stimulus. The song cycle TreeStone was the second, RiverRun the third, and Flower of the Mountain, composed for Lucy Shelton in 1985, brought the total of his Joycean works to four. Since the motivation for the first three of these came from Finnegans Wake, and Flower of the Mountain is a setting of the final pages of Molly Bloom’s long soliloquy in Ulysses, it is surprising to have Albert tell us the A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man was the only work of Joyce’s he had read in its entirety when he composed most of these works. “I didn’t really read Finnegans Wake from beginning to end,” he says; “I used it more or less as a reference work, the way other composers might use the Bible, finding certain passages in it that lend to musical treatment of a direct sort, such as actual song settings, or a more indirect sort, such as my symphony. The symphony in not really a programmatic work in the accepted sense: it represents my response to a Joycean stimulus, but that response is not the type that involves an attempt at direct imagery.”

Albert is attracted, he says, to “the very musical rhythm of Joyce’s language; among 20th-century poets, only T.S. Eliot and perhaps Yeats strike me as being more musical in that respect. The flashes of imagery are marvelous, and there is that convoluted nostalgia—for under all his artful disguises and arcane language one finds a basic Irish sentiment which I for one like so much. In his work I discovered what I regard as a foreign language—a language enormously suggestive of English, and of course directly related to English, but essentially a foreign language. Through this invented language he has been able to elusively chronicle man’s endurance of tragedy and the whole human comedy . . . Finnegans Wake does not produce literal or direct images for me, but works in terms of generalized suggestions and impressions. This stimulus produces a sort of mental atmosphere that provides for me an escape from contemporary America—in much the same way, I suppose, that the theological stimuli to which Bach responded provided him an escape from the realities of early 18th-century Leipzig.”

To Wake the Dead, Albert’s earliest response to the stimulus of Finnegans Wake, was given its premiere in New York on March 21, 1979, by Pro Musica Moderna, which group recorded it at that time; the performance by the Twentieth Century Consort on the present disc was recorded 18 months later and was originally issued on LP by the Smithsonian Institution in 1982. In addition to the soprano solo, the score, subtitles “Six Sentimental Songs and an Interlude after Finnegans Wake,” calls for flute (doubling alto flute and piccolo), clarinet (doubling bass clarinet), violin (doubling viola), cello, piano, and harmonium.

Working with Joyce’s actual words dictated a less sumptuous approach than that of the symphony. The colors in this work are somewhat sharper, the textures relatively rougher, the themes more angular; but within this more restricted range there is a remarkable variety, enhancing that of the expressive content of the texts. The six songs are truly songful in their treatment of the basic human concerns which the symphony treats more expansively, and they constitute a true “cycle,” held together by subtle musical links as well as their common literary source—and, indeed, a distillation of much of that source’s essence. In an earlier note on this work, Kenneth Slowik suggested that a “useful summary of its major themes,” is provided in these lines from Joseph Campbell’s famous study A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake:

Tim Finnegan of the old vaudeville song is an Irish sod carrier who gets drunk, falls off a ladder, and is apparently killed. His friends hold a death watch over his coffin; during the festivities someone splashes him with whiskey, at which Finnegan comes to life again and joins the general dance . . Finnegan’s fall from the ladder is Lucifer’s fall, Adam’s fall, the setting sun that will rise again, the fall of Rome, a Wall Street crash . . . It is Humpty Dumpty’s fall and the fall of Newton’s apple. And it is every man’s daily recurring fall from grace . . . By Finn’s coming again (Finn-again)—in other words, by the reappearance of the hero—. . . Strength and hope are provided for mankind.

The brief instrumental interlude placed in the center of the cycle exploits the color potentials of the ensemble in a concise and energetic gesture which serves as a sort of summing-up and an ingathering of strength for the rest of the tale, without allowing momentum—or attention—to slacken.

Text

To Wake the Dead

1. How it ends

Oaks of ald lie in peat

Elms leap where askes lay

Phall if you but will, rise you must

In the nite and at the fading.

What has gone,

How it ends,

Today’s truth

Tomorrow’s trend.

Forget remember

The fading of the stars

Forget…Begin to forget it.

2. Riverrun (ballad of Persse O’Reilly)

Have you heard of one Humpty Dumpty

How he fell with a roll and rumble

And curled up like Lord Olafa Crumple

By the butt of the Magazine Wall

Of the Magazine Wall

Hump helmet and all.

He was once our king of the castle

Now he’s knocked about like a rotten old parsnip

And from Green Street he’ll be sent by

the order of his worship

To the penal jail of Mount Joy

Jail him and Joy.

Have you heard the one Humpty Dumpty

How he…

—Riverrun, riverrun

Past Eve and Adam’s

From swerve of shore to

bend of bay—

…How he fell with a roll and a rumble

And not all the kings’s men nor his horses

Will resurrect his corpus

For their’s no true spell in Connacht or Hell

That’s able to raise a Cain.

—Riverrun, riverrun—

3. Pray your prayers

Loud hear us

Loud graciously hear us

O Loud hear the wee beseech of thees

We beseech of these of each of thy unlitten ones.

Grant sleep

That they take no chill

That they ming no merder, no chill,

Grant sleep in hour’s time.

Loud heap miseries upon us

Yet entwine our arts entwine our

arts with laughter low.

Loud hear us

Hear the we beseech of thees.

Say your prayers Timothy.

4. Instruments (Voice Tacet)

5. Forget, Remember

Rush, my only into your arms

So soft this morning ours

Carry me along

I rush my only into your arms.

What has gone

How it ends

Today’s truth

Tomorrow’s trend.

Forget

Remember.

6. Sod’s brood, Mr. Finn

What clashes here of wills

Sod’s brood be me fear.

Arms apeal

With larms appalling

Killy Kill Killy a-toll a-toll.

What clashes here of wills

Sod’s brood

He points the death bone…

Of their fear they broke

They ate wind

They fled

Of their fear they broke

Where they ate there they fled

Of their fear they fled

They broke away.

O my shining stars and body.

Hold to now

Win out ye devil, ye.

…and the quick are still

He lifts the life wand

And the dumb speak.

Ho Ho Ho Ho Mister Finn

You’re goin’ to be Mr. Finnagain

Come day morn and O your vine

Send-days eve and, ah, your vinegar.

Ha Ha Ha Ha Mister Fun

Your goin’ to fined again.

7. Passing Out

Loonely in me loonelyness

For all their faults I am passing out,

O bitter ending.

I’ll slip away before they’re up

They’ll never see nor know nor miss me.

And it’s old, it’s sad and weary

I’ll go back to you

My cold father

My cold mad feary father

Back to you.

I rush my only into your arms.

So soft this morning ours

—Yes

Carry me along

—Taddy

Like you done through the toy fair

—Taddy

The toy fair

—Taddy

First we pass through grass

behush the bush to.

To whish a gull

Gulls

Far far crys

Coming far

End here

Us then Finnagain

Take, bussoftlhe memormee

Till thou sends the

Away alone

a last a loved

along the

Recordings

To Wake the Dead is available on two commercial recordings. Considering they’re separated by only eighteen months, they offer surprisingly different interpretations. The Fussell/Allen recording approaches the songs as avant-garde pieces, while the Kendall/Shelton recording offers a more traditional, melodic take. Both are worth a listen; but unfortunately, both suffer from imperfect production.

|

|

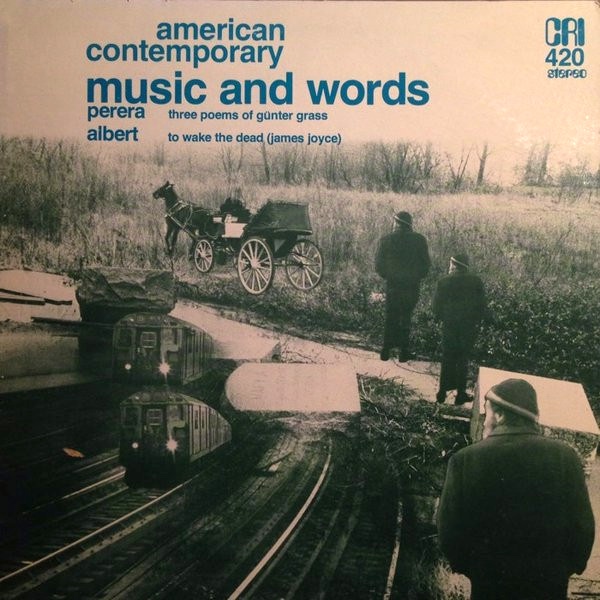

Albert: To Wake the Dead (1980)

Conductor: Charles Fussell

Musicians: Pro Musica Moderna

Soprano: Sheila Marie Allen

LP: Music and Words. CRI SD 420 (1980)

Digital: Perera/Albert: Vocal Works. New World NWCRL 420 (2017)

Purchase: LP [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

This album contains the first performance of To Wake the Dead, recorded during its New York première on 21 March 1979. The recording was first released on LP by CRI in 1980, paired with Ronald Perera’s “Three Poems of Günter Grass” on an LP entitled Music and Words. In 2017, New World digitally reissued the recording as Perera/Albert: Vocal Works. The Fussell recording is more sharply defined than the 1982 Kendall/Shelton version. While the dynamics are satisfyingly crisp, the piano seems over-miked and dominates the mix. Sheila Marie Allen’s voice has a harder edge than Lucy Shelton’s, and she brings more drama to the lyrics—her sneering delivery of “By the butt of the Magazine Wall” wouldn’t sound out of place in a production of Berg’s Lulu.

|

|

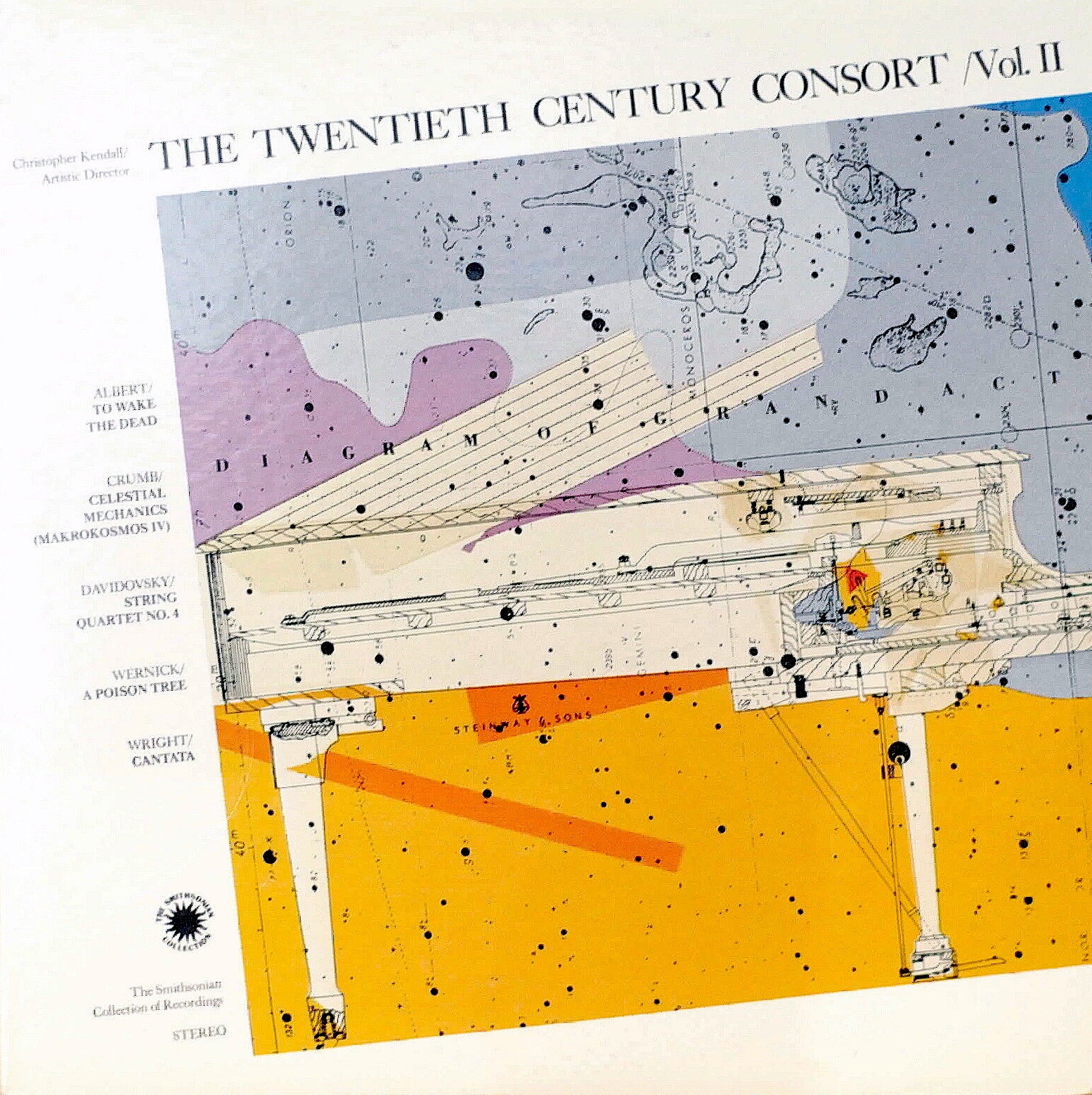

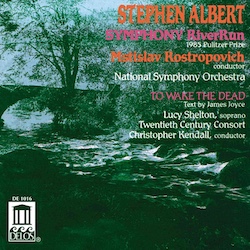

Albert: To Wake the Dead (1982)

Conductor: Christopher Kendall

Musicians: Twentieth Century Consort

Soprano: Lucy Shelton

LP: Twentieth Century Consort Vol. II. Smithsonian N 027 (1982)

CD: Symphony RiverRun; To Wake the Dead. Delos D/CD 1016 (1998)

Purchase: CD [Amazon], Digital [Presto Music]

The second recording of To Wake the Dead was made eighteen months after the first. In 1992, it was released on LP by the Smithsonian Collection of Recordings as part of a Twentieth Century Consort compilation. In 1998 Delos issued the recording on CD, paired with Mstislav Rostropovich’s masterful première of Albert’s Symphony RiverRun, recorded in 1987 at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Kendall’s version of To Wake the Dead is more lush and lyrical than the Fussell recording, even if the dynamics have a slightly muffled quality.

Online Video

The following excerpts and live performances are available on YouTube.

Albert: To Wake the Dead

Recorded on 9 October 2021 at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C.

Conductor: Christopher Kendall, 21st Century Consort

Soprano: Catherine Gardiner

It’s a shame this performance wasn’t recorded for commercial release, as it’s superior to both Fussell’s première and Kendall’s own recording with Lucy Shelton from 1982. Having lived with the piece for forty years, Kendall shows a remarkable mastery of the suite, highlighting each moment with grace and nuance. A bass flute has been added to the orchestration, and a second pianist stands ready to help with the various special effects. And best of all, Catherine Gardiner’s voice is superb! Warm and sensitive to detail, she proves a worthy successor to Lucy Shelton. Highly recommended!

Additional Information

Stephen Albert Interview

Overtones, 1988. A very engaging and informative interview with Stephen Albert, who discusses his relationship to James Joyce, his compositional process, and his thoughts on modern music.

Stephen Albert: Other Joyce-Related Works

Stephen Albert Main Page

Return to the Brazen Head’s Stephen Albert profile.

TreeStone (1983)

Albert’s second song cycle inspired by Finnegans Wake, TreeStone is loosely based on the legend of Tristan and Iseult.

Symphony RiverRun (1983)

The gloriously dramatic Symphony RiverRun expands on Albert’s previous Wake-inspired material. It won the 1985 Pulitzer Prize in music.

Flower of the Mountain/Sun’s Heat/Distant Hills (1985-1989)

Flower of the Mountain is based on Molly’s soliloquy in Ulysses. In 1989 Albert paired it with another Ulysses-inspired song, Sun’s Heat. Together they form a two-movement piece called Distant Hills.

Ecce Puer (1992)

A setting of Joyce’s final poem for soprano.

Author: Allen B. Ruch

Last Modified: 16 June 2024

Joyce Music Page: Bronze by Gold

Main Joyce Page: The Brazen Head

Contact: quail(at)shipwrecklibrary(dot)com